The Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR), opened in 1830, was the world’s first purpose-built passenger and goods railway operated entirely by steam locomotives. Unlike earlier wagonways and industrial railroads, which primarily transported coal or minerals, the L&MR was conceived from the outset as a dual-purpose line: to carry both freight and people between two major cities. Its opening marked the beginning of the modern railway age, transforming commerce, industry, and society not only in Britain but eventually across the world.

This essay will explore the background, construction, opening, and legacy of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, examining why it is regarded as one of the most significant transport projects in human history.

Industrial and Economic Background

In the early nineteenth century, Britain was undergoing the full force of the Industrial Revolution. Factories, powered by steam engines and fuelled by coal, were producing textiles, iron, and manufactured goods in increasing quantities. Lancashire, with Manchester as its industrial hub, was one of the key regions of this transformation.

Manchester, often referred to as “Cottonopolis,” was the centre of the global cotton industry. Raw cotton was imported through the port of Liverpool, spun and woven in Manchester’s mills, and then exported as finished cloth. However, the efficiency of this supply chain was hampered by transportation. The two cities, separated by around 30 miles, were connected only by poor-quality roads and the slow, congested canals. Moving goods by canal could take more than a day and was subject to delays caused by weather and traffic.

By the 1820s, merchants and industrialists in both cities were demanding a faster, more reliable link. The idea of a railway, powered by steam locomotives, began to gain traction. This was a bold proposal, as no such line of this scale and ambition had ever been attempted.

Planning and Authorization

The concept of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was first seriously proposed in 1821. A group of influential businessmen, including Joseph Sandars, a Liverpool corn merchant, and John Kennedy, a Manchester cotton spinner, became leading advocates. They argued that a railway would reduce transport costs, speed up delivery, and improve the competitiveness of their industries.

The plan met resistance, particularly from canal companies and landowners whose property the railway would cross. In 1825, a Parliamentary Bill authorising the railway was rejected, partly because of opposition from landowners such as William Molyneux, 2nd Earl of Sefton.

A revised Bill was introduced in 1826. This time, the promoters employed George Stephenson, who had already gained fame from his work on the Stockton and Darlington Railway. His testimony and the promise of steam locomotion swayed Parliament, and the Act authorising the railway passed. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company was incorporated, and construction began soon afterward.

Construction Challenges

The building of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was a formidable engineering task. The line was to be approximately 31 miles long, running across a variety of landscapes including marshes, embankments, cuttings, and tunnels.

Chat Moss

The most daunting challenge was Chat Moss, a vast bog located between Liverpool and Manchester. At first, critics argued that it was impossible to build a railway across such unstable ground. Stephenson, however, devised a solution: the construction of a floating foundation of heather, brushwood, and earth laid across the bog, with the track built on top. Against the odds, his scheme worked, and the railway across Chat Moss became one of the most celebrated feats of early railway engineering.

Cuttings and Embankments

Elsewhere, huge cuttings and embankments were needed to keep the line as level as possible. One of the most notable was Olive Mount Cutting, near Liverpool, where thousands of tons of sandstone had to be excavated by hand. This was a massive undertaking in an age before mechanical excavators, relying on the labour of hundreds of navvies (navigational engineers).

Tunnels and Bridges

The railway also required several tunnels and bridges. Notable among these was the Wapping Tunnel in Liverpool, nearly two miles long, which provided a direct link between the docks and the railway. It was the first tunnel in the world built under a major city, another engineering milestone.

The total cost of the railway was around £820,000—an enormous sum at the time, equivalent to many tens of millions in today’s money.

Choosing the Motive Power: The Rainhill Trials

One of the critical questions facing the railway’s directors was whether trains should be hauled by fixed stationary engines with cables, or by mobile steam locomotives. Some argued that locomotives were too unreliable for such a long line.

To resolve the debate, the company organised a public competition in October 1829: the Rainhill Trials. Locomotive builders were invited to present their engines, which would be tested on a level track near Rainhill, between Liverpool and Manchester.

Several locomotives competed, but the clear winner was George Stephenson’s Rocket. It combined several key innovations: a multi-tubular boiler for efficient steam generation, a blastpipe to increase draught, and a relatively lightweight design. Rocket reached speeds of up to 30 miles per hour, far exceeding expectations. Its success convinced the company that steam locomotives were the future.

The Rainhill Trials are now remembered as a pivotal moment in transport history. They set the technological template for locomotive design for decades to come.

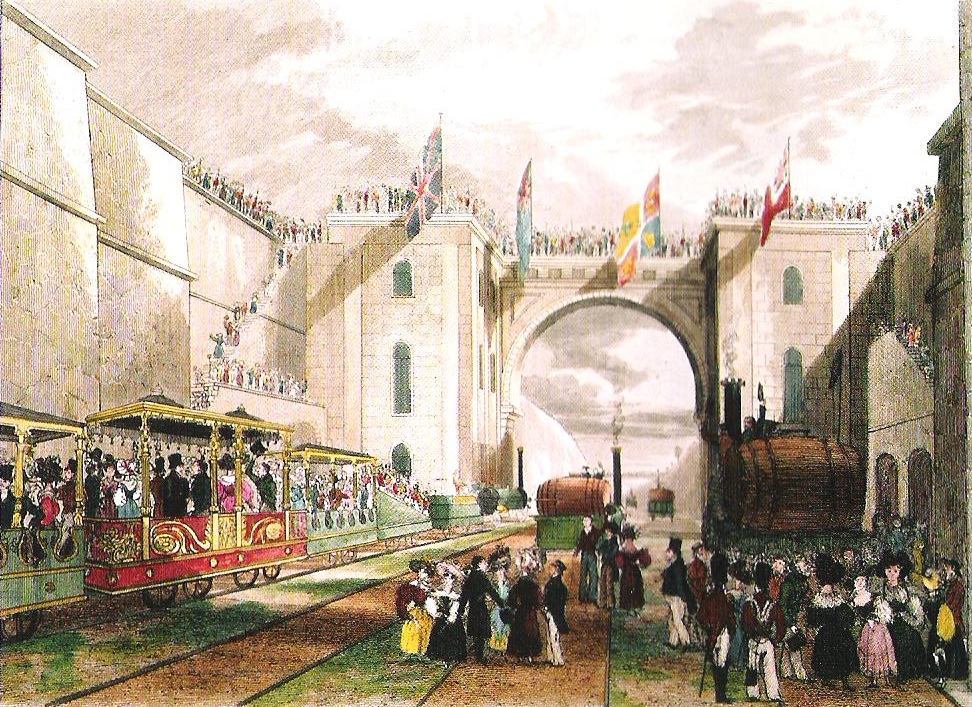

The Grand Opening: September 15, 1830

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was formally opened on 15 September 1830, amid enormous public excitement. Dignitaries, including the Duke of Wellington (then Prime Minister), attended the ceremony. A procession of eight locomotives hauled trains carrying hundreds of passengers along the new line.

Tragically, the day was marred by the death of William Huskisson, Member of Parliament for Liverpool. While attempting to speak with the Duke of Wellington at Parkside station, Huskisson accidentally stepped onto the track and was struck by Stephenson’s Rocket. He suffered severe injuries and later died, becoming the first widely reported casualty of a railway accident.

Despite this sombre incident, the opening of the railway was hailed as a triumph of engineering and modernity. It was the first time that a major railway had been designed and built for regular passenger and goods service, powered entirely by locomotives.

Early Operations

The L&MR quickly proved its worth. Passenger demand was far higher than anticipated, with people flocking to experience the novelty of travelling at unprecedented speeds. For ordinary workers and travellers, the railway dramatically reduced the time taken to move between Liverpool and Manchester—from many hours by road or canal to about 90 minutes by train.

Freight traffic was also significant. Cotton, raw materials, and manufactured goods could be moved more quickly and cheaply than ever before, strengthening the economic link between the port and the industrial heartland.

The railway introduced many features that became standard in later systems:

- Timetabled passenger services.

- First- and second-class carriages, establishing distinctions in comfort and price.

- Railway stations, such as Crown Street in Liverpool and Liverpool Road in Manchester, both of which became pioneering passenger terminals.

Wider Impact

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway had a profound influence far beyond its immediate route. It proved that steam locomotives could operate a reliable, large-scale service for both goods and passengers.

Other railway projects quickly followed, inspired by its success. Within a decade, a network of railways was spreading across Britain. By mid-century, railways had become the backbone of industrial transport, carrying coal, raw materials, finished goods, and millions of passengers.

The impact was not merely economic. Railways transformed social life. They made travel faster, cheaper, and more accessible, enabling people to commute, take leisure trips, and visit distant relatives. They helped to standardise time (with the introduction of “railway time”), reshaped landscapes, and spurred urban growth.

Globally, the L&MR set the model for railway development. From continental Europe to North America, engineers and entrepreneurs adopted the principles first demonstrated in Lancashire. The modern age of railways, which would span continents and accelerate globalisation, began with the Liverpool and Manchester line.

Legacy and Preservation

Today, the legacy of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway is celebrated as one of the great achievements of the Industrial Revolution. Parts of the original infrastructure remain. The Liverpool Road station in Manchester, now preserved as part of the Science and Industry Museum, is the world’s oldest surviving passenger railway station. The Wapping Tunnel still exists, though no longer in use. Sections of the original alignment are still part of the modern railway network.

In 1980, the 150th anniversary of the railway was commemorated with events, including the restoration of working replicas of Stephenson’s Rocket. In 2020, the 190th anniversary was marked, though in a more subdued fashion due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 200th anniversary in 2030 is expected to be a major national event, highlighting once again the railway’s transformative impact.

Conclusion

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was far more than a regional transport project. It was the prototype of the modern railway system: a fully steam-powered, passenger-and-freight line built to a consistent standard. Its construction overcame immense engineering challenges, its opening captured the imagination of the public, and its success transformed industry, society, and global transport.

From the bogs of Chat Moss to the triumph of the Rainhill Trials, the story of the L&MR is one of innovation, perseverance, and vision. It stands as a monument to the ingenuity of early nineteenth-century Britain and the individuals—George Stephenson chief among them—who dared to imagine a new way of moving people and goods.

Nearly two centuries later, the world’s vast networks of railways, from high-speed trains in Europe and Asia to freight systems spanning continents, can all trace their lineage back to the modest 31-mile line between Liverpool and Manchester.