Introduction

Socrates (c. 470–399 BCE) is one of the most influential figures in Western philosophy. Though he left behind no written records himself, his legacy lives on through the works of his students, most notably Plato and Xenophon. He is often referred to as the “father of Western philosophy” because of his foundational role in the development of critical thinking, ethics, and epistemology.

Unlike the pre-Socratic thinkers who focused primarily on cosmology, metaphysics, and the nature of the physical world, Socrates turned philosophy toward human issues—such as virtue, justice, and knowledge. His unique method of dialectical questioning (now known as the Socratic Method) and his steadfast commitment to truth, even in the face of death, have made him an enduring symbol of philosophical inquiry and intellectual integrity.

Life and Background

Socrates was born in Athens, the cultural and intellectual center of ancient Greece, around 470 BCE. He was the son of a stonemason, Sophroniscus, and a midwife, Phaenarete. Little is known about his early life, though it is believed he received a standard Athenian education in poetry, music, and gymnastics, and later trained as a stonecutter like his father.

Socrates served as a hoplite (heavily armed infantryman) in the Athenian military during the Peloponnesian War and was noted for his courage and endurance. He married a woman named Xanthippe, with whom he had several children. Despite these personal details, most of what we know about Socrates comes from the writings of his students, especially Plato’s dialogues, which present him as the main character in philosophical debates.

The Socratic Method

One of Socrates’ most significant contributions to philosophy was his unique method of inquiry, known today as the Socratic Method. This approach involves asking a series of questions to help a person or group discover their beliefs and challenge their assumptions.

Rather than delivering lectures or claiming to know the truth, Socrates would engage others in dialogue, often pretending to be ignorant (a technique known as Socratic irony) in order to expose contradictions in their thinking. His goal was not to teach in the conventional sense, but to help others think more deeply and critically.

The Socratic Method is still used today in law schools, ethics discussions, and critical thinking exercises. It promotes a dialectical approach where ideas are refined through rigorous questioning rather than passive acceptance.

Philosophy and Key Ideas

Socrates focused on ethical questions and the pursuit of a virtuous life. He believed that knowledge and virtue were intimately connected—that to know the good was to do the good. In other words, wrongdoing was a result of ignorance rather than malice.

Among his key philosophical positions were:

1. “Know Thyself”

Socrates emphasized self-examination as the path to wisdom. He believed that an unexamined life is not worth living, a statement he famously made during his trial.

2. Virtue as Knowledge

For Socrates, all virtues (such as courage, justice, and piety) are forms of knowledge. If a person truly understands what is right, they will act accordingly. This was a revolutionary idea in a society where morality was often linked to tradition or divine decree.

3. The Pursuit of Truth

Socrates held that the truth should be pursued regardless of personal cost. He was critical of sophists—professional teachers who charged for their services and often used rhetorical skill to obscure truth rather than reveal it.

4. The Immortality of the Soul

Though Socrates did not develop a formal theory of the soul, he believed in its immortality and its capacity for reason. In Plato’s dialogue Phaedo, Socrates discusses the soul’s journey after death and expresses calm assurance in the face of his execution.

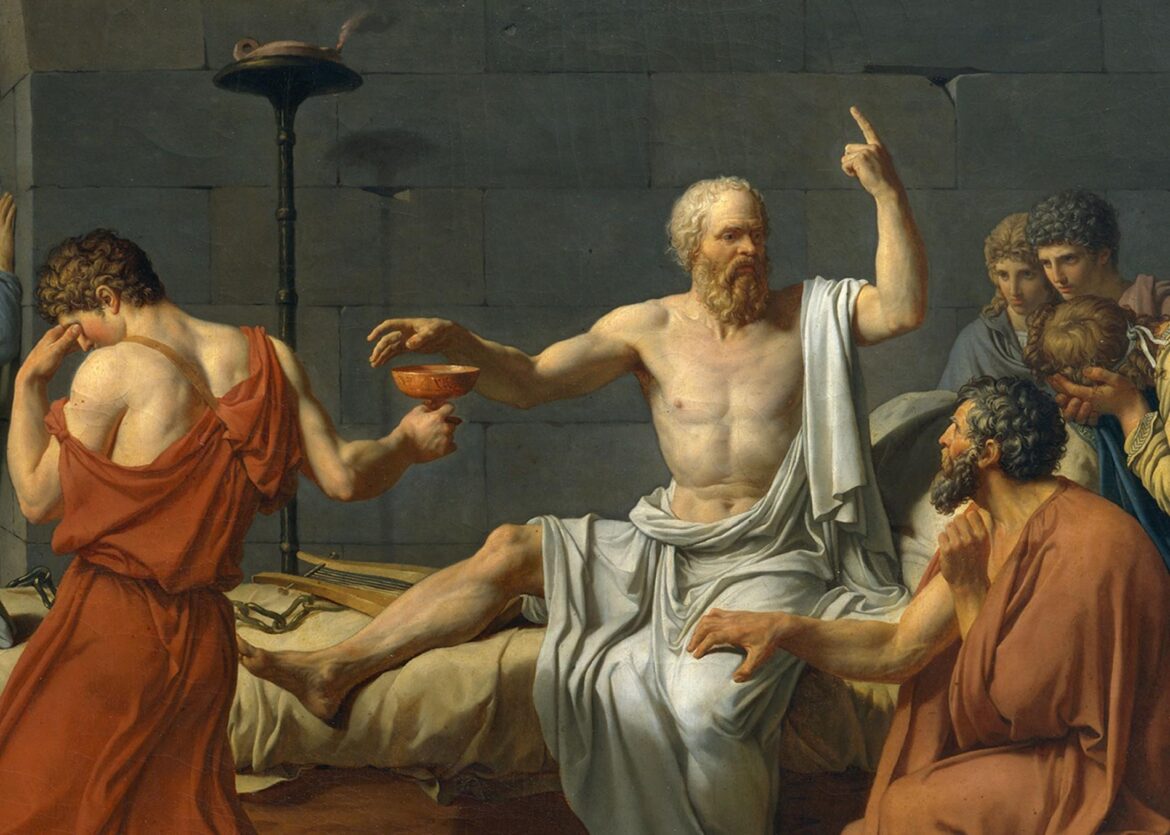

The Trial and Death of Socrates

In 399 BCE, Socrates was brought to trial on charges of impiety (not believing in the gods of the city) and corrupting the youth of Athens. The trial took place in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War, a period of social and political unrest in Athens. Many believed Socrates’ influence had contributed to the decline of Athenian democracy—particularly through his association with controversial figures like Alcibiades and Critias.

In his defense speech (Apology), as recorded by Plato, Socrates does not plead for mercy or attempt to sway the jury with emotion. Instead, he defends his role as a social and moral gadfly, claiming he was doing the city a service by encouraging critical thought and challenging complacency.

Despite his eloquence, Socrates was found guilty and sentenced to death. Given the opportunity to propose an alternative punishment, Socrates—characteristically ironic—suggested that he be rewarded with free meals for life. Eventually, he was ordered to drink a cup of hemlock, a poisonous plant. He did so calmly, discussing the nature of the soul with his friends until the end.

Legacy and Influence

Socrates’ death marked a turning point in Athenian thought and galvanized generations of philosophers. Though he wrote nothing, his ideas were preserved and expanded by his students, particularly Plato, who established the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world.

Plato’s dialogues—such as Apology, Crito, Euthyphro, and Phaedo—immortalize Socrates as a moral exemplar and intellectual hero. Through these works, Socrates became a symbol of intellectual integrity, critical thinking, and philosophical courage.

Socrates’ influence on Plato and, by extension, on Aristotle created a philosophical lineage that laid the foundations for Western rational thought. His method and ethical teachings influenced Stoicism, Christian theology, Islamic philosophy, and the Enlightenment thinkers like Descartes, Locke, and Kant.

Modern Relevance

The legacy of Socrates remains powerful in the modern world. His method of questioning and dialogue is central to:

- Education: Encouraging students to question assumptions, engage in dialogue, and think critically rather than memorize facts.

- Law: Legal training often employs the Socratic Method to challenge students to analyze and defend complex positions.

- Ethics: Socratic thought underpins modern debates about justice, morality, and personal responsibility.

- Democracy: Socrates’ life poses questions about the tension between free speech and social order—a topic that remains highly relevant.

Socrates reminds us that philosophy is not just an abstract discipline but a way of life—one that demands courage, humility, and relentless inquiry.

Conclusion

Socrates remains a towering figure in the history of philosophy not because he offered definitive answers, but because he changed the very way we ask questions. His insistence on reasoning, his commitment to truth, and his moral integrity make him not only a foundational thinker but also an enduring role model.

He taught that wisdom begins in recognizing our ignorance, that truth is best approached through dialogue, and that living a good life requires deep self-examination. In his life and death, Socrates exemplified the philosophical spirit: humble, courageous, and unshakably devoted to the pursuit of virtue and truth.

More than two thousand years later, his voice still echoes in classrooms, courtrooms, and coffeehouses—the eternal questioner, always asking: “What is the good life?”