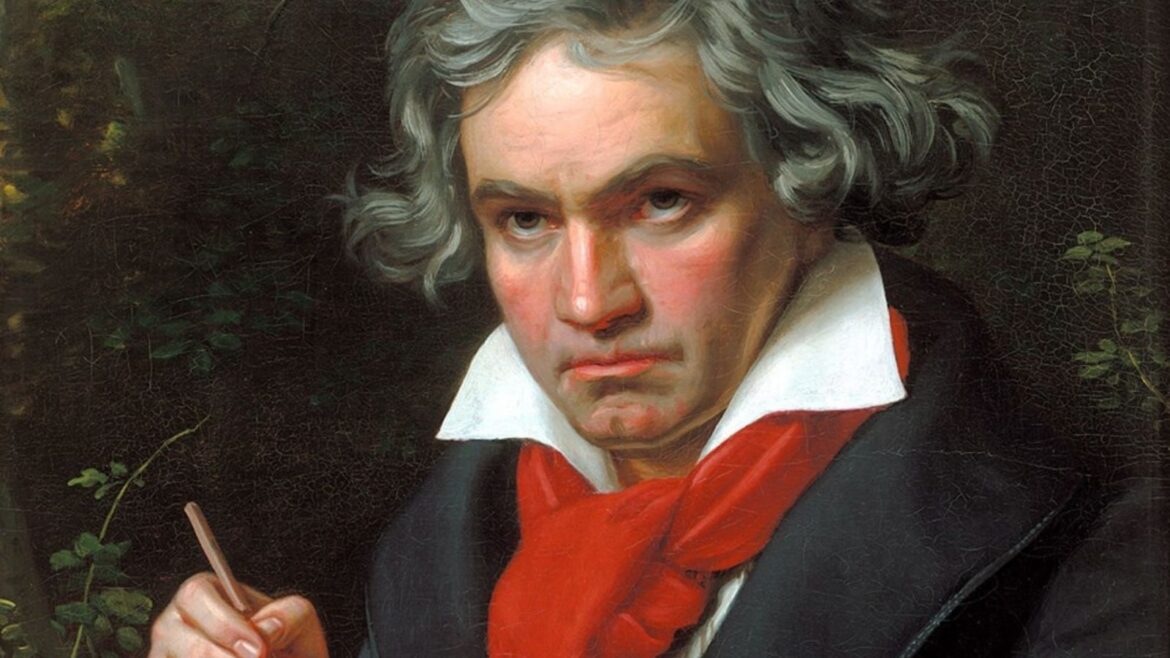

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers in the history of Western classical music. He was a revolutionary figure whose music transcended the boundaries of his era and laid the foundation for the Romantic movement in music. Beethoven’s life and work reflect a story of immense talent, personal struggle, and artistic triumph that continues to inspire audiences and musicians across the world.

Early Life and Background

Beethoven was born in Bonn, Germany, in December 1770, and baptized on December 17, which suggests he was likely born a day earlier. His family was of Flemish origin. His father, Johann van Beethoven, was a court musician and recognized Ludwig’s musical potential early on. He sought to turn his son into a prodigy like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, pushing young Beethoven into a strict regimen of music education.

By his teenage years, Beethoven was already a skilled pianist and organist. He studied with prominent local musicians and caught the attention of the Elector of Cologne, who sent him to Vienna, the musical capital of Europe, in 1792 to study under the renowned composer Joseph Haydn.

Vienna and Musical Development

Beethoven moved permanently to Vienna in his early twenties, and it became his home for the rest of his life. The city offered fertile ground for Beethoven’s talents, and he quickly gained a reputation as a virtuosic pianist, impressing aristocrats with his fiery performances and improvisational skills.

While studying under Haydn, Beethoven absorbed the Classical forms perfected by Haydn and Mozart but soon began to push boundaries. His early works, such as the First and Second Symphonies, display clear Classical structure, but they also reveal a unique voice—bold, dramatic, and emotionally charged.

His Piano Sonatas, such as the Pathétique Sonata (Op. 13) and Moonlight Sonata (Op. 27, No. 2), demonstrated a new depth of emotional expression and became instantly popular. He also composed string quartets, trios, and concertos that showed increasing mastery and innovation.

Struggles with Deafness

One of the most tragic aspects of Beethoven’s life was his progressive hearing loss, which began in his late twenties. For a musician, especially one as devoted to sound as Beethoven, this was a devastating blow. He tried to hide it at first, withdrawing from public performance and social gatherings. As the condition worsened, he began using ear trumpets and notebooks to communicate.

In 1802, he wrote the Heiligenstadt Testament, a letter to his brothers in which he confessed his despair and thoughts of suicide. However, he also declared a determination to live for his art. This marked a turning point in his life and work.

Despite his deafness, or perhaps because of it, Beethoven’s music became even more powerful, introspective, and transcendent. He began what musicologists call his “Middle Period”—sometimes referred to as his “Heroic Period.”

Heroic Period and Major Works

From 1803 to around 1812, Beethoven produced many of his most celebrated and groundbreaking compositions. He expanded the scale, ambition, and emotional depth of his works, challenging performers and listeners alike.

Key works from this period include:

- Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major (Eroica), Op. 55: Originally dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte, whom Beethoven admired as a symbol of liberty and revolution. When Napoleon declared himself emperor, Beethoven furiously scratched out the dedication. The Eroica symphony broke the mold of Classical symphonic structure and introduced an unprecedented dramatic scope.

- Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67: Perhaps the most famous symphony in history, it opens with the iconic four-note motif (“fate knocking at the door”). The symphony moves from darkness to triumph, mirroring Beethoven’s own struggles.

- Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major (Emperor), Op. 73: A majestic and virtuosic concerto that places the piano on an equal footing with the orchestra.

- Opera: Fidelio: Beethoven’s only opera, a story of love, courage, and freedom.

- Symphony No. 6 in F major (Pastoral), Op. 68: A serene and descriptive piece that celebrates nature and rural life.

This period also included major piano sonatas such as the Waldstein and Appassionata, and a set of Razumovsky string quartets.

Late Period and Musical Transcendence

By the 1810s, Beethoven’s hearing was nearly gone. He no longer performed publicly and became increasingly isolated. Yet, in this final phase of his life, often called the “Late Period”, he composed some of his most profound and spiritually elevated music.

These late works are characterized by innovation, complexity, and introspection. They often abandon traditional forms and incorporate elements of counterpoint, variation, and fugue.

Key late works include:

- Missa Solemnis in D major, Op. 123: A monumental setting of the Catholic Mass that Beethoven considered one of his greatest achievements.

- Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125: Known as the Choral Symphony, this was Beethoven’s final completed symphony. Its final movement, the “Ode to Joy,” based on Friedrich Schiller’s poem, celebrates universal brotherhood and remains one of the most iconic pieces of music ever written.

- Late String Quartets: Particularly Op. 130–135, these quartets puzzled audiences at the time with their complexity and intensity. Today, they are considered among the greatest achievements in chamber music.

- Piano Sonata No. 29 (Hammerklavier), Op. 106 and No. 32, Op. 111: These works explore vast emotional and structural territory and represent Beethoven’s visionary spirit.

Death and Legacy

Beethoven died on March 26, 1827, at the age of 56 after a long illness. His funeral in Vienna was attended by thousands, and his passing was mourned throughout Europe.

He left behind a body of work that fundamentally reshaped the possibilities of music. Beethoven bridged the Classical and Romantic eras, showing that music could express the deepest human emotions and philosophical ideas. He demonstrated that a composer’s personal voice could speak universally.

His influence is immeasurable:

- Romantic composers such as Brahms, Wagner, Schumann, and Liszt were deeply inspired by him.

- Modern and contemporary composers, including Mahler and Stravinsky, saw him as a foundational figure.

- The “Ode to Joy” melody was adopted as the anthem of the European Union.

- His music continues to be performed, studied, and revered globally.

Conclusion: The Eternal Voice of Humanity

Beethoven’s story is one of triumph over adversity. Deafness, isolation, and social difficulties could not silence his genius. In fact, they may have fueled his drive to create music that spoke to the deepest aspects of the human condition.

Whether through the stormy chords of the Appassionata, the joyful strains of the Ninth Symphony, or the sublime serenity of his late string quartets, Beethoven’s voice remains alive, urgent, and eternally relevant. He was not just a composer for his time—he was, and remains, a composer for all time.