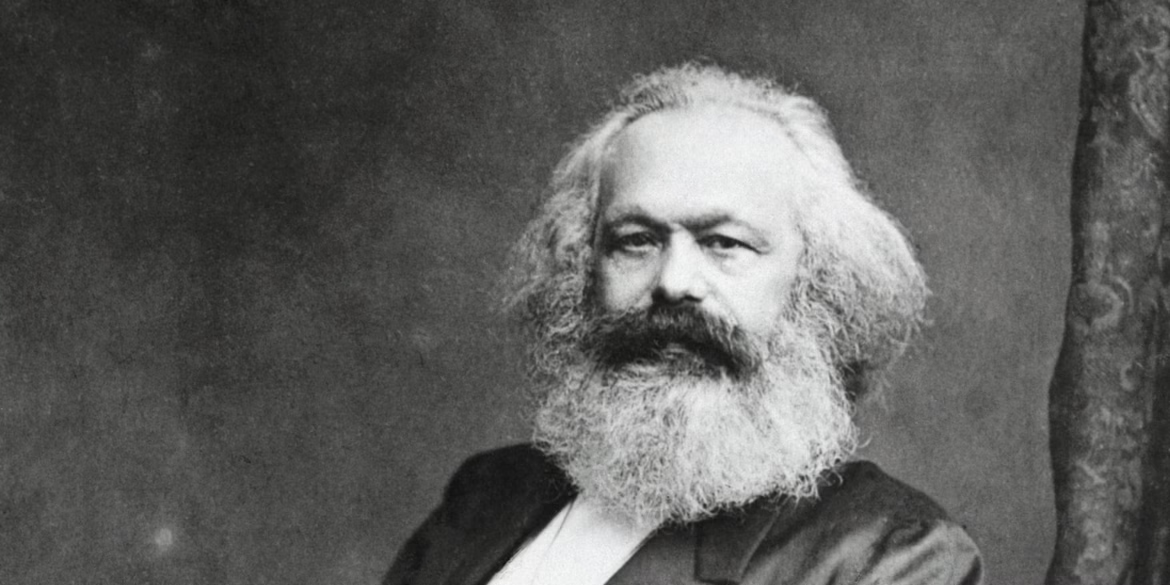

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, and revolutionary whose ideas fundamentally reshaped political theory and practice in the modern world. Often considered the father of communism, Marx is best known for his critique of capitalism and his theory of historical materialism. His work, especially The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Capital (Das Kapital, 1867), provided a radical framework for understanding history, class conflict, and social change.

While often polarizing, Marx’s thought has had a profound and lasting impact on philosophy, political science, economics, and social theory. To this day, debates around capitalism, inequality, labor, ideology, and revolution continue to be shaped by his ideas.

Early Life and Education

Karl Marx was born on May 5, 1818, in Trier, in the Rhineland region of Prussia (now Germany). His father was a lawyer and a liberal thinker who converted from Judaism to Lutheranism. Marx studied law, history, and philosophy at the universities of Bonn and Berlin. In Berlin, he was influenced by the Young Hegelians, a group of radical thinkers who used G. W. F. Hegel’s dialectical method to critique religion and politics.

Initially interested in academic philosophy, Marx wrote a doctoral thesis on ancient Greek materialists such as Democritus and Epicurus. However, political repression in Prussia and Marx’s increasingly radical views soon ended any hopes for an academic career. He turned to journalism and revolutionary theory, eventually being forced into exile for much of his life.

Historical Materialism and Dialectics

One of Marx’s most important contributions to philosophy and social theory is his concept of historical materialism. This is the idea that material conditions—especially the mode of production and economic structures—shape social, political, and intellectual life.

Unlike idealist philosophers who emphasized the power of ideas, Marx argued:

“It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.”

This means that the way people produce and exchange goods—whether through slavery, feudalism, or capitalism—determines the class structure, institutions, laws, morality, and culture of a society.

Marx built upon Hegel’s dialectical method, which sees history as unfolding through contradictions and their resolution. But while Hegel’s dialectic was idealist (focused on the development of Spirit or Mind), Marx “turned Hegel on his head” by making the dialectic materialist. For Marx, history is a struggle between opposing social classes—the motor of historical change.

Alienation and Labor

A key aspect of Marx’s critique of capitalism is the idea of alienation. In his early writings, especially the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Marx describes how under capitalist conditions, workers become estranged from:

- The product of their labor – since it is owned and sold by others.

- The labor process itself – which is repetitive, exhausting, and controlled by others.

- Other workers – due to competition and lack of collective solidarity.

- Their own human nature – because creativity and self-expression are stifled.

Marx believed that labor should be a fulfilling expression of human potential, but under capitalism it becomes merely a means of survival. Workers are reduced to commodities—valued not as human beings, but for their productivity.

The Communist Manifesto and Class Struggle

In 1848, Marx and Friedrich Engels published The Communist Manifesto, one of the most famous political documents in history. Its stirring opening lines set the tone:

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

The Manifesto argues that all societies are divided into classes with conflicting interests. In modern industrial society, the primary antagonism is between the bourgeoisie (the capitalist class who own the means of production) and the proletariat (the working class who sell their labor).

Marx and Engels claim that capitalism, while historically progressive in overthrowing feudalism and revolutionizing production, is inherently unstable. It generates immense wealth, but concentrates it in the hands of a few, leaving the masses impoverished and exploited.

According to the Manifesto, capitalism sows the seeds of its own destruction by:

- Creating a large, increasingly impoverished working class.

- Centralizing economic power in fewer hands.

- Globalizing production and markets, thereby spreading the crisis.

The solution, they argue, is proletarian revolution: the working class must seize control of the means of production, abolish private property, and create a classless, stateless society—communism.

Das Kapital and the Critique of Political Economy

Marx’s magnum opus, Capital (Das Kapital), published in 1867, offers a detailed and systematic analysis of capitalism as an economic system. Its central concern is how value is created and appropriated in capitalist society.

Marx introduces the concept of surplus value, the source of capitalist profit. Workers are paid wages equivalent to the value of their labor power, but in the working day they produce more value than they receive in wages. This extra value—surplus value—is appropriated by the capitalist as profit.

This leads to the exploitation of labor, which is not merely a moral issue but an inherent feature of the capitalist mode of production.

Marx also analyzes:

- Commodification: everything, including human labor, becomes a commodity.

- Capital accumulation: the constant reinvestment of surplus value to expand capital.

- The falling rate of profit: over time, competition and mechanization reduce profitability.

- Economic crises: capitalism is prone to cycles of boom and bust, due to overproduction and underconsumption.

For Marx, these contradictions are not accidental but structural. They make capitalism historically transient—a stage in human development that will eventually be superseded by socialism and communism.

Revolution, State, and Ideology

Marx’s vision of revolution was not just a sudden insurrection but the culmination of deep economic and social contradictions. He believed that when the proletariat became conscious of their collective power and interests, they would rise up and transform society.

In this process, the state, which under capitalism serves the interests of the bourgeoisie, would eventually wither away after serving as a tool for working-class rule. Marx envisioned a future classless and stateless society, based on common ownership and democratic control of resources.

He also developed a theory of ideology, arguing that the dominant ideas in any society are those of the ruling class. Religion, law, philosophy, and culture often serve to justify and maintain existing power structures, masking exploitation and preventing revolutionary change.

Legacy and Influence

Karl Marx’s ideas have had an enormous impact on world history and intellectual thought:

- Political Movements: Marxism inspired revolutions and socialist movements around the world, most notably the Russian Revolution (1917) and the creation of the Soviet Union, as well as revolutionary movements in China, Cuba, Vietnam, and elsewhere.

- Philosophy and Social Theory: Marx influenced thinkers such as Antonio Gramsci, Georg Lukács, Louis Althusser, and the Frankfurt School. In the 20th century, Marxism intersected with existentialism, psychoanalysis, feminism, postcolonial theory, and critical theory.

- Economics and Sociology: Even non-Marxist economists and sociologists acknowledge Marx’s insights into class, labor, capital, and inequality.

- Contemporary Relevance: In an era of globalization, automation, income inequality, and labor precarity, Marx’s critique of capitalism has seen renewed interest among scholars and activists.

Conclusion

Karl Marx was a thinker of extraordinary depth and radical ambition. His intellectual legacy encompasses a profound critique of capitalism, a vision of human liberation, and a method for analyzing history and society.

While his predictions of inevitable revolution have not materialized as he envisioned—and the regimes claiming his name often betrayed his democratic ideals—Marx’s core insights into class struggle, exploitation, ideology, and economic power remain vital.

Whether one agrees with his prescriptions or not, understanding Karl Marx is essential for grappling with the structures and contradictions of modern society. He remains one of the most influential and controversial figures in the history of human thought—a philosopher of change who sought not only to interpret the world, but to change it.

“Philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.”

— Karl Marx, Theses on Feuerbach (1845)