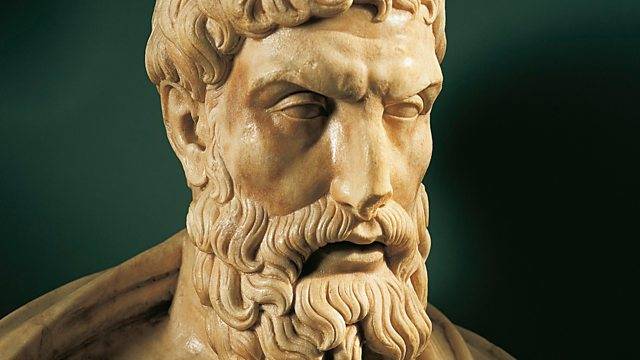

Epicurus (341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and the founder of Epicureanism, a philosophical system that emphasized the pursuit of happiness through rational living, friendship, and the elimination of unnecessary desires. Often misunderstood as a mere advocate of sensual indulgence, Epicurus in fact preached a lifestyle rooted in moderation, self-control, and intellectual clarity. His ultimate goal was not hedonism in the vulgar sense, but a life free from pain and mental disturbance—a state he called ataraxia, or tranquility.

Though many of his original writings have been lost, the essence of Epicurean philosophy survives through fragments, letters, and the poetic work De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things) by the Roman poet Lucretius. Epicurus’ teachings have had a lasting influence on both classical and modern thought, from ancient Rome to the Enlightenment and beyond.

Life and Historical Background

Epicurus was born on the island of Samos, a Greek colony, in 341 BC. His parents were Athenians, and he later moved to Athens, where he founded his own philosophical school known as “The Garden.” This school was unique in several ways: it accepted women and slaves, it emphasized communal living, and it promoted an egalitarian ethos.

Unlike the grand public lectures of Plato’s Academy or Aristotle’s Lyceum, Epicurus’ Garden was more intimate, focusing on friendship, discussion, and daily reflection. The Garden was not just a school of thought, but a way of life. Epicurus lived there with his students, embodying his teachings through example.

He wrote extensively—over 300 works, according to ancient sources—though only three of his letters and several key sayings have survived. His doctrines were summarized in the form of short principles or maxims, intended for memorization and practical use.

Philosophy of Pleasure and Ataraxia

Epicurus is most famous for his ethical theory based on pleasure (hedone). However, his conception of pleasure was far more refined and nuanced than critics often claim. For Epicurus, pleasure is the absence of pain in the body (aponia) and trouble in the soul (ataraxia). It is not the chase for luxury, indulgence, or excess, but the cultivation of a calm, simple, and thoughtful life.

“When we say that pleasure is the goal, we do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or those that lie in sensual enjoyment…but freedom from pain in the body and turmoil in the soul.”

— Letter to Menoeceus

Epicurus divided desires into three categories:

- Natural and necessary (e.g., food, shelter, friendship)

- Natural but unnecessary (e.g., luxury foods, fine clothing)

- Neither natural nor necessary (e.g., fame, power, wealth)

True happiness, he taught, comes from fulfilling only the first kind—those that are easy to satisfy and essential for life. The rest lead to anxiety, dependence, and frustration.

Thus, Epicurus advocated for moderation and self-sufficiency. The wise person does not seek more, but rather seeks to need less.

The Role of Philosophy

For Epicurus, philosophy was not a theoretical pursuit but a practical tool for living well. He believed that philosophy should heal the soul, much like medicine heals the body. In this sense, his teachings resemble those of the Stoics, though the two schools differed in many ways.

Philosophy, in the Epicurean sense, helps us analyze our desires, free ourselves from irrational fears, and find peace. It teaches us to seek the things that bring true pleasure—friendship, knowledge, and inner calm—while avoiding the sources of mental turmoil.

Epicurus insisted that philosophical inquiry should begin early and continue throughout life. “Let no one delay the study of philosophy while young,” he wrote, “nor weary of it when old.”

Atomism and Natural Science

Epicurus’ ethical teachings were underpinned by a materialist and naturalistic view of the universe. Influenced by Democritus, he believed that all things are composed of atoms—indivisible particles moving through the void. According to this view, the universe operates without the intervention of gods or supernatural forces.

This doctrine had several radical implications:

- The soul is material and mortal.

- The universe has no divine purpose or design.

- There is no afterlife—death is simply the end of consciousness.

“Death is nothing to us; for when we exist, death is not present, and when death is present, we no longer exist.”

— Letter to Menoeceus

By removing the fear of death and divine punishment, Epicurus sought to free people from superstition and anxiety. This naturalistic worldview was deeply controversial in the religious societies of antiquity, and many accused him of atheism—though he himself acknowledged the existence of gods, he believed they were indifferent to human affairs.

Friendship and the Good Life

Epicurus placed great emphasis on friendship as one of the chief sources of happiness. In contrast to the Stoics, who emphasized self-reliance, Epicurus saw deep emotional value in close personal relationships. He believed that friendship was not only a pleasure in itself but also a key to tranquility.

“Of all the things which wisdom provides to make us entirely happy, much the greatest is the possession of friendship.”

— Principal Doctrines, 27

In the Garden, Epicurus created a community where philosophical discussion and personal bonds could flourish. Friendship was seen not just as emotional support but as a rational and moral good, forming the foundation of a peaceful life.

Ethics of Simplicity

A defining feature of Epicurean ethics is its simplicity. The good life, for Epicurus, is neither grand nor heroic, but humble and easily attainable. He famously said, “If you wish to be rich, do not add to your money but subtract from your desires.”

The Epicurean sage is content with little, enjoys quiet reflection, and avoids the dangers of fame, politics, and public ambition. Such pursuits, Epicurus believed, entangle us in envy, fear, and endless striving.

This simplicity also extended to food, clothing, and other bodily pleasures. While Epicurus did not condemn enjoyment, he warned against becoming a slave to desire. The goal was not asceticism, but balance.

Misunderstanding Epicurus

Throughout history, Epicurus has often been misrepresented as a hedonist in the worst sense—someone who advocates for unchecked indulgence. This distortion began in antiquity, when rival philosophers (especially Stoics and Christians) painted Epicureanism as morally corrupt or godless.

However, Epicurus himself explicitly rejected luxury and excess. His life was austere, his diet frugal, and his philosophy deeply ethical. Modern readers, thanks in part to scholars and the rediscovery of On the Nature of Things, have reclaimed the true image of Epicureanism as a noble, humanistic philosophy.

Influence and Legacy

Epicurus’ influence has been far-reaching. In the Roman world, he was revered by thinkers like Lucretius, Horace, and even Cicero (though with criticism). Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura brought Epicurean ideas to life through vivid poetry and natural philosophy, preserving his views for future generations.

During the Renaissance and Enlightenment, Epicurean thought found new champions in Gassendi, Jefferson, Diderot, and others who admired his materialism and rationalism. Thomas Jefferson even declared himself an Epicurean, writing that “the doctrine of Epicurus…is calculated to give the greatest amount of happiness that can be enjoyed in this life.”

In modern times, Epicurus is often regarded as a precursor to secular humanism, natural science, and even aspects of modern psychology. His focus on well-being, freedom from anxiety, and rational pleasure resonates in contemporary discussions about happiness and ethics.

Conclusion

Epicurus stands out among ancient philosophers for his radically human-centered ethics, his commitment to peace of mind, and his naturalistic understanding of the world. Far from promoting indulgence, he advocated a life of reason, friendship, moderation, and simplicity.

His teachings encourage us to let go of irrational fears, embrace the pleasures that are natural and easy to attain, and cultivate meaningful relationships. In a world still plagued by anxiety, materialism, and the fear of death, Epicurus’ philosophy offers a gentle yet powerful remedy—a guide to living well with less.

As Epicurus himself wrote, “He who understands the limits of life knows that that which removes pain, and makes life most pleasant, is easy to attain.”