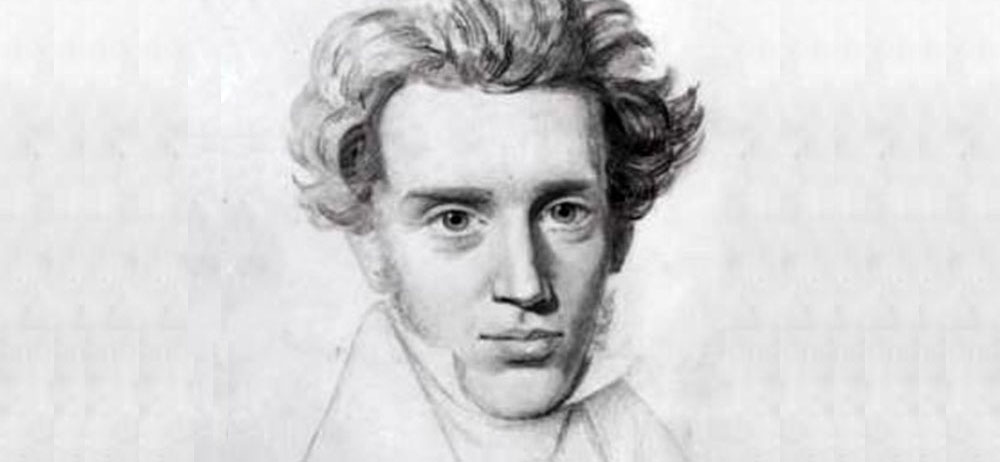

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (1813–1855) was a Danish philosopher, theologian, poet, and social critic, widely regarded as the father of existentialism. Although largely unrecognized in his own time, Kierkegaard’s writings addressed the most fundamental questions of human existence—faith, individuality, anxiety, despair, and freedom—in a way that would profoundly influence later existentialist thinkers such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Martin Heidegger, Simone de Beauvoir, and Karl Jaspers.

Kierkegaard’s thought is distinctive for its deeply personal, often ironic and poetic style. Rather than systematizing knowledge as his contemporary Hegel attempted, Kierkegaard focused on the lived experience of the individual, especially in relation to God. For him, philosophy was not about abstract theorizing but about passionately confronting one’s own existence.

Life and Context

Søren Kierkegaard was born on May 5, 1813, in Copenhagen, Denmark, into a wealthy but melancholic family. His father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, was a stern and deeply religious man who had a strong influence on Søren’s character and worldview. The elder Kierkegaard instilled in his son a profound sense of guilt, sin, and religiosity—elements that permeate Søren’s later writings.

Kierkegaard studied theology and philosophy at the University of Copenhagen. Although he trained to become a pastor, he never entered the clergy. Instead, he pursued a life of writing, reflection, and seclusion. A pivotal moment in his life was the broken engagement to Regine Olsen, a woman he loved deeply but left—ostensibly for religious and philosophical reasons. This decision haunted him for the rest of his life and became a symbol of the existential conflict between love, duty, and divine calling.

Kierkegaard lived a relatively short and solitary life, dying in 1855 at the age of 42. His later years were marked by increasingly sharp critiques of the Danish Church, which he believed had become complacent and worldly. Though largely ignored by his contemporaries, his posthumous influence has been immense.

Philosophy of the Individual

At the heart of Kierkegaard’s thought is the individual—not as a logical abstraction, but as a living, breathing person with choices, doubts, and passions. In contrast to the Hegelian system, which saw individuals as mere moments in the dialectical unfolding of Absolute Spirit, Kierkegaard insisted that each human being faces their own unique journey through life.

He believed that truth is subjective in the most important sense. While scientific or logical truths may be objective, existential truths—such as the meaning of one’s life or relationship with God—must be lived and internalized. As he famously wrote:

“Subjectivity is truth. Subjectivity is reality.”

This doesn’t mean that truth is relative or arbitrary, but that existential truth is something one must choose and commit to, often in the face of uncertainty and risk.

Stages on Life’s Way

In one of his most well-known frameworks, Kierkegaard outlines three stages or spheres of existence:

- The Aesthetic Stage – The life of pleasure, beauty, and immediate gratification. This stage is characterized by irony, detachment, and a fear of commitment. Ultimately, it leads to boredom and despair, as the individual realizes that no amount of aesthetic enjoyment can provide lasting meaning.

- The Ethical Stage – Here, the individual takes responsibility for their life, embracing duty, morality, and social commitments. It is a more mature form of existence, but still inadequate if lived apart from divine relationship. The ethical life recognizes the seriousness of choice and responsibility.

- The Religious Stage – The highest stage, where the individual makes a leap of faith into a personal relationship with God. This stage involves the absurd, paradox, and deep inwardness. It is not reached by reason alone, but by surrender and passionate commitment.

These stages are not rigid or necessarily sequential; rather, they represent different modes of living that one may adopt or oscillate between. The movement from aesthetic to religious life requires profound inner transformation.

Faith and the Leap

Kierkegaard’s understanding of faith is central to his thought and deeply radical. He viewed faith not as intellectual assent to doctrines but as a passionate, subjective commitment to the absurd. This is most famously explored in his book Fear and Trembling (1843), where he examines the biblical story of Abraham and Isaac.

In that narrative, Abraham is commanded by God to sacrifice his son Isaac. For Kierkegaard, Abraham becomes the “knight of faith” because he trusts in God beyond all reason—even when reason demands horror or rejection. This paradox, where one suspends the ethical for the sake of the divine, is the defining characteristic of true faith.

This leads to the notion of the “leap of faith”—a jump into the unknown, unprovable realm of belief and commitment. Kierkegaard saw this as both terrifying and necessary, for without such a leap, one remains trapped in despair or mere ethical formality.

Anxiety and Despair

Another key aspect of Kierkegaard’s existential psychology involves the concepts of anxiety (angst) and despair.

In The Concept of Anxiety (1844), Kierkegaard describes anxiety as the dizziness of freedom—a kind of existential vertigo that arises when one realizes the infinite possibilities of choice. It is not fear of something specific, but a deeper apprehension of the unknown and of one’s own freedom.

Despair, on the other hand, is the condition of not being one’s true self. In The Sickness Unto Death (1849), he defines despair as the misrelation of the self to itself. One may despair by refusing to be oneself (trying to escape one’s individuality), or by trying to construct a self without God. The only cure for despair is faith—to accept oneself as a creature in relation to the divine.

Critique of Christendom

Later in life, Kierkegaard became an increasingly sharp critic of the Danish Lutheran Church, which he believed had domesticated Christianity and turned it into a comfortable social institution. In his Attack upon Christendom, he lambasted the clergy for offering easy answers and cheap grace, rather than calling people to genuine discipleship and inward transformation.

For Kierkegaard, true Christianity was not a set of doctrines or rituals but a radical demand: to follow Christ in suffering, obedience, and inward faith. He believed that authentic Christianity was always at odds with worldly comfort and complacency.

Legacy and Influence

Although Kierkegaard was largely ignored during his lifetime and considered eccentric by many, his influence in the 20th century has been enormous:

- Existentialism: Kierkegaard is widely credited as the progenitor of existentialism, influencing Sartre, Camus, and Heidegger, though many of these thinkers rejected his religious conclusions.

- Theology: He deeply influenced Karl Barth, Paul Tillich, and Rudolf Bultmann, helping to shape neo-orthodox theology and Christian existentialism.

- Literature and Psychology: Writers like Franz Kafka, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Flannery O’Connor drew on Kierkegaardian themes. His work also anticipated aspects of depth psychology, especially the inner conflict and selfhood explored by Freud and Jung.

- Philosophy of Religion: His work remains central in discussions of faith, subjectivity, paradox, and the nature of religious belief.

Conclusion

Søren Kierkegaard stands as a singular voice in the history of philosophy—a thinker who rejected the cold abstractions of systematizers like Hegel in favor of a philosophy grounded in personal existence, authentic faith, and individual struggle. His legacy continues to resonate because he dared to ask the hardest questions: What does it mean to be a self? What does it mean to believe in God? What does it mean to live authentically?

Rather than offering easy answers, Kierkegaard challenged readers to confront their own inwardness, to embrace the freedom and responsibility of existence, and to risk the leap of faith. For him, the ultimate philosophical task was not to know but to be.

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

— Søren Kierkegaard