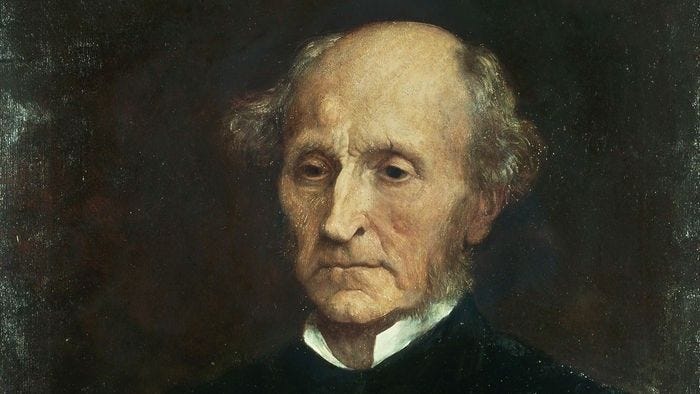

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) was one of the most important British philosophers and political thinkers of the 19th century. He is widely regarded as a towering figure in the development of liberalism, utilitarianism, political economy, and social reform. Through works such as On Liberty, Utilitarianism, The Subjection of Women, and Principles of Political Economy, Mill helped shape modern debates on freedom, justice, equality, democracy, and the limits of authority.

Mill’s thought combined the rationalist heritage of the Enlightenment with a deep concern for individual development and moral progress. Though committed to empiricism and logic, he also emphasized human emotions, character, and social wellbeing—making his philosophy a bridge between classical and modern liberalism.

Early Life and Education

John Stuart Mill was born in London in 1806 into a family committed to radical reform. His father, James Mill, was a historian, economist, and a close associate of Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism. Determined to make John a great reformer, James imposed a rigorous and highly unusual education upon his son.

Mill learned Greek at the age of three, Latin by eight, and was reading the works of Plato, Aristotle, and Euclid while most children were learning their times tables. He was immersed in philosophy, history, political economy, and logic from an early age and had little time for typical childhood pleasures.

Though brilliant, this intense upbringing came at a cost. At age twenty, Mill suffered a mental breakdown, precipitated by the realization that intellectual achievement alone could not fulfill his emotional or spiritual needs. It was through poetry (especially Wordsworth), literature, and the emotional life that he began to recover, gradually embracing a more humane and balanced outlook. This experience profoundly influenced his later views on individuality, happiness, and personal development.

Utilitarianism: The Ethics of Happiness

Mill is perhaps best known as the most influential proponent of utilitarianism, a moral theory originally developed by Jeremy Bentham, which holds that the right action is the one that maximizes overall happiness or utility.

In his book Utilitarianism (1861), Mill reformulated the doctrine to respond to critics who viewed it as overly hedonistic or simplistic. While Bentham had claimed that all pleasures are qualitatively equal and should be measured by intensity and duration, Mill introduced a qualitative distinction:

“It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.”

For Mill, higher pleasures—those of the intellect, imagination, and moral sentiment—are intrinsically more valuable than lower pleasures such as bodily sensations. This refinement gave utilitarianism a deeper moral dimension and made it more acceptable to educated audiences.

Moreover, Mill stressed that the utility principle must include the long-term good of humanity, not just immediate gratification. He argued that social institutions and moral education should cultivate a society in which people naturally care about others’ happiness, not just their own.

On Liberty: Individuality and the Limits of Authority

Mill’s On Liberty (1859) is one of the most influential works in the history of political thought and a foundational text for modern liberalism.

In it, Mill defends individual freedom against both state coercion and the “tyranny of the majority.” His central principle, often called the “harm principle,” is as follows:

“The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs or impede their efforts to attain it.”

According to Mill, individuals should be free to think, speak, and act as they please—provided their actions do not cause harm to others. This principle underlies modern views on freedom of speech, religious liberty, personal autonomy, and toleration.

What makes On Liberty so powerful is Mill’s emphasis on individuality as a vital element of wellbeing. Freedom is not just a political right—it is essential to self-development, creativity, and moral growth. In a conformist society where everyone is pressured to think and behave alike, human potential withers.

Mill’s warnings against social conformity, censorship, and paternalism remain highly relevant in modern debates over free expression, identity politics, and civil liberties.

The Subjection of Women: A Radical Feminist Text

Mill was also an early advocate for gender equality and women’s rights. His book The Subjection of Women (1869), co-written in spirit with his lifelong companion Harriet Taylor Mill, is a pioneering feminist text.

In it, Mill argues that the legal and social subordination of women is not only unjust but also harmful to the progress of society:

“The legal subordination of one sex to the other is wrong in itself, and now one of the chief hindrances to human improvement.”

He challenges the idea that gender roles are natural, claiming they are enforced through custom and coercion, not reason. He also asserts that society has lost immeasurable talent and innovation by excluding women from education, politics, and the professions.

Mill was one of the first Members of Parliament to advocate women’s suffrage, and he fought consistently for reforms in marriage law, property rights, and female education.

Political Economy and Social Reform

In Principles of Political Economy (1848), Mill attempted to reconcile economic liberalism with a concern for social justice. While accepting many of the insights of Adam Smith and David Ricardo, he argued that economic arrangements are not fixed by natural law—they can be changed to promote human flourishing.

Mill distinguished between the laws of production (which are determined by natural factors and efficiency) and the laws of distribution, which are shaped by social institutions and choices. This allowed him to support ideas like worker cooperatives, progressive taxation, and universal education—all radical at the time.

He envisioned a future society where people would work not just for profit, but for personal development and social good. He also endorsed environmental sustainability and warned against the “unbounded increase of wealth.”

Philosophy of Logic and Knowledge

Mill made substantial contributions to logic and the philosophy of science. His System of Logic (1843) argued that knowledge arises from empirical observation and inductive reasoning, in contrast to the purely deductive methods of earlier philosophers.

He believed in naturalism, the idea that human behavior and social institutions could be studied scientifically. Mill’s logic and methodology laid the groundwork for the social sciences, influencing figures like Auguste Comte and later positivists.

However, Mill also recognized the limits of empiricism. In his theory of liberty, ethics, and aesthetics, he acknowledged the role of intuition, imagination, and moral feeling, showing a flexibility often missing in strict empiricism.

Legacy and Influence

John Stuart Mill’s thought has had a lasting impact on a wide range of disciplines:

- In political theory, he helped define modern liberalism, defending civil liberties, individual rights, and democratic participation.

- In ethics, he developed a more humane and defensible form of utilitarianism, one that continues to influence moral philosophers and public policy.

- In economics, he laid the groundwork for a more socially conscious approach to capitalism.

- In feminism, he was a rare male voice in the 19th century calling for full legal and social equality for women.

- In education, he argued that true learning involves both critical thinking and emotional cultivation.

While Mill has been criticized for inconsistencies—such as the tension between utilitarianism and individual rights—his commitment to reason, liberty, progress, and human dignity remains inspirational.

Conclusion

John Stuart Mill was a philosopher of complexity and compassion. His works reflect a deep concern for the human condition—not only how people live, but how they ought to live. He believed that society should aim not merely at prosperity or order, but at fostering free, thoughtful, and morally responsible individuals.

His vision of liberty is not license, but the freedom to grow and contribute. His utilitarianism is not a cold calculus, but an ethic of care and empathy. And his politics are not simply institutional, but personal—grounded in respect for each individual’s unique worth.

In an age still wrestling with questions of freedom, equality, justice, and human development, Mill’s voice continues to resonate. His life and work stand as a testament to the enduring power of reasoned inquiry, moral clarity, and hopeful reform.