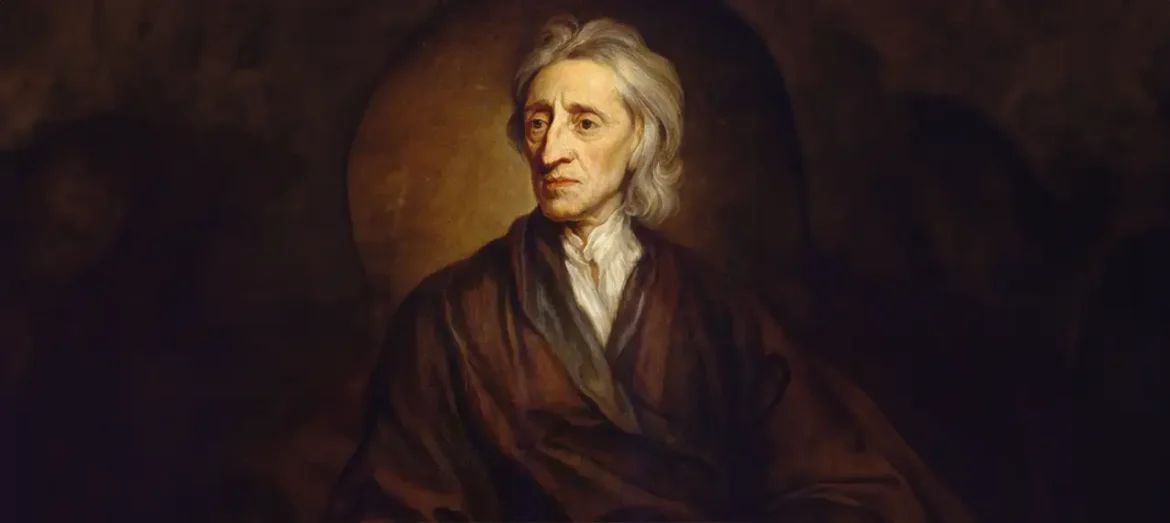

John Locke was an English philosopher and physician widely regarded as one of the most influential figures of the Enlightenment. His contributions to political philosophy, epistemology, education, and theology laid critical foundations for modern liberal democracies, scientific empiricism, and theories of the mind. Through works like Two Treatises of Government and An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Locke challenged absolutism, defended rights of individuals, and emphasized the central role of experience in human knowledge.

1. Early Life and Historical Context

John Locke was born on August 29, 1632, in Wrington, Somerset, England. He studied at Westminster School and later at Christ Church, Oxford, where he focused on classics, philosophy, and medicine. This academic environment exposed him to new scientific and philosophical ideas—particularly those of René Descartes, Robert Boyle, and Thomas Sydenham.

Locke lived through a tumultuous period of English history: the English Civil War, the execution of Charles I, the Restoration, and the Glorious Revolution of 1688. These events shaped Locke’s political theories, particularly his critiques of absolute monarchy and his arguments for religious tolerance, property rights, and government by consent.

2. Empiricism and the Blank Slate

In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), Locke rejects innate ideas, arguing instead that the mind at birth is a tabula rasa—a blank slate—to be filled through experience. Knowledge, he asserts, comes exclusively from:

- Sensation: direct sensory input (sight, sound, taste, etc.).

- Reflection: the mind reflecting upon its own operations (thinking, doubting, willing).

From simple ideas like “redness” and “sweetness,” the mind forms complex ideas (like “apple” or “justice”) by combining, comparing, and abstracting basic impressions.

Locke identified primary qualities (e.g., solidity, extension, motion), which are intrinsic to objects, and secondary qualities (e.g., color, taste), which are perceived subjectively through experience.

Locke’s empiricism greatly influenced scientific methodology and cognitive science, emphasizing observation, experimentation, and modesty in claims about what can be known.

3. Knowledge, Faith, and Reason

Locke distinguished between various kinds of knowledge:

- Intuitive knowledge: direct certainty (e.g., “I exist,” “white is not black”).

- Demonstrative knowledge: knowledge through logical proof (e.g., geometry).

- Sensitive knowledge: probable knowledge about the world (e.g., “The sun will rise tomorrow”).

He maintained that while reason is essential to knowledge, faith has its own realm and can operate without rigorous empirical proof. In The Reasonableness of Christianity (1695) and other letters, he argued for a rational basis of faith and promoted tolerance of different Christian sects.

4. Personal Identity and Consciousness

Locke is known for his psychological theory of identity. In Essay, he famously defines personal identity not in terms of substance—whether soul or body—but rather as continuity of consciousness:

“As far as this consciousness can be extended backwards to any past action or thought, so far reaches the identity of that person.”

This perspective treats identity as based on memory and self-awareness, influencing modern philosophy of personal identity, ethics, and law.

5. Political Philosophy: Life, Liberty, and Property

Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1689) is a foundational political text advocating natural rights and government by consent. It includes:

- First Treatise: A rigorous refutation of hierarchical authority based on patriarchal biblical models.

- Second Treatise: Outlines a theory of government grounded in natural law, property, social contract, and limited government.

Locke asserted that in the state of nature, all are free and equal, governed by natural law that prohibits harming others’ life, liberty, or property. Property rights arise when individuals mix their labor with resources (e.g., by farming empty land), transforming it through effort.

The social contract forms government: individuals consent to a community with powers of legislation and execution. If rulers violate natural rights or betray public trust, citizens retain the right to revolt.

Locke’s ideas on majority rule, limited government, and right of resistance underpin modern constitutional democracy and civil rights.

6. Religious Toleration

In A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), Locke argued for civil toleration of differing religious beliefs (excluding atheism and, initially, Catholicism). He maintained that the state can only enforce matters of public conduct, not private belief. Harmony is best achieved by religious freedom, not coercion.

Locke’s arguments contributed significantly to later Enlightenment thought about pluralism and the separation of church and state.

7. Education and Letters on Toleration

Locke also wrote Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693), advocating for balanced, gradual education. He emphasized:

- Physical care and healthy habits.

- Teaching by engaging the child directly with reality rather than lectures.

- Moral training through example, not punishment.

He argued that nurture shapes character and intellect, reconciling discipline with freedom and reason.

8. Influence and Legacy

Locke’s influence remains profound:

- Political Theory: He shaped Enlightenment liberalism, inspiring American Founders (e.g., Jefferson, Madison) and European constitutionalism.

- Philosophy of Mind: His ideas about empiricism, memory, and identity contributed to Hume, Reid, Butler, and contemporary debates in personal identity and cognitive science.

- Education: His humanistic, child-centered approach was influential on later educational theorists like Rousseau, Pestalozzi, and Dewey.

- Religious Freedom: Locke’s toleration principles remain central to modern secular-liberal democracies.

9. Criticisms and Debates

Locke has been criticized on several fronts:

- His labor theory of property struggles to account for issues of land appropriation and inequality.

- Some argue his blank-slate model underestimates innate cognitive structures—a critique echoed by modern cognitive science and Chomsky’s views on universal grammar.

- Critics of the social contract theory question whether genuine consent is required or possible in real societies.

- His exclusion of atheists and Catholics from full toleration has been seen as inconsistent.

Nonetheless, Locke’s writings continue to be central in political philosophy, epistemology, and liberal theory.

10. Summary and Conclusion

John Locke’s philosophy continues to shape modern thought in essential ways:

- Empiricism undergirds science and democracy.

- Political liberalism affirms life, liberty, property, and government by consent.

- Human equality and toleration sustain plural societies.

- Education built on individual centeredness cultivates responsible, rational citizens.

His legacy reminds us that knowledge is crafted through experience, human rights are grounded in natural law, and society flourishes under freedom constrained by reason. Even centuries later, Locke remains a guiding figure in democratic ideals and rational pluralism.