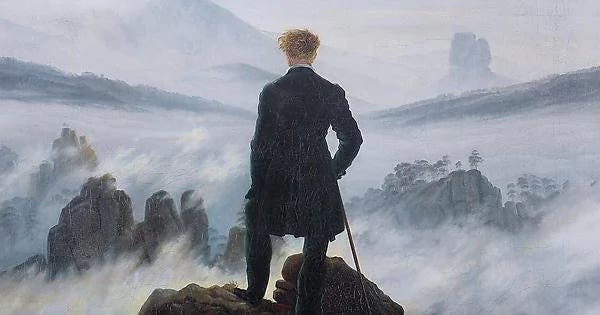

Thus Spoke Zarathustra (Also sprach Zarathustra), written by Friedrich Nietzsche between 1883 and 1885, stands as one of the most enigmatic and influential works of modern philosophy. A blend of philosophical treatise, poetic narrative, and religious parody, this work encapsulates Nietzsche’s most central ideas—Übermensch (Overman or Superman), eternal recurrence, the death of God, the will to power, and a new reevaluation of morality. Structured like a gospel or a prophetic sermon, the book is a fictional account of the prophet Zarathustra, who descends from his mountain solitude to share profound insights with humankind.

Unlike conventional philosophical texts, Thus Spoke Zarathustra is deeply allegorical and metaphorical. Its style is lyrical, at times cryptic, echoing the rhythm and authority of religious scripture, particularly the Bible. Nietzsche chose the figure of Zarathustra (the Persian prophet Zoroaster) not for historical reasons, but symbolically—Zarathustra was traditionally seen as the first moralist, the originator of a dualistic worldview of good versus evil. Nietzsche, seeking to overturn traditional morality, ironically chooses the same figure to herald a new philosophy that denies absolute dichotomies.

The Structure and Literary Form

The book is divided into four parts, each composed of various chapters containing Zarathustra’s teachings, encounters, parables, and visions. The episodic structure allows Nietzsche to explore a range of themes and ideas, from existential despair to spiritual rebirth.

Part One introduces Zarathustra’s return to humanity after ten years of solitude in the mountains. His first proclamation is that “God is dead,” a statement not meant to be taken literally, but as a metaphor for the decline of traditional Christian values in the modern age. With the death of God comes the collapse of objective morality, metaphysical certainty, and meaning as dictated by religion. Nietzsche does not view this as a catastrophe but as a liberation—a call for the creation of new values.

In response to the vacuum left by the death of God, Zarathustra introduces the idea of the Übermensch—a higher type of human being who creates his own values and lives with affirmation rather than resentment. “Man is something that shall be overcome,” says Zarathustra. The Übermensch is not merely a superior individual but a symbol of human potential, the ideal to strive toward in the absence of divine guidance.

Parts Two and Three deepen the philosophical content and introduce new motifs, such as the eternal recurrence—the notion that all events in life will repeat infinitely in exactly the same way. This is perhaps Nietzsche’s most radical and metaphysically challenging idea. While its literal truth is questionable, Nietzsche’s concern is existential: if one were told that one must live the same life over and over for eternity, could one affirm it joyfully? The concept serves as a test of one’s capacity for embracing life in its totality, including its suffering.

Part Four, written later and not originally intended to be published, is more introspective and melancholic. Zarathustra’s journey becomes more personal, as he confronts disappointment, loneliness, and the realization that his teachings are not being understood. It reflects Nietzsche’s own increasing sense of isolation from the philosophical community and society at large.

The Death of God and Nihilism

The phrase “God is dead” is perhaps Nietzsche’s most misunderstood declaration. It is not an atheistic triumph but a cultural diagnosis. For Nietzsche, modernity has eroded faith in divine order and universal truths. Science, secularism, and rationalism have replaced religious belief, but they have not provided new values or meanings to live by. This void gives rise to nihilism—the belief that life is meaningless.

Zarathustra does not endorse nihilism but sees it as a transitional phase. The death of God is necessary for humanity to grow up, to stop relying on a transcendent authority and instead take responsibility for meaning-making. The tragedy is not that God is dead, but that people still cling to the corpse. They invent new idols—nationalism, science, ideologies, materialism—without facing the deeper crisis of value.

The Übermensch: A New Ideal

The Übermensch represents Nietzsche’s solution to nihilism. This figure is not bound by conventional morality or herd instinct; he is self-creating, self-overcoming, and life-affirming. He accepts suffering, chaos, and contradiction as integral to existence and uses them as raw material for self-transcendence.

Importantly, Nietzsche never provides a detailed blueprint for what the Übermensch looks like. He is more an aspiration than a concrete reality. Zarathustra himself is not the Übermensch, but the prophet who foretells his coming. Nietzsche’s style here is deliberately mythopoetic rather than analytical, as he wishes to inspire transformation rather than explain doctrine.

In contrast to the Übermensch, Nietzsche introduces the Last Man, a figure of passive conformity, comfort, and mediocrity. The Last Man shuns risk, avoids pain, and lives a life of shallow entertainment. In modern terms, he could be seen as the embodiment of consumer culture and complacent materialism. Zarathustra despairs that people prefer the Last Man to the Übermensch because the former is safe and predictable, while the latter is demanding and uncertain.

Eternal Recurrence: Affirmation of Life

The doctrine of eternal recurrence is presented as Zarathustra’s greatest challenge. If one were to live every joy and sorrow over again eternally, would one curse existence or embrace it? To say “yes” to the eternal recurrence is to say “yes” to life itself, without reservation.

This idea serves as a counterpoint to the Christian hope of salvation or escape from suffering. Rather than imagining a better world or an afterlife, Nietzsche insists on radical acceptance of this world, this moment. Eternal recurrence is not about repetition but about affirmation. It demands that one lives as if each moment were eternal, each choice irreversible. In this way, Nietzsche turns metaphysics into a test of ethical courage.

Style, Symbolism, and Irony

Nietzsche’s decision to write Thus Spoke Zarathustra in a prophetic and poetic style is deliberate. He believed traditional academic philosophy was dry, lifeless, and disconnected from real existence. By using aphorisms, parables, and vivid metaphors, Nietzsche aimed to affect not just the intellect, but the spirit and imagination.

The book is saturated with symbolic figures—tightrope walkers, animals, saints, dwarfs, shepherds—each representing philosophical attitudes or existential stages. The tone oscillates between ecstatic joy and deep melancholy. Zarathustra’s journey is both an external mission and an internal odyssey, mirroring Nietzsche’s own philosophical pilgrimage.

Nietzsche also uses irony extensively. Zarathustra’s teachings are often misunderstood by his listeners, just as Nietzsche’s own writings were misinterpreted in his lifetime. This failure of communication becomes a central theme. Zarathustra often withdraws from society, frustrated that his message cannot be heard by the “many.” In this way, the book critiques not only the masses but the difficulty of true philosophical communication.

Legacy and Influence

Thus Spoke Zarathustra has had a profound impact on modern thought, literature, and art. It influenced existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, who grappled with similar questions of meaning, freedom, and absurdity. It inspired writers like Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, and even Richard Strauss, whose symphonic tone poem of the same name immortalized the book’s opening.

However, the work has also been subject to misappropriation and misunderstanding. The Nazis, for example, distorted the Übermensch into a justification for racial superiority—a misuse Nietzsche himself would have abhorred. He despised anti-Semitism, nationalism, and herd ideologies in all forms. Nietzsche’s sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, further corrupted his writings after his mental breakdown, shaping his posthumous reputation in ways he never intended.

Today, Nietzsche is recognized as a profoundly anti-totalitarian thinker who championed individuality, creativity, and the courage to live authentically. Thus Spoke Zarathustra remains a deeply challenging and rewarding read—not because it offers answers, but because it dares readers to question everything, including themselves.

Conclusion

Thus Spoke Zarathustra is not a book to be understood in one sitting. It is to be read, re-read, wrestled with, and lived. It is Nietzsche’s philosophical gospel, his poetic testament to the human potential for greatness in the face of meaninglessness. In Zarathustra, we encounter a prophet not of doom, but of transformation—someone who invites us to overcome not others, but ourselves.

To read Thus Spoke Zarathustra is to confront the possibility of living without illusions, yet with profound affirmation. It is not a work of comfort, but of challenge—an invitation to rise higher, to dance, to become who we are.