Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket is one of the most chilling and intellectually haunting war films ever made. Released in 1987, it presents the Vietnam War not through the lens of heroism or patriotism, but through the transformation—and ultimately the destruction—of human identity. Kubrick’s masterpiece dissects the process by which men are stripped of individuality, turned into soldiers, and then thrust into a world where morality, reason, and humanity collapse under the weight of violence and survival.

Unlike most war films that focus on the battlefield, Full Metal Jacket begins at the very root of the problem: the systematic conditioning of young recruits. It is a film in two distinct halves—first, the brutal training grounds of Parris Island, and second, the chaos of the Vietnam War itself. Together, these halves create a disturbing portrait of how institutions mold men into instruments of death and how those same men struggle to reconcile their humanity within the machinery of war.

The First Half: The Making of a Soldier

The film opens with a series of recruits having their heads shaved, their identities literally stripped away. The sound of the electric razor whirs like a mechanical prelude to dehumanization. The recruits have been reduced to identical heads—blank slates ready to be rewritten by the Marine Corps.

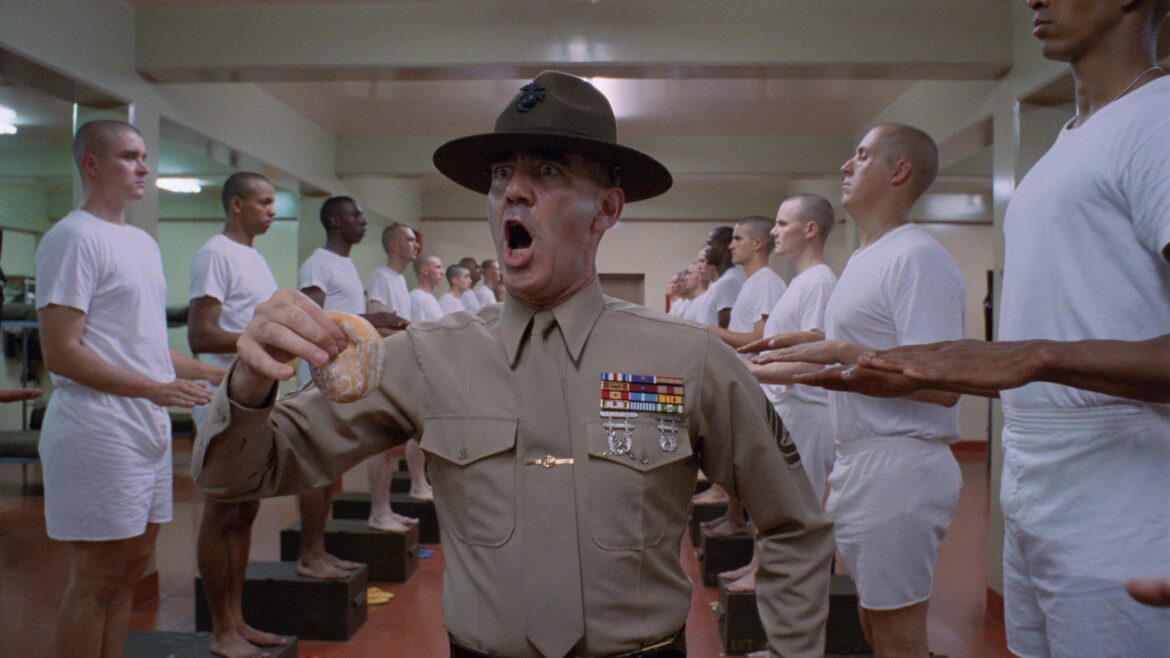

Enter Gunnery Sergeant Hartman (R. Lee Ermey), one of cinema’s most iconic characters. Hartman is both terrifying and fascinating, a whirlwind of insults, commands, and psychological manipulation. His job is clear: to break the men down so completely that they cease to think of themselves as individuals. “You are nothing but unorganized grabasstic pieces of amphibian sh*t,” he bellows. His verbal abuse is relentless, designed to obliterate weakness and build obedience.

Kubrick’s camera captures this world with cold precision. The barracks are symmetrical, sterile, and stripped of personality. Every frame reinforces the sense of order imposed upon chaos. The recruits are not learning to think—they are learning to obey. And in that obedience, they are losing the very qualities that make them human.

Among the recruits, two stand out: Private Joker (Matthew Modine), who retains a sense of irony and intelligence, and Private Leonard Lawrence (Vincent D’Onofrio), nicknamed “Private Pyle.” Joker is sharp and observant, representing the rational mind that questions authority, while Pyle is slow, clumsy, and vulnerable—the perfect target for Hartman’s cruelty.

At first, Pyle tries to follow the rules, but his lack of coordination and emotional fragility make him an outcast. The more he fails, the more Hartman and the other recruits punish him. What begins as “tough love” quickly escalates into psychological torture. In a harrowing sequence, the platoon holds him down in the barracks and beats him with bars of soap wrapped in towels. It’s a turning point—Pyle’s breaking moment.

After that, something in him changes. He becomes eerily calm, robotic, and unnervingly efficient. He learns to shoot perfectly. His face, once anxious and childlike, turns blank and distant. Hartman’s methods have succeeded—Pyle has been transformed into a Marine. But at what cost?

The cost becomes clear in the film’s first act climax. In one of Kubrick’s most chilling scenes, Pyle sits on his bunk in the middle of the night, cleaning his rifle and muttering the Marine Corps Rifleman’s Creed: “This is my rifle. There are many like it, but this one is mine.” Joker finds him in the latrine, his face illuminated by harsh fluorescent light, his voice eerily monotone. When Hartman confronts him, Pyle snaps, shoots Hartman, and then turns the gun on himself.

The gunshot echoes through the empty barracks—a symbol of the institution devouring its own creation. Pyle’s suicide is the inevitable outcome of total dehumanization. The Marine Corps has built a perfect soldier—obedient, efficient, and utterly detached from empathy—and in doing so, it has destroyed the man who once inhabited that uniform.

The Second Half: The Battlefield of Vietnam

The film’s second half shifts abruptly to Vietnam, where Joker is now a combat correspondent for Stars and Stripes, the military newspaper. The tone and setting change dramatically, but the psychological themes remain. The boot camp may be over, but the dehumanization continues.

Joker’s job is to report on the war, but his writing is filtered through military censorship. He’s expected to produce propaganda that maintains morale. His trademark helmet—scrawled with the words “Born to Kill” alongside a peace button—captures the film’s central irony. Joker represents the divided soul of the modern soldier: part killer, part philosopher, caught between humanity and duty.

Kubrick’s Vietnam is not lush and cinematic like Apocalypse Now. It is dusty, bleak, and artificial—a wasteland of rubble and ruin. The war is depicted as chaotic, meaningless, and devoid of glory. The soldiers banter about prostitutes and death, oscillating between dark humor and existential despair.

When Joker joins a squad led by the cynical Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin), he encounters the reality of combat for the first time. The film’s dialogue is laced with gallows humor and vulgarity, but beneath it lies an emptiness—a sense that none of them truly understand why they’re there. The soldiers are fighting not for victory or ideology but for survival and camaraderie.

The turning point comes during the battle for Hue City, a sequence shot with Kubrick’s trademark meticulousness. The soldiers move through bombed-out buildings, smoke, and corpses, hunted by an unseen sniper. The tension is unbearable. When they finally corner the sniper, they discover it’s a young Vietnamese girl, barely more than a child. She’s wounded and dying, gasping for mercy.

The men stand over her, unsure what to do. Animal Mother wants to leave her, but Joker volunteers to end her suffering. His act of mercy is also an act of killing—compassion and violence fused into one. When he pulls the trigger, his transformation is complete. The young idealist from boot camp has become what the system intended: a soldier who can kill without hesitation.

The final scene, as the soldiers march through the smoking ruins singing the Mickey Mouse Club theme song, is both absurd and tragic. It’s a surreal reminder that these are still boys—boys who have been taught to kill and laugh at death. The childlike song underscores the horror of their lost innocence.

The Meaning of Dehumanization

Kubrick’s brilliance lies in his ability to reveal the mechanics of violence. Full Metal Jacket doesn’t glorify war or pity its participants—it dissects them. The first half shows how the military machine conditions the human mind; the second half shows how that conditioning manifests in the chaos of war.

The title itself is symbolic. A “full metal jacket” refers to a bullet casing, but it also represents the psychological armor that soldiers must wear to survive. Humanity is a liability; emotion is weakness. The film is filled with moments that reflect this transformation—soldiers speaking in mechanical tones, joking about corpses, or treating death as entertainment.

Kubrick suggests that the real enemy is not the Viet Cong but the process of militarization itself. The recruits are told that killing is necessary, that compassion is dangerous. Hartman doesn’t just train killers—he manufactures them. By the end of the film, the soldiers are indistinguishable from the machines that fire their weapons.

Joker’s internal conflict—his peace badge versus his “Born to Kill” helmet—embodies the paradox of modern warfare. The soldiers are human beings forced to suppress their humanity in order to function. Yet, as Kubrick implies, the cost of that suppression is the destruction of the soul.

Kubrick’s Vision and Style

Visually, Full Metal Jacket is pure Kubrick: symmetrical compositions, long tracking shots, and a clinical detachment that heightens the horror. Every shot is deliberate, every frame composed to evoke unease. The film’s realism is heightened by its artificiality—Vietnam was recreated on an abandoned industrial site in England, giving the war a surreal, dreamlike quality.

The performances are extraordinary. R. Lee Ermey, a real-life drill instructor, delivers a performance that is both terrifying and hypnotic. His dialogue—partly improvised—is a torrent of insults and precision. D’Onofrio’s transformation from timid recruit to deranged killer is unforgettable, while Modine’s understated performance gives the film its emotional center.

Kubrick’s use of music is also masterful. Classic rock songs like “Surfin’ Bird” and “Paint It Black” contrast violently with the film’s grim visuals, highlighting the absurdity of war’s normalization. The cheerful tunes become ironic soundtracks to human suffering, emphasizing how pop culture trivializes violence.

Legacy and Interpretation

Full Metal Jacket is often compared to Apocalypse Now and Platoon, but it stands apart in its cold, analytical approach. Where Oliver Stone’s Platoon is emotional and confessional, Kubrick’s film is detached and philosophical. It doesn’t ask the viewer to feel sympathy—it asks them to think.

The film’s impact on war cinema is enormous. Its portrayal of boot camp influenced countless films and series that followed, from Jarhead to Band of Brothers. More importantly, it forced audiences to confront an uncomfortable truth: that war is not just fought on battlefields—it’s engineered in training camps, in minds, and in cultures that glorify violence.

Conclusion: The Hollow Core of War

By the time Full Metal Jacket ends, there are no heroes—only survivors. The soldiers march through ruins singing like children, their innocence long gone, their humanity reduced to echoes. The film closes not with triumph but with emptiness.

Kubrick doesn’t condemn his characters—he condemns the system that made them. The film is both an anti-war statement and a psychological study of how institutions can turn human beings into instruments of destruction. It’s not just about Vietnam—it’s about the timeless machinery of war itself.

In the end, Full Metal Jacket leaves us with a chilling realization: beneath the uniform, beneath the discipline and bravado, there remains a human being—fragile, fearful, and forever scarred by what they have become.