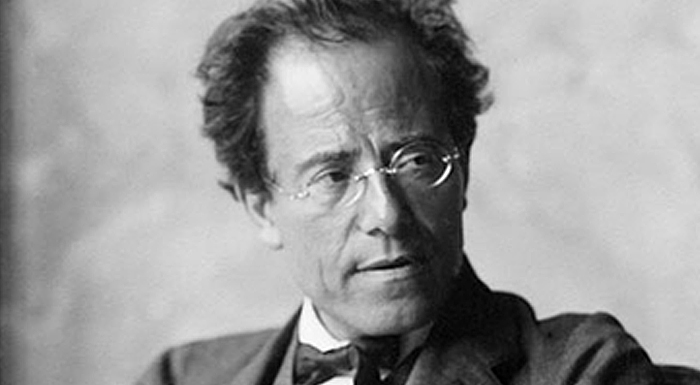

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) was one of the most influential and visionary composers of the late Romantic period. His music, deeply personal and emotionally expansive, bridges the 19th and 20th centuries, embodying both the grand traditions of Austro-German symphonic music and the growing tensions of modernism. Throughout his life, Mahler faced personal struggles, professional challenges, and a world that was rapidly changing around him. Despite these challenges, his symphonies and song cycles have left an indelible mark on the history of Western classical music.

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

Mahler was born on July 7, 1860, in Kaliště, a small village in Bohemia, then part of the Austrian Empire (now in the Czech Republic). He was the second of fourteen children, though only six survived to adulthood. His Jewish heritage and modest upbringing in a German-speaking household exposed him to various cultural influences, which would later shape his music.

From an early age, Mahler exhibited remarkable musical talent. He entered the Vienna Conservatory at the age of fifteen, where he studied composition and piano. His time in Vienna was formative; he absorbed the works of Beethoven, Schubert, and Wagner while developing his own compositional voice. Although he briefly composed in his early years, Mahler’s career initially leaned toward conducting, a profession that would dominate much of his life.

Career as a Conductor

Mahler’s reputation as a conductor grew rapidly. His early posts included positions in regional theaters in Austria and Germany, but his breakthrough came in 1888 when he became the director of the Royal Hungarian Opera in Budapest. His interpretations of Wagner, Mozart, and Beethoven were praised for their intensity and precision.

In 1897, Mahler was appointed director of the Vienna Court Opera, one of the most prestigious musical institutions in Europe. To secure the position, he converted from Judaism to Catholicism—a decision that, though practical, did not shield him from the pervasive antisemitism of the time. His tenure in Vienna was marked by both artistic triumphs and controversies; while he revolutionized opera performance with his meticulous attention to detail, he also faced resistance from conservative factions who resented his reforms.

By 1907, Mahler left Vienna and moved to New York, where he conducted the Metropolitan Opera and later the New York Philharmonic. However, his health was declining, and he eventually returned to Europe, where he died in 1911.

The Symphonist: A Titan of Emotion and Structure

Mahler’s symphonies, ten in total (with the tenth left unfinished), are among the most ambitious and emotionally charged works in the orchestral repertoire. His approach to symphonic form was deeply influenced by Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, particularly in its fusion of vocal and instrumental music. He famously said, “A symphony must be like the world. It must contain everything.” This philosophy is evident in his works, which often juxtapose the sublime and the grotesque, the sacred and the profane.

The First Symphony: “Titan”

Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 in D major, completed in 1888, is an early masterpiece that already demonstrates his unique voice. Inspired by folk music and nature, it incorporates sounds of hunting calls, rustic dances, and even a funeral march based on the children’s song “Frère Jacques” in a minor key. Though it was met with mixed reactions at its premiere, it has since become one of his most popular works.

The “Resurrection” Symphony and the Spiritual Quest

Symphony No. 2, the “Resurrection Symphony,” expands upon Beethoven’s concept of the choral symphony. Written between 1888 and 1894, it deals with themes of death and rebirth, culminating in a triumphant finale that proclaims hope in the afterlife. This work solidified Mahler’s reputation as a symphonist of grand vision and existential depth.

The “Symphony of a Thousand”

One of Mahler’s most ambitious works is his Symphony No. 8, often called the “Symphony of a Thousand” due to its massive orchestration. Premiered in 1910, it combines a setting of the medieval hymn “Veni, Creator Spiritus” with a dramatic adaptation of Goethe’s “Faust.” This symphony represents Mahler at his most transcendent, embracing themes of divine inspiration and redemption.

The Late Symphonies: A Shift Toward Introspection

Mahler’s later symphonies take on a more introspective tone. Symphony No. 9, composed as he battled heart disease, is a deeply personal meditation on mortality, filled with moments of sorrow, nostalgia, and acceptance. The unfinished Symphony No. 10, completed in sketches, further explores these themes, foreshadowing the expressive language of later composers like Alban Berg and Dmitri Shostakovich.

Song Cycles and Lieder

In addition to his symphonies, Mahler composed a significant body of Lieder (songs), many of which are orchestral in scope. His song cycles, such as Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) and Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children), explore themes of love, loss, and existential yearning.

Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), composed between 1908 and 1909, is perhaps his most profound vocal-orchestral work. Combining elements of symphony and song cycle, it sets ancient Chinese poetry to music, contemplating the transience of life and the beauty of the natural world.

Personal Life and Tragedies

Mahler’s personal life was marked by profound tragedy. In 1902, he married Alma Schindler, a composer in her own right. Their marriage was tumultuous, with Alma struggling under Mahler’s dominance and the demands of his career. The loss of their first daughter, Maria, in 1907 was a devastating blow, coinciding with Mahler’s own health problems and his departure from Vienna.

Alma’s affair with architect Walter Gropius further strained their relationship, though she remained by his side during his final years. Mahler’s struggles with antisemitism, professional rivalries, and personal loss deeply influenced his music, imbuing it with a sense of longing and existential depth.

Legacy and Influence

Mahler’s music was not fully appreciated during his lifetime. Critics often found his symphonies too long, too eclectic, or too emotional. However, in the mid-20th century, conductors like Leonard Bernstein championed his works, leading to a Mahler renaissance. Today, his symphonies and song cycles are celebrated as some of the most profound musical achievements of all time.

Mahler’s influence extends beyond classical music. His use of dissonance, orchestration, and psychological depth paved the way for composers like Shostakovich, Britten, and even elements of film music. His symphonies, filled with grand climaxes and intricate counterpoint, continue to resonate with audiences worldwide.

Conclusion

Gustav Mahler was a composer of unparalleled depth and vision. His music, rich with philosophical inquiry and emotional intensity, continues to captivate listeners and musicians alike. As a conductor, he reshaped the opera house; as a composer, he expanded the possibilities of the symphony. More than a century after his death, Mahler remains a towering figure in Western music, a bridge between the past and the future, and a testament to the enduring power of human expression.