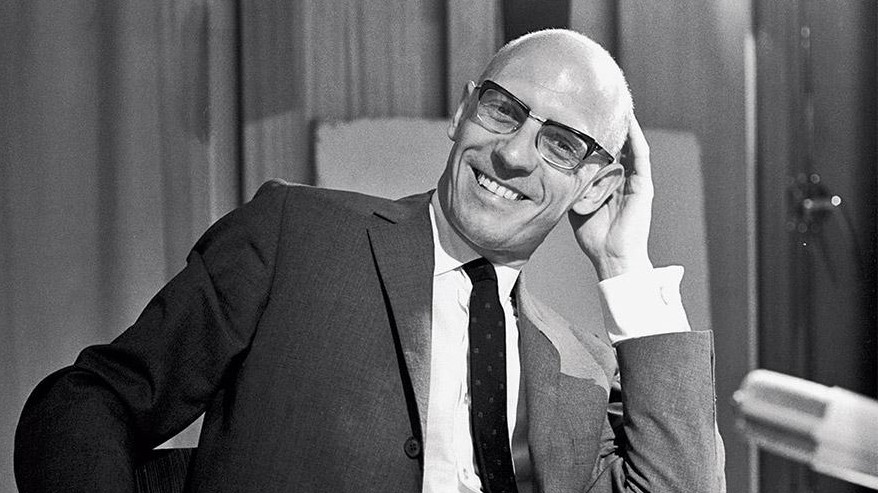

Michel Foucault (1926–1984) stands as one of the most influential and challenging philosophers of the 20th century. His work spans philosophy, history, sociology, political theory, and cultural studies, and it has profoundly shaped contemporary understandings of power, knowledge, and social institutions. Rather than developing a single, unified system, Foucault’s writings critically investigate the ways in which discourses and practices shape human experience, identity, and social order.

Early Life and Intellectual Context

Born in Poitiers, France, in 1926, Michel Foucault grew up in an intellectual milieu, eventually studying philosophy and psychology at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in Paris. His early career was influenced by existentialism, phenomenology, and structuralism, though he would later move beyond these frameworks.

His intellectual development took place in the aftermath of World War II and amid rapid social and political upheavals. This context shaped his interest in power relations, the construction of knowledge, and the way societies regulate and discipline individuals.

Archaeology of Knowledge and Discursive Formations

One of Foucault’s early methodological innovations is his concept of archaeology—a way of studying history not by focusing on events or ideas as isolated entities but by analyzing the underlying systems of thought or discourses that define what can be said, thought, and done in particular periods.

His 1966 work, The Archaeology of Knowledge, elaborates this approach. Foucault argues that knowledge is not a simple accumulation of facts but is deeply structured by rules governing discourses that produce meaning and truth. These rules determine what subjects and objects can be discussed, who can speak, and what is considered valid knowledge.

By studying the “archive” of discourses, Foucault uncovers how different epochs impose different regimes of truth. For example, medical knowledge in the 18th century operated under very different rules than in the modern era, shaping how health and illness were understood.

Power/Knowledge and the Rejection of Traditional Power Models

A cornerstone of Foucault’s thought is his concept of power/knowledge—the idea that power and knowledge are not separate but mutually reinforcing. Traditional political philosophy often treated power as something possessed by rulers or institutions and knowledge as neutral or objective. Foucault disrupts this dichotomy, showing how knowledge production is always an exercise of power.

In works like Discipline and Punish (1975), he examines how modern societies organize control and surveillance, shifting from overt physical punishment to more subtle, pervasive forms of discipline. Institutions such as prisons, schools, hospitals, and military barracks function to normalize behavior and produce “docile bodies” that conform to societal norms.

Power, for Foucault, is diffuse and capillary—it operates through networks and practices rather than simply through laws or decrees. This view challenges both Marxist and liberal notions of power as something possessed or wielded only by elites.

Discipline and Surveillance

Discipline and Punish is one of Foucault’s most famous works, where he traces the historical transformation of punishment—from public, violent spectacles to the modern prison system and disciplinary societies.

He introduces the metaphor of the Panopticon, a prison design proposed by Jeremy Bentham where a single guard can observe all inmates without them knowing whether they are being watched. This creates self-discipline because prisoners internalize the surveillance.

Foucault argues that modern society functions similarly: surveillance is embedded in everyday institutions, encouraging individuals to monitor themselves according to social norms. This pervasive discipline produces conformity and regulates behavior in a subtle but effective way.

The History of Sexuality and Biopower

In his multi-volume The History of Sexuality (begun in 1976), Foucault explores how sexuality is not simply repressed by society (as conventional wisdom might hold) but is actively constructed through discourse, regulation, and power.

He introduces the concept of biopower—the regulation of populations through techniques that manage life, health, reproduction, and mortality. Unlike traditional sovereign power that rules by the right to kill or punish, biopower governs through managing life processes and bodies, focusing on populations as subjects to be regulated.

This form of power is exercised in medicine, public health, education, and demography, shaping modern governance and individual identities.

Madness and Reason: The Birth of the Asylum

Foucault’s early book, Madness and Civilization (1961), examines how Western societies have historically defined and treated madness. He traces the shift from the Renaissance, where madness was sometimes linked to a form of divine insight or poetic inspiration, to the Enlightenment, when madness became something to be isolated, controlled, and treated in asylums.

Rather than accepting psychiatry’s claims at face value, Foucault critiques how the “mad” were excluded and marginalized as part of the broader processes of social control. His analysis reveals how the categories of “sanity” and “insanity” are socially constructed, tied to power relations rather than objective truths.

Subjectivity and Technologies of the Self

In his later work, Foucault turned to the question of subjectivity—how individuals constitute themselves as subjects within power relations. He studied “technologies of the self”: the practices, rituals, and ethical frameworks through which people shape their identities.

Drawing on ancient Greek and Roman practices of self-care and ethics, Foucault explored how individuals can resist and transform dominant power structures by creating alternative forms of subjectivity. This work influenced later fields such as queer theory, feminist theory, and postcolonial studies.

Influence and Legacy

Michel Foucault’s work has had a vast and lasting influence:

- Philosophy: He challenged and expanded philosophical understandings of power, knowledge, and subjectivity.

- Social Sciences: His methods inspired critical studies in sociology, anthropology, political science, and cultural studies.

- Humanities: Disciplines such as literary theory and history have been shaped by his approach to discourse and power.

- Political Theory: His conceptions of power challenge traditional political models, influencing post-structuralism, postmodernism, and critical theory.

- Activism and Critique: Foucault’s analyses of institutions continue to inform critiques of prisons, mental health systems, sexuality, and government surveillance.

Criticisms

Foucault’s work is not without controversy and critique:

- Some accuse his theory of power of being overly pessimistic or relativistic, suggesting it leaves little room for genuine resistance.

- Others find his dense writing style and sometimes elusive arguments difficult to engage with.

- Critics in philosophy and history have debated his selective use of historical evidence and skepticism about objective truth.

Nonetheless, his work remains foundational and provocative.

Conclusion

Michel Foucault’s intellectual legacy is profound and multifaceted. By interrogating the relationship between power, knowledge, and subjectivity, he unveiled the often-hidden mechanisms by which societies regulate and control individuals. His innovative methods and daring critiques opened new pathways in philosophy and the social sciences, forever changing how we think about truth, identity, and social order.

Foucault’s thought invites continual reflection and debate, challenging us to reconsider how we live within—and potentially resist—the complex webs of power that shape our world.