The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest known pieces of literature, dating back to ancient Mesopotamia around 2100 BCE. This epic poem, which originated from Sumerian oral traditions and later Akkadian and Babylonian texts, tells the story of Gilgamesh, a legendary king of Uruk, and his quest for glory, friendship, and ultimately, immortality. The tale has influenced many later literary and mythological traditions, and its themes of heroism, mortality, and the meaning of life remain relevant today.

Historical Context and Origins

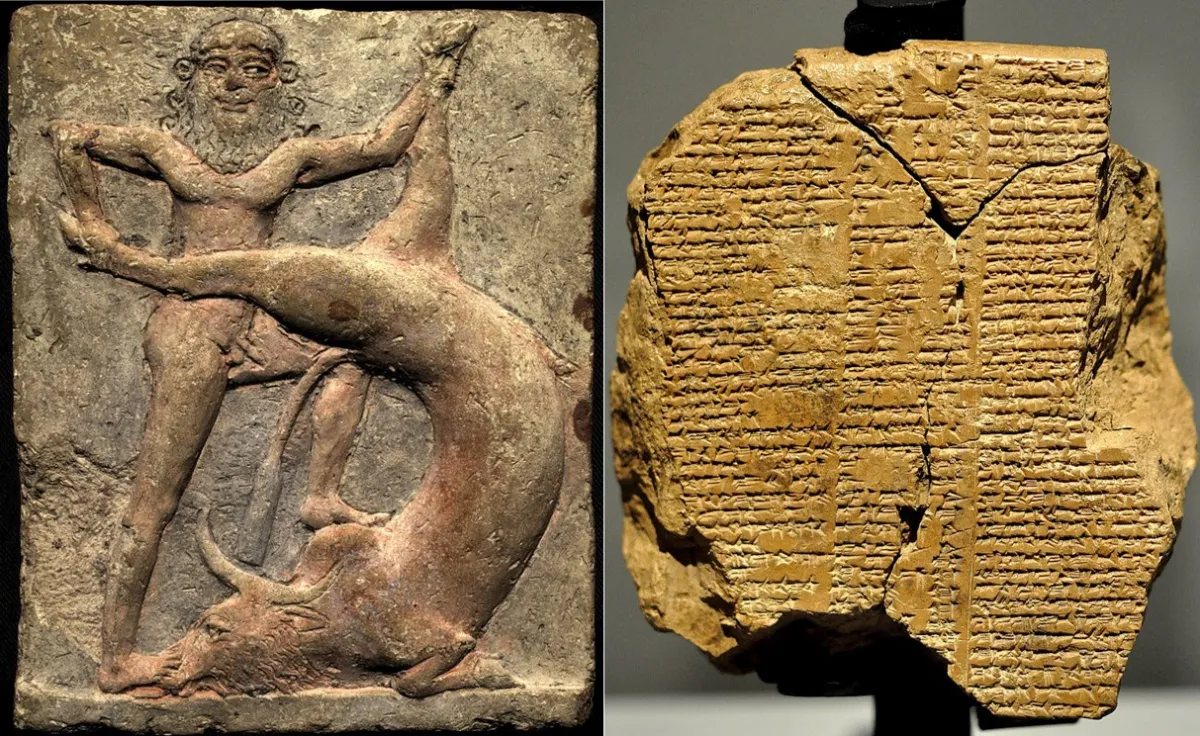

The story of Gilgamesh is found inscribed on twelve clay tablets written in cuneiform script. The most complete version of the epic was discovered in the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in Nineveh (7th century BCE), but earlier fragments of the story date back much further, to Sumerian sources around 2100 BCE.

Gilgamesh was a historical king of Uruk, a Sumerian city-state located in present-day Iraq. Scholars believe he ruled sometime around 2700 BCE, though his existence is still debated. Over time, his exploits were mythologized, and he became a demigod in Sumerian and later Akkadian mythology. The stories of Gilgamesh evolved, incorporating influences from different Mesopotamian cultures, particularly the Babylonians.

The Plot of the Epic

The Epic of Gilgamesh is structured into distinct episodes, each exploring different aspects of human nature and the struggle between civilization and nature, power and responsibility, and the acceptance of mortality.

Gilgamesh, the Tyrant King

The epic begins by describing Gilgamesh as a powerful but oppressive king. He is described as two-thirds god and one-third human, making him physically strong but also prone to arrogance. His excessive rule leads the people of Uruk to pray for relief, and in response, the gods create Enkidu, a wild man, to challenge him.

Enkidu’s Transformation and Friendship with Gilgamesh

Enkidu, raised among animals, represents the natural world. When he encounters a temple prostitute named Shamhat, he is introduced to human ways—clothing, food, and companionship—symbolizing his transition from the wild to civilization. He travels to Uruk, where he confronts Gilgamesh, and after an intense battle, the two become best friends, marking the beginning of an epic companionship.

The Journey to Slay Humbaba

Seeking adventure, Gilgamesh and Enkidu set out to the Cedar Forest to confront Humbaba, a monstrous guardian appointed by the gods. With the blessing of the sun god Shamash, they slay Humbaba, but in doing so, they anger the gods. This quest establishes Gilgamesh as a mighty warrior, but it also foreshadows the consequences of defying the divine order.

The Wrath of the Gods and Enkidu’s Death

After their victory, the goddess Ishtar attempts to seduce Gilgamesh. When he rejects her, she sends the Bull of Heaven to punish him. Together, Gilgamesh and Enkidu slay the bull, but this final act of defiance proves costly. The gods decree that Enkidu must die as punishment.

Enkidu’s death devastates Gilgamesh, marking a turning point in his character. For the first time, he is confronted with the reality of mortality, and he becomes obsessed with finding a way to escape death.

Gilgamesh’s Quest for Immortality

Determined to find eternal life, Gilgamesh embarks on a perilous journey to find Utnapishtim, the Mesopotamian equivalent of Noah, who survived a great flood and was granted immortality by the gods.

His journey takes him across treacherous landscapes, including the waters of death and the mountains of Mashu, where he encounters scorpion-men and the tavern keeper Siduri, who advises him to accept life as it is. However, Gilgamesh persists and eventually meets Utnapishtim.

The Flood Myth and the Lesson of Mortality

Utnapishtim recounts the great flood, a story strikingly similar to the biblical story of Noah’s Ark. He explains that immortality was a unique gift from the gods and that humans were not meant to escape death. Nevertheless, he offers Gilgamesh a test: if he can stay awake for six days and seven nights, he will prove himself worthy of eternal life. Gilgamesh fails the test, revealing the limits of human endurance.

Utnapishtim then tells him about a plant that grants rejuvenation, which Gilgamesh retrieves, only to have it stolen by a serpent, symbolizing the inevitability of death. This moment reinforces the theme that mortality is inescapable, and humans must find meaning in their mortal existence.

Gilgamesh’s Return and Wisdom

Defeated yet wiser, Gilgamesh returns to Uruk, recognizing the greatness of his city and the importance of his legacy. He understands that while he cannot achieve physical immortality, his deeds and the civilization he has built will endure.

Themes in the Epic of Gilgamesh

The epic is rich with themes that resonate across time and cultures:

1. The Quest for Immortality

Gilgamesh’s journey mirrors humanity’s struggle with mortality. His failed search for eternal life ultimately teaches him to embrace his humanity and appreciate the time he has.

2. Friendship and Transformation

The bond between Gilgamesh and Enkidu is central to the story. Their friendship transforms both characters, with Gilgamesh learning compassion and Enkidu discovering civilization.

3. Civilization vs. Nature

Enkidu represents nature, while Gilgamesh embodies civilization. Their friendship bridges these two worlds, but their journey also explores the tension between humanity’s wild origins and its desire to create order.

4. Divine Will and Human Limits

The gods play a significant role, demonstrating their control over fate. Gilgamesh’s defiance against them leads to suffering, illustrating the limits of human ambition.

5. The Importance of Legacy

By the end of the epic, Gilgamesh realizes that true immortality lies in the impact one leaves behind, whether through deeds, wisdom, or contributions to society.

Influence and Legacy of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh has influenced numerous cultures and literary traditions. Many elements, such as the flood story, appear in the Bible, Greek mythology, and later epics like Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

Modern interpretations see Gilgamesh as a universal figure, representing humanity’s struggle with life’s fundamental questions. His journey is often compared to Joseph Campbell’s “Hero’s Journey,” making it a cornerstone of mythology and storytelling.

Conclusion

The Epic of Gilgamesh is not just the world’s first great literary work; it is a timeless exploration of what it means to be human. Through friendship, adventure, loss, and wisdom, Gilgamesh’s journey reflects universal truths about mortality, the search for meaning, and the acceptance of human limitations. Even after thousands of years, his story continues to inspire, reminding us that while life is fleeting, the impact we leave behind endures.