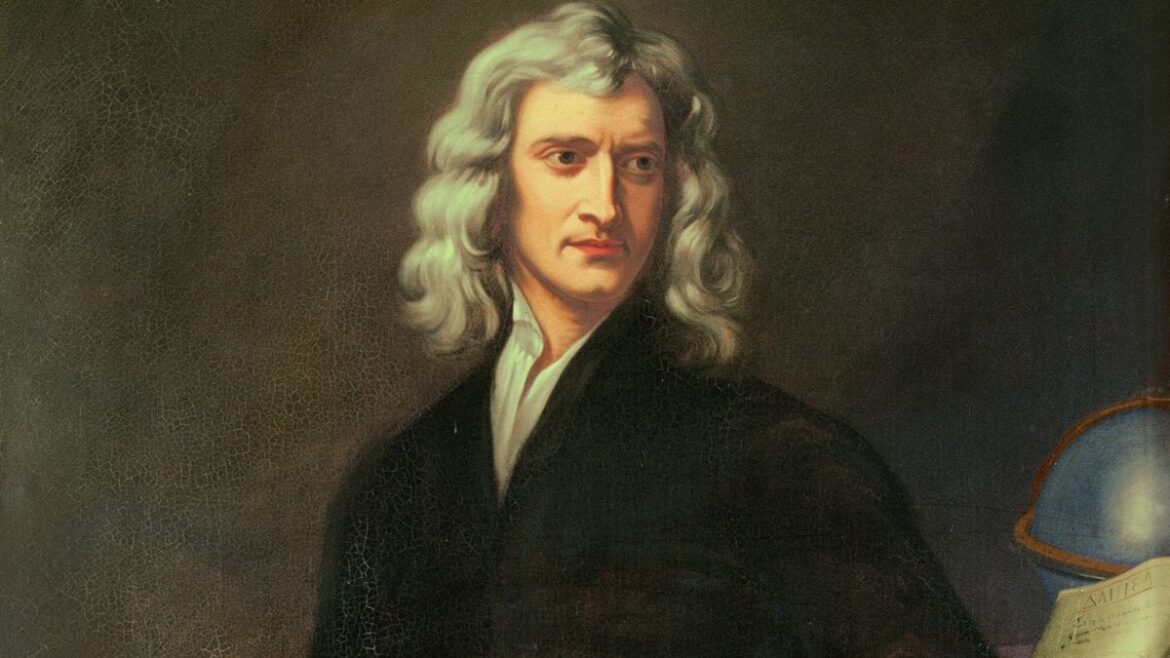

Sir Isaac Newton, born on January 4, 1643 (December 25, 1642, Old Style calendar), in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England, is one of the most influential figures in the history of science. Renowned for his work in mathematics, physics, astronomy, and natural philosophy, Newton’s discoveries laid the foundation for classical mechanics and profoundly changed humanity’s understanding of the universe. His intellect, curiosity, and perseverance propelled him to formulate laws that would dominate scientific thinking for centuries.

Early Life and Education

Newton was born prematurely and was not expected to survive. His father, also named Isaac Newton, died three months before his birth. When Newton was three years old, his mother remarried and left him in the care of his grandparents. These early experiences of abandonment and isolation may have contributed to Newton’s intense personality and single-minded focus in his academic pursuits.

He attended the King’s School in Grantham, where he demonstrated an early talent for mechanics and mathematics. In 1661, he was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge. Initially, Newton was not a standout student, but he immersed himself in the study of classical philosophers as well as the latest scientific works of Galileo, Descartes, and Kepler.

It was during the years 1665–1667, when the university temporarily closed due to the Great Plague, that Newton returned to Woolsthorpe and entered a period of intense intellectual development. This time is often referred to as Newton’s “Annus Mirabilis” or “Year of Wonders,” during which he developed many of the fundamental concepts that would later make him famous.

Major Contributions

1. Mathematics: The Development of Calculus

Newton made groundbreaking advancements in mathematics, most notably the development of calculus, which he referred to as “the method of fluxions.” Calculus allowed for the computation of changing quantities and became a critical tool for future developments in physics and engineering. Although Newton developed these ideas around the same time as German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the two entered into a bitter dispute over who discovered calculus first. Modern historians recognize that both men developed calculus independently.

2. Physics: Laws of Motion and Universal Gravitation

Newton’s most renowned work is the “Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica” (commonly referred to as the Principia), published in 1687. In this seminal book, Newton outlined three fundamental laws of motion:

- First Law (Law of Inertia): An object at rest will remain at rest, and an object in motion will remain in uniform motion unless acted upon by a force.

- Second Law: The acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force acting on it and inversely proportional to its mass (F = ma).

- Third Law: For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

These laws established the framework for classical mechanics, which remained the dominant paradigm in physics until the 20th century.

Newton also formulated the Law of Universal Gravitation, which posited that every mass attracts every other mass with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. This law explained not only the motion of falling objects on Earth but also the motion of celestial bodies, such as planets and moons.

3. Optics: Nature of Light and Color

In addition to his work in mechanics and mathematics, Newton made significant contributions to optics. He conducted experiments with prisms and discovered that white light is composed of a spectrum of colors. By refracting sunlight through a prism, he demonstrated that light could be split into a rainbow of colors and then recombined into white light, challenging the prevailing view that white light was pure and homogeneous.

Newton also built the first practical reflecting telescope, known as the Newtonian telescope, which used a curved mirror to eliminate chromatic aberration—a common problem in refracting telescopes of the time. This invention enhanced the quality of astronomical observations and is still used in many modern telescopes.

Later Life and Career

Newton held several prestigious positions in his lifetime. In 1669, at the age of 26, he was appointed Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, a position later held by Stephen Hawking. In 1696, he moved to London to take up the role of Warden of the Royal Mint, and later, Master of the Mint, where he oversaw the modernization of British coinage and implemented anti-counterfeiting measures. His role at the Mint was not ceremonial—he took it seriously, personally interrogating counterfeiters and improving the quality of the currency.

In 1703, Newton became President of the Royal Society, a position he held until his death. In 1705, he was knighted by Queen Anne, becoming Sir Isaac Newton.

Personality and Philosophical Outlook

Newton was known for his intense focus and solitary nature. He was meticulous, secretive, and sometimes quarrelsome. He engaged in several disputes with other scientists, not just Leibniz but also Robert Hooke, over matters of priority and credit. Despite this, his commitment to empirical observation and logical reasoning set new standards for scientific inquiry.

While he is best remembered for his scientific achievements, Newton also delved deeply into alchemy, theology, and biblical chronology. He wrote extensively on these subjects, although much of his work remained unpublished during his lifetime. Newton believed that science and religion were not mutually exclusive but rather complementary paths to understanding the universe.

Legacy

Isaac Newton’s legacy is profound and far-reaching. His laws of motion and universal gravitation unified the heavens and the Earth under a single theory of motion. His mathematical methods revolutionized analysis, and his experimental techniques in optics advanced the scientific method. Newton’s work laid the groundwork for the Enlightenment, fueling scientific progress and rational thought.

Albert Einstein, whose theory of relativity would eventually supersede Newton’s in explaining phenomena at very high speeds and gravitational fields, once remarked, “Newton, forgive me.” This humble acknowledgment underscores Newton’s towering contributions.

Even today, Newton’s influence is felt in education, science, and engineering. His principles are taught in classrooms around the world and continue to guide our understanding of motion and force in everyday life.

Conclusion

Sir Isaac Newton remains a monumental figure in the annals of science. His relentless pursuit of knowledge and commitment to empirical inquiry transformed not only the field of physics but also the broader trajectory of human understanding. From the falling apple to the movements of the planets, Newton’s insights revealed a cosmos governed by law, order, and reason. More than 300 years after the publication of Principia, the name Isaac Newton is still synonymous with genius, discovery, and the enduring power of the human mind.