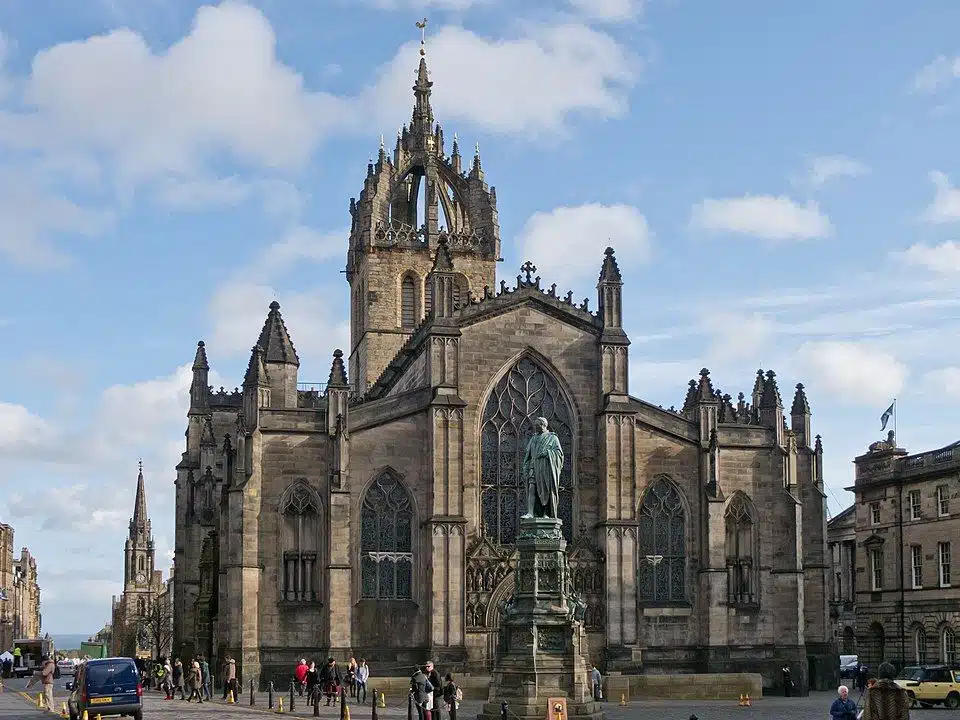

At the centre of Edinburgh’s historic Royal Mile, standing between Edinburgh Castle and the Palace of Holyroodhouse, rises the unmistakable crown spire of St Giles’ Cathedral—officially known as the High Kirk of Edinburgh. For nearly nine centuries, St Giles has been a focal point of the city’s religious, political, and cultural life. It is not only a place of worship but also a symbol of Scottish identity, resilience, and reform.

Origins and Early History

The precise origins of St Giles’ Cathedral are somewhat obscure. Tradition holds that a church was established on the site around 1124, during the reign of King David I, who was renowned for founding many religious houses across Scotland. The church was dedicated to St Giles, the patron saint of lepers, cripples, and outcasts. This dedication may reflect Edinburgh’s early character as a bustling medieval burgh, where disease and poverty were as much a part of daily life as commerce and politics.

The first church was a simple Romanesque building, modest compared to the grand cathedrals of England and Europe. Nevertheless, it quickly became an important parish church for the growing burgh of Edinburgh.

Destruction and Rebuilding

Like much of medieval Scotland, St Giles was subject to violence and upheaval. In 1385, during the Hundred Years’ War, the English army under Richard II invaded Scotland and burned much of Edinburgh, including St Giles’ Church.

The church was soon rebuilt, this time in the Gothic style that remains visible today. The reconstruction gave the building its characteristic pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and stained-glass windows. Over the following centuries, the structure was expanded piecemeal, resulting in a complex and irregular layout that reflects its turbulent history.

The Crown Spire

The most distinctive feature of St Giles is its crown spire, added around 1495. This open-work crown of stone, supported on flying buttresses, rises 161 feet (49 m) above the city. The spire is both functional and symbolic: a marker of civic pride, a guide for travelers approaching Edinburgh, and a lasting emblem of the city’s skyline.

It is one of only a handful of such spires in Europe, with parallels in St Nicholas’ Kirk in Aberdeen and King’s College Chapel in Cambridge. For many, the crown spire represents Edinburgh as powerfully as the Castle or Arthur’s Seat.

St Giles and the Scottish Reformation

The sixteenth century transformed St Giles from a medieval Catholic church into the spiritual heart of Presbyterian Scotland. In 1559, fiery Protestant reformer John Knox preached in St Giles, igniting passions that culminated in the Scottish Reformation.

St Giles became Knox’s base as he battled against what he saw as corruption in the Catholic Church and fought to establish a new Protestant order. From its pulpit, Knox denounced idolatry, the Mass, and the influence of Mary, Queen of Scots. His sermons were so forceful that they are said to have shaped the character of Scottish Presbyterianism: austere, disciplined, and fiercely independent.

During this period, the church was physically altered to suit its new role. Statues and altars were removed or destroyed, and the building was partitioned into separate spaces for different congregations, civic meetings, and even a prison. At one point, the church was divided into as many as four separate kirks, reflecting the practical needs of the parish and the city.

Civic and Political Role

St Giles has always been more than a religious building—it has also served as Edinburgh’s civic heart. For centuries, the churchyard was the site of markets, proclamations, and public punishments. The Tolbooth, Edinburgh’s town hall and prison, stood next to the church until it was demolished in the 19th century, further cementing the connection between St Giles and the governance of the city.

Inside, the church hosted important civic ceremonies, including the annual Riding of the Parliament—when Scotland’s lawmakers would process from the church to Parliament House. The church thus became closely associated with Scottish nationhood and independence.

The 17th Century: Tumult and Tradition

In 1637, St Giles once again became the flashpoint of national religious upheaval. King Charles I, seeking to impose Anglican practices on Scotland, introduced a new prayer book. The first public reading of this liturgy at St Giles was met with fury. According to legend, a market trader named Jenny Geddes hurled her stool at the minister, sparking a riot that spread across the country.

This event contributed to the signing of the National Covenant in 1638, a defining moment in Scottish history. The Covenant rejected royal interference in the church and asserted Presbyterian governance. Copies of the document were signed in St Giles, making it a cradle of resistance and independence.

Architecture and Interior

Despite centuries of alterations, the architectural core of St Giles remains Gothic. Its irregular plan includes a central nave, transepts, and multiple chapels, reflecting its piecemeal construction.

The Thistle Chapel

One of the most striking features of the interior is the Thistle Chapel, built in 1911 to house the Order of the Thistle, Scotland’s highest order of chivalry. Designed by architect Robert Lorimer, the chapel is a masterpiece of Gothic Revival craftsmanship, with intricately carved oak stalls, heraldic crests, and vaulted stonework. It provides a striking contrast to the more austere Presbyterian tradition of the main church.

Stained Glass

Although most medieval glass was destroyed during the Reformation, the Victorian era saw a revival of stained glass at St Giles. The windows depict biblical scenes, saints, and figures from Scottish history, blending devotion with national pride.

Monuments and Memorials

The church houses numerous monuments, including memorials to John Knox, James Graham, the Marquis of Montrose, and later figures such as writers Robert Louis Stevenson and Robert Burns. In this way, St Giles serves as a kind of Scottish pantheon, commemorating the nation’s heroes and thinkers.

The 19th Century Restoration

By the 19th century, centuries of use and neglect had left St Giles in poor condition. The city embarked on a major restoration under the guidance of architect William Burn, and later William Chambers, the Lord Provost of Edinburgh.

The aim was to unify the building, removing the internal divisions and restoring its dignity as the city’s principal church. The restoration was controversial, as many alterations erased post-Reformation features, but it also gave St Giles much of its current appearance.

Modern Role

Today, St Giles’ Cathedral continues as an active place of worship within the Church of Scotland. It hosts regular services, including those attended by the Scottish Parliament and other civic bodies. The building also serves as a venue for concerts, lectures, and events during the Edinburgh Festival.

Tourists flock to admire its architecture and history, while locals still see it as a place of gathering and remembrance. Its central location on the Royal Mile makes it a natural stopping point for anyone exploring Edinburgh’s Old Town.

Symbol of National Identity

St Giles remains a potent symbol of Scottish identity. It is a place where religion, politics, and culture intersect. Its association with John Knox and the Reformation, the National Covenant, and the struggles for independence and self-determination give it a resonance that transcends architecture.

When Scotland regained a devolved parliament in 1999, ceremonies at St Giles reminded the world of its historical role as the spiritual heart of the nation. Its crown spire continues to dominate Edinburgh’s skyline, reminding citizens and visitors alike of the city’s deep roots.

Conclusion

St Giles’ Cathedral is far more than a church; it is the story of Edinburgh itself, embodied in stone, glass, and memory. From its humble beginnings in the 12th century, through destruction, Reformation, and restoration, it has endured as the heart of the city’s spiritual and civic life.

It was here that John Knox thundered against tyranny, that the Covenant was signed, that markets bustled in its shadow, and that Scotland’s highest order of chivalry still gathers. Its crown spire stands as a beacon of resilience and pride, symbolizing a people who have endured wars, reformations, and upheavals while never losing sight of their identity.

In its architecture, memorials, and traditions, St Giles tells the story of a nation—its struggles for freedom, its devotion to faith, and its enduring creativity. To step inside St Giles is to step into the living heart of Scotland.