Introduction

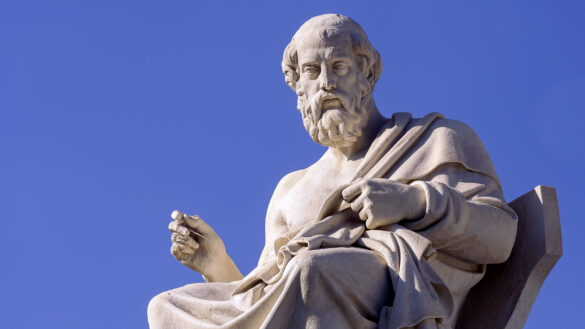

Plato (c. 427–347 BCE) was a Greek philosopher whose ideas have shaped the course of Western thought for over two millennia. A student of Socrates and the teacher of Aristotle, Plato stands at the heart of ancient philosophy, bridging the pre-Socratic world with a systematic and far-reaching body of work that continues to inspire philosophers, scientists, theologians, and political theorists.

Plato’s contributions range across metaphysics, ethics, epistemology, politics, education, and aesthetics. He founded the Academy in Athens, often regarded as the first university in the Western world. His dialogues, featuring Socratic questioning, remain foundational texts in philosophy, combining literary beauty with intellectual rigor. Through his concept of the Forms, his theory of the soul, and his vision of the ideal state, Plato laid the groundwork for countless philosophical debates that endure today.

Early Life and Background

Plato was born into an aristocratic family in Athens during a time of political turmoil. His birth name was Aristocles, but he became known as Plato, possibly a nickname derived from “platos,” the Greek word for broad, referring either to his physique or his wide-ranging intellect.

His early education included subjects typical for a young Athenian noble: gymnastics, poetry, music, and philosophy. In his twenties, Plato became a devoted student of Socrates, whose dialectical method of questioning and relentless pursuit of truth left a profound impact on him. The execution of Socrates in 399 BCE deeply influenced Plato, motivating him to explore the flaws in Athenian democracy and seek a more just and rational society.

The Dialogues and the Socratic Method

Plato wrote more than 30 philosophical dialogues, nearly all of which feature Socrates as the main character. These works serve as both philosophical treatises and dramatic conversations, blending literary art with philosophical inquiry.

The Socratic method, central to these dialogues, involves asking a series of probing questions to expose contradictions and clarify ideas. This method seeks not to impart facts but to stimulate critical thinking and self-examination. In early dialogues such as Euthyphro, Apology, and Crito, Plato captures the ethical concerns of Socrates, focusing on virtue, justice, and piety.

As Plato’s thought matured, his dialogues became more elaborate and speculative, culminating in works like The Republic, Phaedrus, Symposium, Timaeus, and Laws.

Theory of Forms

Perhaps Plato’s most enduring philosophical contribution is his Theory of Forms (or Ideas). According to this theory, the material world we perceive with our senses is only a shadow or imitation of a higher, unchanging reality.

For every object or concept in the physical world—such as beauty, justice, or a tree—there exists a corresponding Form that is perfect, eternal, and non-material. These Forms exist in a realm accessible not through the senses but through the intellect.

In The Republic, Plato famously illustrates this with the Allegory of the Cave. Prisoners in a cave see only shadows cast on a wall and believe them to be reality. One prisoner escapes, discovers the world outside, and sees the true sources of the shadows—the Forms. This allegory symbolizes the philosopher’s journey from ignorance to knowledge, from illusion to truth.

Epistemology and the Nature of Knowledge

Plato believed that true knowledge (episteme) is distinct from opinion (doxa). Since the sensory world is constantly changing, it can only give us unreliable information. Knowledge, by contrast, must be about what is eternal and unchanging—the Forms.

In dialogues such as Meno and Phaedo, Plato argues for the idea of anamnesis, or recollection. He suggests that the soul, having existed in the realm of Forms before birth, possesses innate knowledge that is “remembered” through philosophical inquiry.

This epistemological stance laid the foundation for rationalism, the belief that reason is the primary source of knowledge, as later developed by philosophers like Descartes and Kant.

The Tripartite Soul and Ethics

In The Republic, Plato outlines a vision of the soul consisting of three parts:

- Rational – seeks truth and wisdom.

- Spirited – seeks honor and is responsible for courage and indignation.

- Appetitive – seeks physical pleasures, desires, and material gain.

A just soul is one in which reason governs, assisted by spirit, with appetite kept in check. This internal harmony mirrors Plato’s vision of a just society.

Plato’s ethical philosophy centers on the idea that virtue is knowledge—that to know the good is to do the good. He believes that living a virtuous life, in accordance with reason and the Forms, leads to eudaimonia, or human flourishing.

Political Philosophy and the Ideal State

Plato’s political theory, most fully developed in The Republic, envisions an ideal society governed by philosopher-kings—individuals trained in philosophy and ruled by reason. He divides society into three classes that mirror the soul:

- Rulers (rational) – philosophers who seek truth and govern wisely.

- Guardians (spirited) – soldiers who defend the state.

- Producers (appetitive) – farmers, artisans, and merchants who provide for material needs.

Plato criticizes democracy as a flawed system that allows the ignorant masses to make decisions. He saw the trial and execution of Socrates as a failure of democratic Athens. Instead, he advocated for a meritocratic and hierarchical society where rulers are chosen based on wisdom and virtue.

Though criticized for its authoritarian elements, Plato’s political vision remains a cornerstone in political theory, prompting discussion on justice, governance, education, and the role of the state.

Plato’s Academy

Around 387 BCE, Plato founded the Academy in Athens, one of the first institutions of higher learning in the Western world. It attracted students from across the Greek world and flourished for centuries.

The Academy was a place not only for philosophical discussion but also for scientific and mathematical inquiry. Its most famous student was Aristotle, who would go on to develop his own philosophy in response to Plato’s teachings.

The Academy institutionalized the Socratic pursuit of wisdom, setting a precedent for universities and intellectual communities for generations to come.

Plato’s Legacy and Influence

Plato’s influence on Western thought is immense and enduring. His writings became central texts for Christian, Islamic, and Jewish philosophers in the medieval period. Thinkers like Augustine, Aquinas, Al-Farabi, and Maimonides engaged deeply with his ideas.

During the Renaissance, Plato’s emphasis on ideal forms, beauty, and the human soul inspired artists and humanists. In the modern era, his concepts influenced idealism, existentialism, and analytic philosophy.

His philosophical dialogues remain required reading in philosophy, literature, political theory, and ethics. Concepts such as Platonic love, Platonic ideals, and Platonism have entered everyday language.

Criticisms and Controversies

Plato’s philosophy is not without criticism. His Theory of Forms has been challenged for its abstractness and lack of empirical grounding. His political model in The Republic has been interpreted by some as totalitarian, subordinating individual freedom to the state.

Moreover, his dismissal of art as mere imitation in The Republic (calling it thrice removed from the truth) sparked debates in aesthetics. Aristotle would later reject much of Plato’s metaphysics, developing a more empirical and grounded approach to knowledge.

Despite these critiques, the depth, clarity, and systematic nature of Plato’s thought ensures his central place in the canon of philosophy.

Conclusion

Plato’s life and work represent a profound turning point in the intellectual history of humanity. He provided philosophy with a new language and structure, created a framework for understanding reality, and championed reason as the path to truth and justice.

His vision of a world of perfect Forms, his belief in the soul’s immortality, and his call for philosopher-rulers challenged people to rethink their assumptions about life, knowledge, and society. His Academy, dialogues, and philosophical legacy continue to inspire critical thinking and the pursuit of wisdom.

As long as questions about truth, justice, virtue, and the good life persist, Plato’s thought remains not only relevant but essential.