Introduction

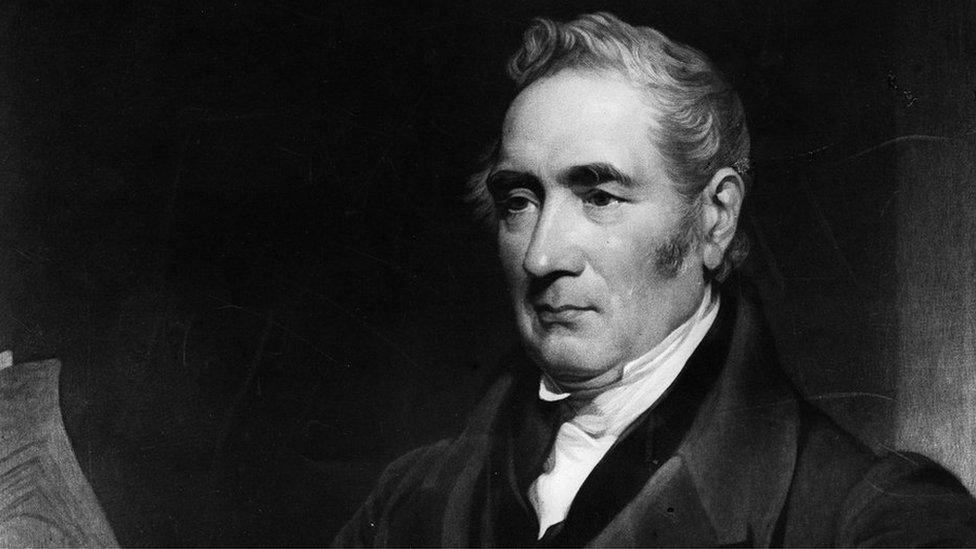

George Stephenson (1781–1848) stands as one of the great figures of the Industrial Revolution. Known as the “Father of Railways,” Stephenson was a self-taught mechanical and civil engineer whose work laid the foundation for modern railway transport. His most famous achievement was the development of the steam locomotive and the construction of the world’s first public railway line to use steam locomotives, the Stockton and Darlington Railway. He also designed the Rocket, a revolutionary steam engine that set the template for future locomotive design.

Stephenson’s story is also one of personal determination, rising from poverty and illiteracy to national fame and technological glory.

Early Life and Background

George Stephenson was born on June 9, 1781, in Wylam, a small village in Northumberland, England. His father, Robert Stephenson, worked as a fireman in a coal mine, tending the engines that pumped water from the mine shafts. The family lived in modest conditions, and George was one of six children.

Despite his mechanical aptitude, Stephenson did not attend school as a child due to his family’s poverty. From a young age, he worked as a cowherd and then followed his father into the collieries. He became a brakesman at Killingworth Colliery, responsible for controlling the winding gear that lifted coal and miners up and down the shafts.

Remarkably, Stephenson taught himself to read, write, and do arithmetic in his late teens, attending night school after work. This dedication to learning laid the groundwork for his future achievements in engineering.

Early Engineering Work

George Stephenson’s natural curiosity and mechanical ability became evident in his twenties. While working at Killingworth, he began repairing mine engines and eventually built a reputation for his ingenuity.

In 1814, Stephenson constructed his first locomotive, named Blücher, which was used to haul coal wagons on wooden rails at Killingworth. While similar in concept to other early locomotives (such as those by Richard Trevithick), Blücher was more reliable and efficient. It ran at about 4 mph and could pull 30 tons of coal.

The success of Blücher led to more commissions, and Stephenson began to think seriously about how steam locomotives could transform transportation beyond industrial sites.

The Stockton and Darlington Railway

By the 1820s, Britain’s growing industries needed better transportation networks. Roads were poor, and canals were slow and inflexible. Railways offered a promising alternative.

In 1821, George Stephenson was appointed chief engineer for the proposed Stockton and Darlington Railway, a 25-mile line intended to transport coal from mines near Shildon to the port at Stockton-on-Tees. He convinced the project’s backers to use steam locomotives instead of horses, a decision that would prove historic.

On September 27, 1825, the Stockton and Darlington Railway opened. Stephenson’s locomotive, named Locomotion No. 1, pulled a train carrying passengers and goods, making it the first public railway in the world to use steam traction. The event drew large crowds and was a stunning success. Though the train moved at just 15 mph, it was faster than anything previously available for land transport.

This railway marked the birth of modern rail travel and proved the viability of steam-powered locomotion on a public scale.

The Rocket and the Rainhill Trials

Building on the success of the Stockton and Darlington line, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was conceived in the late 1820s. It was to be a double-track railway connecting two major cities, which posed significant engineering challenges—bridging rivers, cutting through hills, and crossing unstable bogs like Chat Moss.

Stephenson was again appointed chief engineer. To determine the best locomotive for the line, the railway company held a competition in 1829 known as the Rainhill Trials.

Stephenson and his son Robert Stephenson designed a new locomotive, The Rocket, which featured several innovations:

- A multi-tube boiler for more efficient steam generation.

- A blast pipe that increased draft through the fire and improved fuel combustion.

- A cylinder configuration at an angle to drive the wheels more effectively.

The Rocket won the Rainhill Trials easily, achieving speeds of up to 30 mph and demonstrating reliability over long distances. Its success convinced railway companies across Britain and abroad to adopt steam locomotives as the standard.

Expansion of the Railways

Following the Rocket’s triumph, Stephenson was at the forefront of railway development across Britain. He was involved in building many important railway lines, including:

- Liverpool and Manchester Railway (opened 1830) – the world’s first fully operational passenger and freight railway using only steam power.

- Grand Junction Railway, London and Birmingham Railway, and North Midland Railway, all of which laid the foundation of Britain’s national railway network.

Stephenson insisted on a standard gauge of 4 feet 8½ inches, which is still used today as the standard rail gauge worldwide. This decision, based on earlier wagonway gauges, helped to standardise railway construction.

Stephenson’s Legacy

1. Technical Innovations

George Stephenson’s work was foundational in railway engineering:

- His locomotives were more practical, robust, and scalable than earlier designs.

- He standardised rail design and construction methods.

- He revolutionised transportation, turning railways from a novelty into the backbone of 19th-century commerce.

2. Impact on Society and Economy

Railways transformed society in countless ways:

- Faster transport of goods and people enabled national markets and urbanisation.

- New towns and industries emerged along railway lines.

- The railway system supported economic growth, job creation, and greater social mobility.

George Stephenson’s efforts directly contributed to the expansion of the Industrial Revolution, and by extension, to the modern world economy.

3. Recognition and Influence

Though born into poverty, Stephenson rose to become a national hero. He was admired for his practical genius, humility, and work ethic. In later life, he became a respected figure in engineering circles and a mentor to younger engineers.

His son, Robert Stephenson, became an equally famous railway engineer, continuing the family legacy and advancing rail transport throughout the world.

Personal Life and Death

George Stephenson was married twice and had two children, although only Robert survived to adulthood. After retiring from engineering, he moved to Tapton House near Chesterfield, Derbyshire, where he took an interest in farming and geology.

Stephenson died on August 12, 1848, at the age of 67. He was buried in Holy Trinity Church, Chesterfield.

Conclusion

George Stephenson’s journey from an illiterate miner’s son to the “Father of Railways” is an inspiring story of self-made success and innovation. His contributions to mechanical engineering, transportation, and industrial development altered the course of history.

Through his persistence, technical ingenuity, and vision, he helped shrink distances, accelerate commerce, and change how people lived and worked. Today, his legacy lives on every time a train runs on a track—a powerful testament to his life’s work.