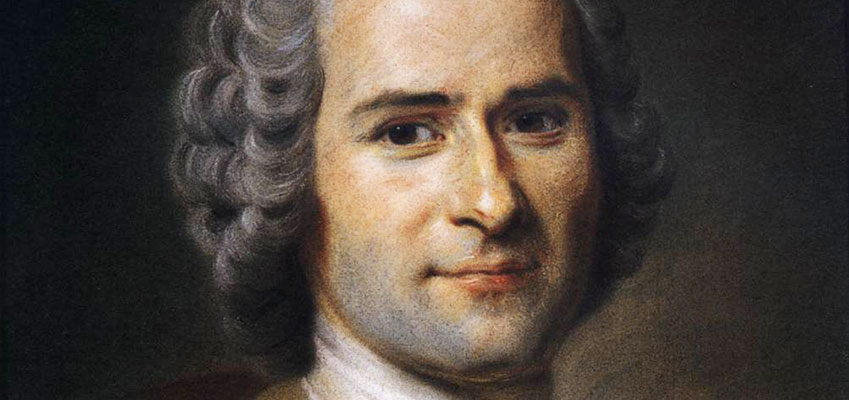

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) stands as one of the most profound and influential thinkers of the Enlightenment. His ideas about human nature, society, politics, education, and culture challenged the assumptions of his time and helped shape modern philosophy, political theory, and education. Rousseau’s work continues to resonate today, inspiring debates about freedom, democracy, inequality, and the relationship between individuals and society.

Early Life and Background

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1712. His early life was marked by hardship and instability. His mother died shortly after his birth, and his father abandoned the family when Rousseau was a child. Rousseau was largely self-educated, developing a deep love for reading and philosophy. His early exposure to the Calvinist environment of Geneva contrasted with his later cosmopolitan experiences in France and Italy, influencing his complex views on religion and society.

In his youth, Rousseau worked various jobs, including as a music tutor and secretary, before gaining recognition as a writer. His friendship with prominent Enlightenment figures, such as Denis Diderot and Voltaire, helped him gain entry into intellectual circles, but his independent thinking and radical ideas often set him apart.

Major Philosophical Themes

Rousseau’s thought spans many fields—political philosophy, education, literature, and moral theory—but some key themes recur throughout his work:

- The State of Nature and Human Nature

- The Social Contract and Political Legitimacy

- Education and the Development of the Individual

- The Critique of Civilization and Modernity

The State of Nature and Human Nature

One of Rousseau’s most famous contributions is his concept of the state of nature—a hypothetical, pre-social condition in which humans lived before the establishment of societies and governments. Unlike Hobbes, who viewed the state of nature as a violent “war of all against all,” Rousseau painted a more optimistic picture.

Rousseau argued that humans in the state of nature were essentially good, peaceful, and solitary creatures. They were driven by basic needs and guided by two key instincts: self-preservation and pity (compassion). According to Rousseau, humans’ natural freedom and equality were corrupted by the rise of society and private property.

His famous statement, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains,” reflects his view that the development of civilization and social institutions has led to inequality, dependence, and moral degradation. Rousseau saw the emergence of private property as the root cause of social conflict, inequality, and loss of freedom.

The Social Contract and Political Legitimacy

Rousseau’s political philosophy is best encapsulated in his masterpiece, The Social Contract (1762). Here he explores the conditions under which individuals might form a legitimate political community without sacrificing their freedom.

Rousseau argues that the legitimacy of political authority rests on the general will—the collective will of the people aimed at the common good. For Rousseau, true freedom is not simply doing whatever one wants but participating in the formulation of the laws that govern one’s life.

Key ideas from The Social Contract include:

- Popular Sovereignty: Sovereignty belongs to the people collectively. The people are the source of all legitimate political authority.

- General Will vs. Private Will: The general will aims at the common good, while private wills are self-interested. Citizens must sometimes subordinate their private interests to the general will to preserve freedom.

- Social Contract as a Mutual Agreement: Individuals agree to form a political community and abide by its laws in exchange for protection and the benefits of civil society.

- Freedom Through Law: By obeying laws that one has a hand in making, one remains free. This is contrasted with being subject to arbitrary power.

Rousseau’s concept of the general will has been both celebrated and criticized. It inspired revolutionary ideals of democracy and equality but was also interpreted (sometimes problematically) as a justification for authoritarianism when leaders claimed to represent the “general will.”

Education and the Development of the Individual

Rousseau’s educational philosophy, laid out in his novel Émile, or On Education (1762), is one of his most enduring contributions. Émile is a fictional account of the education of a boy named Émile, and through it, Rousseau outlines his ideas about how individuals should be raised.

He rejects the traditional emphasis on rote learning and discipline and instead promotes an education that respects the child’s natural development and curiosity. Some key principles of Rousseau’s educational thought include:

- Natural Education: Education should align with the child’s natural interests and stages of development rather than imposing artificial constraints.

- Learning by Experience: Children learn best through direct experience and interaction with the environment rather than passive reception of knowledge.

- Moral and Emotional Development: Education should nurture not only intellectual faculties but also the emotions and moral sense.

- Freedom and Autonomy: The goal of education is to cultivate autonomous individuals capable of reasoned judgment and moral responsibility.

Rousseau’s ideas about education influenced later educational reformers such as Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and Maria Montessori and remain relevant in contemporary debates on child-centered education.

The Critique of Civilization and Modernity

Throughout his works, Rousseau expressed deep skepticism about the progress of civilization. He admired the simplicity and freedom of pre-social human life and lamented how society’s institutions—property, inequality, competition—had led to corruption and unhappiness.

In his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (1755), Rousseau distinguishes between natural inequality (differences in age, health, strength) and moral or political inequality (created by social conventions and institutions).

He argues that social inequality is not natural but a product of historical developments, especially the institution of private property. Rousseau’s critique of civilization was revolutionary because it challenged the optimistic Enlightenment faith in progress and reason, introducing a more complex and often melancholic reflection on modernity.

Literary and Personal Dimensions

Rousseau was also a gifted writer and autobiographer. His Confessions (published posthumously) is considered one of the first modern autobiographies and offers a candid and introspective look at his life, thoughts, and struggles.

His writing style was passionate and accessible, combining philosophical rigor with literary flair. He was a controversial figure in his time, often at odds with other Enlightenment thinkers, and he experienced exile and censorship because of his radical ideas.

Legacy and Influence

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s influence is vast and multifaceted:

- Political Philosophy: His ideas about popular sovereignty and the social contract helped inspire the French Revolution and modern democratic theory. Figures like Robespierre and later democratic theorists drew upon Rousseau’s writings.

- Education: Rousseau’s child-centered approach laid the groundwork for progressive education and modern pedagogical methods.

- Romanticism: Rousseau’s emphasis on emotion, nature, and individuality influenced the Romantic movement in literature and the arts.

- Critique of Modernity: His reflections on inequality and corruption continue to inform social and political critiques of capitalism and modern society.

- Philosophy of Freedom: Rousseau’s complex understanding of freedom as participation in collective self-rule remains a central topic in political theory.

Conclusion

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a visionary thinker who challenged the foundations of political authority, social organization, and education. His belief in the essential goodness of human nature, the corrupting influence of society, and the possibility of a social contract grounded in freedom and equality continues to inspire and provoke.

Rousseau’s life and works remain a testament to the enduring power of philosophy to question the status quo and imagine new ways of living together. His legacy invites us to reflect critically on the nature of freedom, the meaning of justice, and the possibility of a society that nurtures both individuality and the common good.