The concept of the Von Neumann universal constructor stands as one of the most profound theoretical ideas linking computation, biology, and self-replicating machines. First conceived by the mathematician and polymath John von Neumann in the late 1940s, the universal constructor addresses a fundamental question: Can a machine build any other machine, including itself, given the appropriate instructions? This question touches not only on engineering but also on the nature of life, intelligence, and the limits of automation.

Von Neumann’s work laid the intellectual foundations for modern fields such as artificial life, cellular automata, self-replicating systems, and nanotechnology. Although purely theoretical at the time, the universal constructor remains highly relevant today, especially in discussions about autonomous manufacturing, evolutionary computation, and even ethical concerns surrounding self-replicating technologies.

Historical Context and Motivation

John von Neumann developed the idea of the universal constructor while working on self-reproducing automata, inspired partly by biological systems. At the time, computing machines were large, rigid, and single-purpose. The notion that a machine could reproduce itself seemed almost paradoxical. Yet biological organisms achieve this effortlessly, following encoded instructions stored in DNA.

Von Neumann sought to answer a deeper theoretical challenge: How can a system be complex enough to reproduce itself without logical contradiction? Earlier thinkers had struggled with this problem, as naive self-replication appeared to lead to infinite regress or trivial copying mechanisms.

To resolve this, von Neumann applied formal logic and computation theory, drawing parallels between machines and biological organisms. His goal was not to design a practical self-replicating machine, but to demonstrate that such machines were logically possible.

Definition of the Universal Constructor

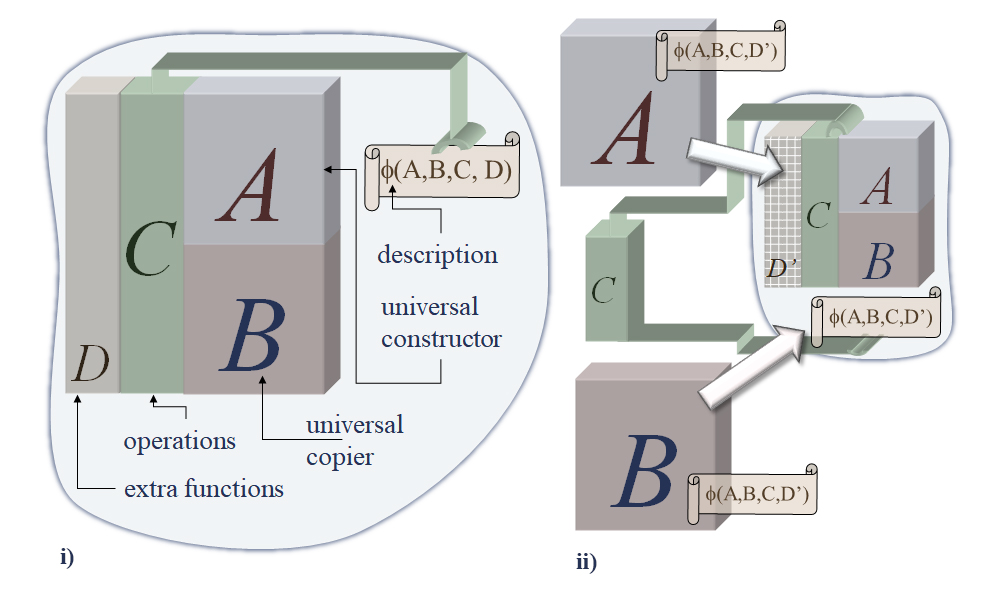

A universal constructor is a machine that can construct any machine, including itself, provided it is supplied with a description (or program) of the machine to be constructed.

More formally, it consists of three core components:

- A constructor mechanism (A)

This is the physical or logical apparatus capable of assembling machines from basic components. - A description or instruction tape (D)

This contains the encoded instructions describing the machine to be built. - A control unit (C)

This interprets the description and directs the constructor mechanism accordingly.

Together, these form a system capable of general construction, analogous to how a universal Turing machine can compute any computable function given the right program.

Self-Replication Without Paradox

One of von Neumann’s most important insights was distinguishing between copying a machine and copying the description of a machine. This mirrors the distinction in biology between proteins and DNA.

In biological systems:

- DNA is copied without being interpreted

- DNA is also interpreted to build proteins

Similarly, in von Neumann’s system:

- The description tape is duplicated directly

- The same description is interpreted to construct a new machine

This separation avoids the paradox of a machine needing to fully understand itself in order to reproduce. Instead, the system simply follows instructions, just as a cell does during reproduction.

This architecture was revolutionary and directly influenced later thinking in genetics, computer science, and systems theory.

Cellular Automata and Implementation

To formalize his ideas, von Neumann implemented the universal constructor using cellular automata (CA)—mathematical models consisting of grids of cells that evolve according to local rules.

Von Neumann’s cellular automaton had:

- A two-dimensional grid

- 29 possible states per cell

- Deterministic update rules

Within this framework, he demonstrated that a universal constructor could exist in principle. Although extremely complex and impractical to build, it proved that self-replication was not forbidden by logic or physics.

Later researchers, notably John Conway, simplified these ideas with systems like the Game of Life, which demonstrated self-replicating and self-constructing patterns using far fewer rules.

Relationship to the Universal Turing Machine

The universal constructor is often compared to the universal Turing machine (UTM), another concept pioneered by early computer scientists.

- A UTM can compute any computable function given the correct program

- A universal constructor can build any constructible machine given the correct description

The key difference lies in domain:

- UTMs operate in the realm of symbolic computation

- Universal constructors operate in the realm of physical or structural construction

However, both rely on the same deep principle: separation of mechanism and description. This idea underpins modern computing architectures, particularly the stored-program computer, which von Neumann also helped invent.

Biological Implications

Von Neumann explicitly acknowledged that biological organisms were the inspiration for his work. In many ways, living cells are universal constructors operating within physical constraints.

DNA acts as:

- A passive description that can be copied

- An active set of instructions when interpreted by cellular machinery

Cells:

- Build proteins

- Repair themselves

- Replicate entirely new organisms

This analogy helped formalize biology in computational terms and influenced later thinkers such as Richard Dawkins, Stuart Kauffman, and researchers in artificial life.

The universal constructor thus provides a bridge between mechanistic biology and information theory, framing life as a process of information-driven construction.

Applications and Modern Relevance

While no true universal constructor exists today, the concept has influenced many modern technologies and research areas.

1. Nanotechnology

Theoretical nanomachines capable of assembling arbitrary structures at the atomic level resemble universal constructors. Molecular assemblers, as proposed by Eric Drexler, are direct descendants of von Neumann’s idea.

2. Autonomous Manufacturing

Self-configuring factories and robotic systems that can manufacture replacement parts for themselves echo universal construction principles.

3. Artificial Life and Evolutionary Systems

Digital organisms in simulations evolve, replicate, and construct increasingly complex structures, guided by encoded descriptions.

4. Space Exploration

Self-replicating machines are often proposed for space colonization, where robots could use local materials to reproduce and build infrastructure without constant human input.

Limitations and Criticisms

Despite its elegance, the universal constructor has notable limitations.

- Physical constraints: Real-world physics imposes limits on what can be constructed and how precisely.

- Error accumulation: Self-replication introduces errors, which can degrade systems over time.

- Control and safety concerns: Unchecked self-replication raises ethical and existential risks, famously discussed in “grey goo” scenarios.

These concerns highlight that while universal constructors are theoretically possible, practical implementations must be tightly constrained.

Philosophical Significance

Beyond engineering, the universal constructor raises profound philosophical questions:

- What distinguishes living systems from machines?

- Is self-replication sufficient for life?

- Can intelligence emerge from purely mechanical processes?

Von Neumann’s work suggests that life is not defined by its material substrate, but by its organizational structure and information flow. This view continues to shape debates in philosophy of mind, artificial intelligence, and systems theory.

Conclusion

The Von Neumann universal constructor remains one of the most ambitious and intellectually rich ideas in the history of science. By demonstrating that self-replicating machines are logically possible, von Neumann reshaped our understanding of computation, life, and construction.

Although still largely theoretical, the universal constructor influences modern research in nanotechnology, artificial life, and autonomous systems. More importantly, it provides a unifying framework that connects machines and organisms under a shared informational paradigm.

In an era increasingly defined by automation and intelligent systems, von Neumann’s insights feel less like abstract speculation and more like a roadmap for the future—one that demands not only technical ingenuity but also philosophical and ethical reflection.