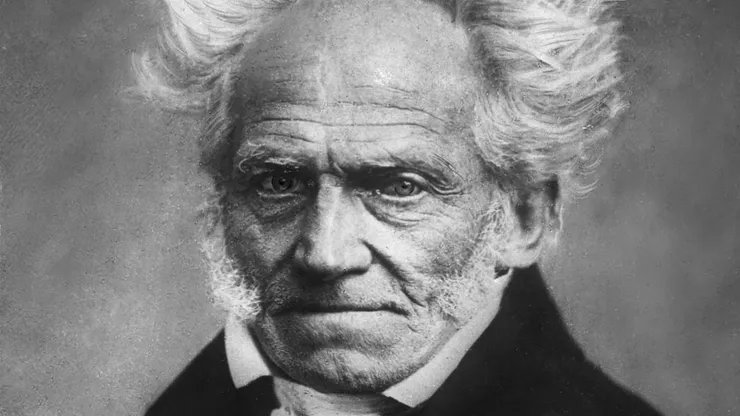

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) stands out in the history of philosophy for his deeply original, often bleak, yet powerfully insightful system of thought. Often labeled the “philosopher of pessimism,” Schopenhauer constructed a worldview that placed human suffering at the center of existence and introduced the concept of the Will as the ultimate reality underlying all phenomena. Though neglected during much of his life, his influence became immense in later decades, shaping thinkers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Richard Wagner, Thomas Mann, and Albert Einstein.

Early Life and Influences

Schopenhauer was born in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) to a wealthy merchant family. His father, a cosmopolitan and worldly man, ensured that Arthur received a broad education, including travel throughout Europe. However, Arthur’s father died—possibly by suicide—when Schopenhauer was just a teenager, a traumatic event that may have contributed to the darker tone of his worldview.

Though initially directed toward a career in business, Schopenhauer turned to academia, studying at the University of Göttingen and then in Berlin. He was especially influenced by Immanuel Kant, whose Critique of Pure Reason he described as the most important book ever written. Yet Schopenhauer also diverged from Kant by proposing a metaphysical solution to the world Kant left unknowable: the thing-in-itself.

Another major influence on Schopenhauer was Indian philosophy, particularly the Upanishads and Buddhism, which he encountered through translations. These traditions resonated with his view of life as suffering and reinforced his ascetic tendencies.

The World as Will and Representation

Schopenhauer’s magnum opus, Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (The World as Will and Representation, first published in 1818 and revised in 1844), lays out his fundamental metaphysical and epistemological system.

He makes a fundamental distinction between two aspects of reality:

- The World as Representation (Vorstellung): This is the phenomenal world—the world we experience, which is mediated through our senses and cognitive faculties. Schopenhauer adopts and adapts Kant’s idealism, arguing that everything we perceive is filtered through our mental structures, particularly the forms of space, time, and causality.

- The World as Will (Wille): Behind this veil of appearances lies a deeper metaphysical reality: the Will. This Will is a blind, aimless, insatiable striving that underlies everything—from natural phenomena to human desire. It is irrational and without purpose, the true essence of all things.

In humans, this Will is most clearly observed in desire, striving, and instinct. We are not rational beings guided by logic but rather slaves to a restless, ceaseless energy that perpetuates suffering.

The Nature of Human Suffering

For Schopenhauer, life is fundamentally characterized by suffering. Why?

Because the Will is never satisfied. Once one desire is fulfilled, another arises. Happiness is merely the temporary cessation of a desire—not a positive state in itself. Thus, life oscillates between pain (the frustration of unfulfilled desire) and boredom (the emptiness that follows temporary satisfaction).

He wrote:

“All striving springs from want or deficiency, from dissatisfaction with one’s condition, and is therefore suffering so long as it is not satisfied. No satisfaction, however, is lasting; on the contrary, it is always merely the starting-point of fresh striving.”

This relentless nature of desire is not limited to humans. All beings strive—from animals to plants to inanimate nature—driven by the Will.

Art, Aesthetics, and the Escape from Will

Despite his pessimism, Schopenhauer does not advocate nihilism. He identifies art—particularly music—as one of the few ways we can temporarily escape the tyranny of the Will.

In aesthetic experience, especially when contemplating great works of art or nature, the individual can momentarily lose the sense of self and become a “pure will-less, painless, timeless subject of knowledge.” This detachment allows for a rare experience of peace and objectivity.

Music holds a special place in Schopenhauer’s philosophy. Unlike the other arts, which represent the world as appearance, music is the direct expression of the Will itself. This idea would greatly influence composers like Richard Wagner and thinkers such as Nietzsche.

Ethics and Compassion

Schopenhauer’s ethics derive from his metaphysical view. If the Will underlies all beings, then there is no true separation between individuals. He sees compassion as the highest moral value—when we act compassionately, we overcome the illusion of individuality and recognize the shared suffering of all life.

Unlike Kant, who emphasized duty and reason in ethics, Schopenhauer rooted morality in feeling, particularly empathy. Asceticism and self-denial, seen in saints or monks, represent the highest moral achievements, as such individuals renounce the Will and its demands altogether.

This ethical framework bears resemblance to Buddhist compassion and Christian mysticism, and it diverges sharply from Western rationalist moral theories.

Reception and Influence

During his lifetime, Schopenhauer was largely ignored, overshadowed by thinkers like Hegel, whom he despised and mocked. He once scheduled his lectures at the same time as Hegel’s at the University of Berlin, only to find himself speaking to an empty room.

However, in the latter half of the 19th century, Schopenhauer gained considerable recognition:

- Friedrich Nietzsche, at first a devoted disciple, later broke with Schopenhauer’s ascetic ethics but remained influenced by his psychology and aesthetics.

- Sigmund Freud acknowledged Schopenhauer as a precursor in understanding the unconscious and the irrational drives that govern human behavior.

- Richard Wagner, the composer, was inspired by Schopenhauer’s ideas on music and Will.

- Thomas Mann, Leo Tolstoy, and other writers were deeply influenced by Schopenhauer’s profound exploration of suffering and human nature.

In the 20th century, existentialist and psychoanalytic thinkers found in Schopenhauer a kindred spirit who anticipated many of their concerns.

Criticisms

Despite his brilliance, Schopenhauer’s philosophy has faced criticisms:

- His metaphysical concept of the Will is seen by some as overly speculative and not empirically grounded.

- His pessimism is considered by many to be exaggerated or one-sided, neglecting the richness and joy of human experience.

- His views on women, which he described in overtly misogynistic terms, have rightly drawn widespread condemnation.

- Some critics argue that he failed to engage seriously with social and political realities, focusing instead on individual suffering.

Nevertheless, even his critics acknowledge the literary beauty, psychological depth, and radical originality of his work.

Conclusion

Arthur Schopenhauer remains a unique figure in the philosophical tradition. His system, built upon the bleak recognition of suffering and the irrational nature of existence, offers a profound critique of optimistic Enlightenment thought and modern notions of progress. Yet his pessimism is not nihilistic: through art, compassion, and ascetic discipline, Schopenhauer points to ways in which we can confront and, to some extent, transcend the tragic condition of life.

He challenges readers to confront the darker aspects of the human condition without illusion, while still finding paths toward meaning, connection, and inner peace. For this reason, Schopenhauer continues to speak powerfully to those who seek truth not in comfort, but in depth.