The locomotive Blücher, built in 1814 by George Stephenson, occupies a crucial place in the early history of railway engineering. While not the first steam locomotive ever constructed, it was Stephenson’s very first attempt at building one, and it set him on the path to becoming the “Father of Railways.” Although modest in design compared to later locomotives such as Locomotion No. 1 (1825) or Rocket (1829), Blücher was a pioneering machine that proved the potential of steam power for hauling heavy loads on iron rails. Its construction marks a turning point in the story of modern transport.

This essay will explore the context, design, performance, and legacy of Blücher, highlighting why this locomotive deserves recognition as the foundation stone of Stephenson’s career and the wider railway revolution.

The Industrial Context of the Early 1800s

In the first two decades of the nineteenth century, Britain was experiencing rapid industrial growth. Coal was the lifeblood of this revolution, fuelling factories, steam engines, and domestic heating. Mines across Northumberland and Durham were producing vast quantities of coal, but transporting it efficiently to ports and markets was a major challenge.

Traditionally, coal wagons were pulled by horses along wooden or cast-iron wagonways, or transported via canals. These methods, though functional, were slow and costly. The invention of the steam engine in the eighteenth century had already revolutionised pumping in mines, and some engineers began to wonder whether steam power could also replace horses in hauling wagons.

The first experimental locomotives were built by Richard Trevithick in the early 1800s. His Penydarren locomotive of 1804 in South Wales is often cited as the first to haul a train along rails. However, these early attempts were hampered by technical limitations. Locomotives were heavy and often broke the fragile cast-iron rails; their designs were unreliable and uneconomical.

By the 1810s, the idea of locomotives had not yet been fully proven. It was into this climate that George Stephenson, a colliery engineer from Wylam in Northumberland, entered the field.

George Stephenson and His Opportunity

George Stephenson (1781–1848) was born into humble circumstances near Newcastle. His father was a colliery fireman, and George grew up around coal mining. Largely self-taught, Stephenson developed a keen mechanical aptitude, eventually becoming a colliery engineer. By 1812, he was working at Killingworth Colliery, where he was responsible for maintaining pumping engines and haulage systems.

Stephenson saw the inefficiencies of horse-drawn haulage firsthand. He became convinced that steam power could provide a better solution. Inspired by reports of Trevithick’s and other engineers’ experiments, Stephenson decided to build his own locomotive for Killingworth’s wagonway.

The colliery owners gave him permission, and in 1814, Stephenson constructed his first locomotive, naming it Blücher.

Naming the Locomotive: Why Blücher?

The locomotive was named after Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher (1742–1819), a Prussian field marshal famous for his role in the Napoleonic Wars. At the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, and later at Waterloo in 1815, Blücher’s forces played a decisive role in defeating Napoleon.

The choice of name reflected the patriotic fervour of the time: Britain and its allies were engaged in a titanic struggle with Napoleon, and naming the locomotive after a heroic general captured the spirit of victory and strength. It also perhaps suggested Stephenson’s own hopes that his machine would triumph in the “battle” to replace horse power.

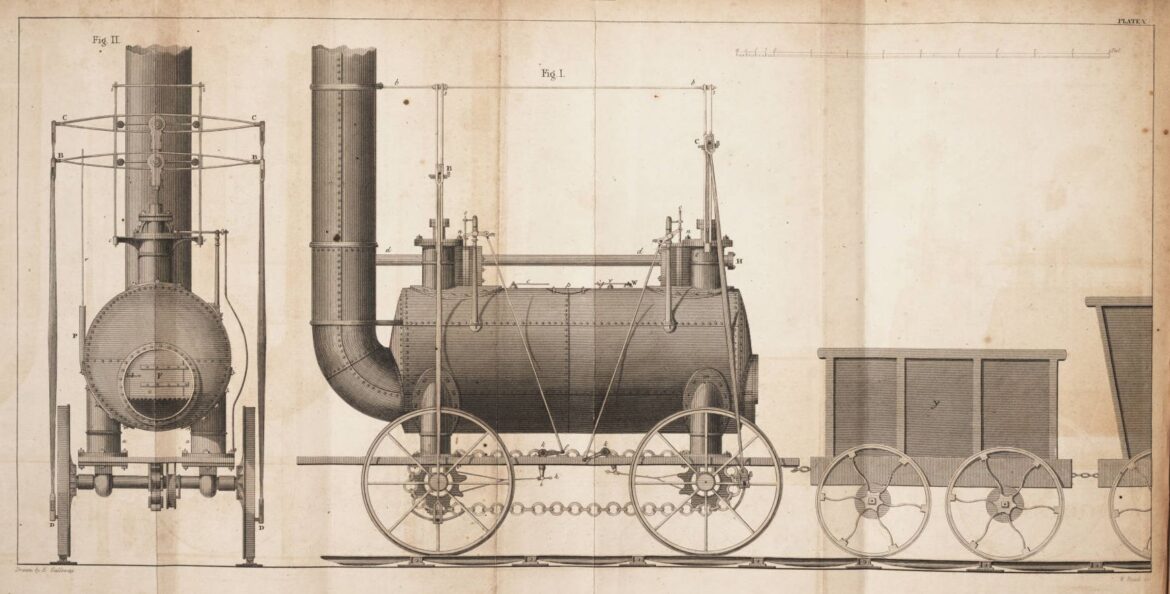

Design and Construction of Blücher

Blücher was built at the West Moor workshops of Killingworth Colliery. Stephenson used components from local blacksmiths and foundries, adapting existing engine technology for railway use.

The locomotive was an early 0-4-0 design (four coupled driving wheels, no leading or trailing wheels). Its key features included:

- Cylinders: Two vertical cylinders were mounted on the outside of the boiler.

- Drive Mechanism: Stephenson employed a system of cranks and rods to connect the pistons to the wheels.

- Boiler: A single-flue boiler generated the steam. It was relatively primitive compared to later multi-tubular boilers.

- Weight and Power: Blücher weighed around 6 tons and could haul about 30 tons of coal wagons at speeds of up to 4 miles per hour.

One of the most important innovations Stephenson introduced, though not fully perfected in Blücher, was the use of flanged wheels. Unlike Trevithick’s early locomotives, which relied on smooth wheels and sometimes gears engaging with racks, Stephenson’s locomotives used wheels with flanges that gripped the rails. This simple yet crucial idea ensured better traction and reduced slippage, making locomotives more practical for everyday use.

Performance and Early Problems

When Blücher was completed in 1814, it was tested on the Killingworth Wagonway. Reports indicate that it successfully pulled trains of coal wagons, proving that a steam locomotive could replace horse power. This was a major step forward.

However, the machine was far from perfect. Its vertical cylinders created a lurching motion that damaged the track, and its power output was limited. The cast-iron rails of the time were still relatively weak and prone to breaking under heavy loads. As a result, Blücher was not adopted as the sole mode of traction, and horses continued to be used alongside the locomotive.

Despite these shortcomings, the significance of Blücher lay in its demonstration that locomotives could work in practice. It provided Stephenson with invaluable experience, leading him to refine his designs over the following years.

Evolution After Blücher

Following the success of his first locomotive, Stephenson went on to build several improved engines for the Killingworth Wagonway. Between 1814 and 1816, he constructed at least 15 locomotives, each incorporating refinements such as horizontal cylinders, improved valve gear, and stronger boilers.

One of Stephenson’s most important innovations during this period was the steam blastpipe, which directed exhaust steam into the chimney, increasing draught through the fire and thereby improving boiler efficiency. This feature would become a standard element of nearly all subsequent steam locomotives.

By the early 1820s, Stephenson had established himself as a leading locomotive engineer. His appointment as chief engineer to the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1821 gave him the opportunity to design a railway specifically for steam locomotion. This culminated in the construction of Locomotion No. 1 in 1825, the engine that hauled the inaugural train of the world’s first public railway.

Thus, the path from Blücher led directly to the dawn of the modern railway age.

Legacy of Blücher

Although Blücher itself has not survived—it was eventually dismantled or scrapped—it occupies an honoured place in railway history. It was the first locomotive built by George Stephenson, the man who would go on to revolutionise transport not only in Britain but around the world.

Its importance lies not in its technical perfection but in its pioneering role. Like the Wright brothers’ early aircraft, it was a proof of concept. It showed what was possible, even if it was crude by later standards.

For the North East of England, Blücher represents the region’s central role in the birth of the railway. From Killingworth, Stephenson’s work spread to Darlington, Stockton, and beyond, transforming the economy and society. The global railway revolution, which enabled industrialisation, trade, and travel on an unprecedented scale, can trace part of its lineage back to this modest machine.

Cultural and Historical Recognition

Historians and railway enthusiasts have long recognised Blücher as a landmark. Models and reconstructions of the locomotive have been created to illustrate its appearance. It is often displayed in diagrams alongside Trevithick’s 1804 locomotive, Puffing Billy (1813), and later Stephenson designs to show the evolution of locomotive technology.

The name Blücher also reflects the era’s cultural atmosphere, when industrial achievements were often celebrated with martial or heroic associations. Just as bridges and ships were named after generals and victories, so too was Stephenson’s first locomotive tied to the contemporary spirit of resilience and triumph over adversity.

Conclusion

Blücher, George Stephenson’s first locomotive of 1814, may not have been the fastest, most efficient, or most elegant machine, but it was a true pioneer. Built in the industrial heartland of Northumberland, it successfully demonstrated that steam power could haul heavy loads along iron rails, laying the foundation for further development.

Its design flaws did not detract from its importance. Rather, they provided lessons that Stephenson used to improve subsequent locomotives. Without Blücher, there might never have been Locomotion No. 1 or Rocket, and without those, the railway revolution might have been delayed or taken a different course.

Today, even though the locomotive itself no longer exists, its legacy is remembered as the first step in George Stephenson’s extraordinary journey—a journey that reshaped the modern world. Blücher remains a symbol of invention, determination, and the transformative power of human ingenuity.