Introduction

The Human Genome Project (HGP) stands as one of the most ambitious and transformative scientific endeavors of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Its primary aim was deceptively simple: to determine the complete sequence of DNA that makes up the human genome and to identify and map all the genes within it. Yet behind this goal lay extraordinary scientific, technological, ethical, and societal challenges. Launched officially in 1990 and declared complete in 2003, the HGP fundamentally reshaped biology and medicine, ushering in the era of genomics and laying the foundation for modern precision medicine, biotechnology, and data-driven life sciences.

This essay explores the origins of the Human Genome Project, its objectives and methods, the technologies that made it possible, its key achievements, ethical and social implications, and its lasting impact on science and society.

Background and Origins

Before the Human Genome Project, genetics focused largely on individual genes and their associated traits or diseases. While researchers had successfully identified genes responsible for certain inherited conditions—such as cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia—this work was slow and labor-intensive. Scientists lacked a comprehensive reference map of the human genome, making it difficult to understand how genes interacted or how complex diseases arose from multiple genetic and environmental factors.

The idea of sequencing the entire human genome began to gain traction in the 1980s, driven by advances in molecular biology, computing, and automation. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), originally interested in understanding the genetic effects of radiation exposure, played a significant role in early discussions. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) soon became a central partner, and the project evolved into a large-scale international collaboration.

The Human Genome Project officially began in 1990, with funding primarily from the U.S. government, alongside major contributions from the United Kingdom, Japan, France, Germany, China, and other nations. From the outset, the project was notable not only for its scientific ambition but also for its unprecedented scale and level of international cooperation.

Objectives of the Human Genome Project

The HGP set out a number of clearly defined goals, which included:

- Determining the complete sequence of the approximately three billion base pairs that make up human DNA.

- Identifying and mapping all human genes, estimated at the time to number around 100,000 (later revised downward).

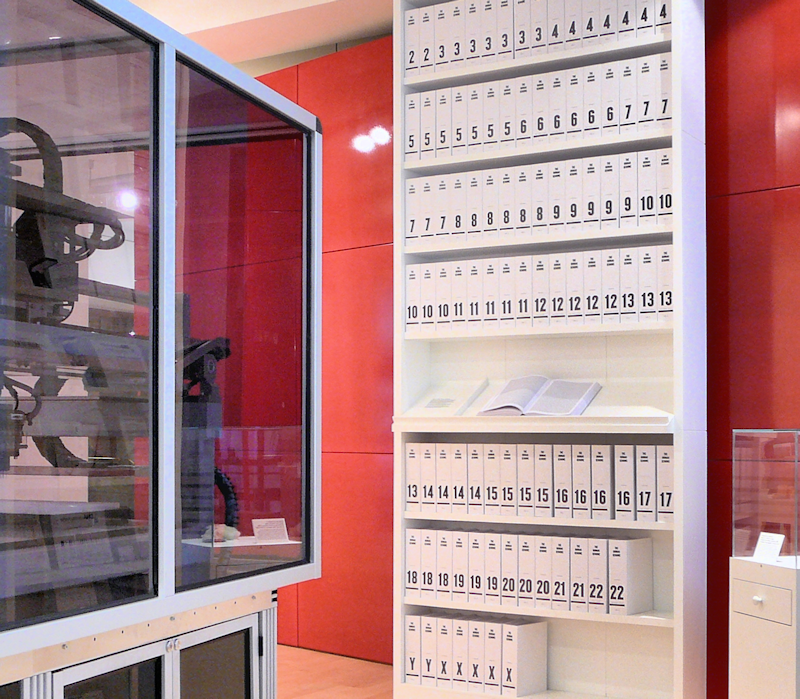

- Storing genomic data in publicly accessible databases.

- Developing faster, more accurate, and more cost-effective DNA sequencing technologies.

- Improving tools for data analysis, including computational methods and bioinformatics.

- Addressing the ethical, legal, and social implications (ELSI) of genomic research.

These objectives reflected an understanding that the project was not merely about sequencing DNA, but about building an entire scientific infrastructure capable of supporting future discoveries.

Methods and Technologies

DNA Sequencing

At the heart of the Human Genome Project was DNA sequencing—the process of determining the precise order of the four nucleotide bases (adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine) in DNA. Early in the project, sequencing relied primarily on the Sanger method, a technique developed in the 1970s. While reliable, it was slow and expensive, making large-scale genome sequencing a formidable challenge.

To overcome this, the HGP drove major innovations in automation and high-throughput sequencing. Robotic systems were developed to handle repetitive laboratory tasks, while fluorescent labeling and capillary electrophoresis significantly increased speed and accuracy. These advances laid the groundwork for later generations of sequencing technologies.

Mapping the Genome

Before sequencing could proceed efficiently, researchers needed maps of the genome. Two main types of maps were created:

- Genetic maps, which showed the relative positions of genes based on inheritance patterns.

- Physical maps, which identified the actual locations of DNA fragments on chromosomes.

By breaking the genome into manageable pieces and mapping them to known chromosomal locations, scientists could sequence fragments independently and then assemble them into a complete genome.

Bioinformatics and Computing

The sheer volume of data generated by the HGP was unprecedented in biology. Managing, storing, and analyzing this data required the development of new computational tools and databases. Bioinformatics emerged as a critical interdisciplinary field, combining biology, computer science, mathematics, and statistics.

Public databases such as GenBank allowed researchers worldwide to access genomic data freely, reinforcing the project’s commitment to open science and accelerating discovery across the life sciences.

Public vs. Private Efforts

In the late 1990s, the Human Genome Project faced unexpected competition from the private sector, most notably from Celera Genomics, led by Craig Venter. Celera proposed a faster approach using a technique known as whole-genome shotgun sequencing, combined with powerful computational assembly methods.

This competition intensified the pace of discovery and sparked debates over data ownership and access. While the publicly funded HGP emphasized free and open data sharing, private companies sought to patent certain genetic sequences. Ultimately, both efforts contributed to the draft human genome announced in 2000, followed by the publication of more refined sequences in 2001.

The rivalry, though controversial, played a role in accelerating technological innovation and reducing sequencing costs.

Key Findings and Achievements

One of the most surprising outcomes of the Human Genome Project was the realization that humans possess far fewer genes than originally expected—approximately 20,000 to 25,000, rather than the predicted 100,000. This finding challenged simplistic notions of genetic determinism and highlighted the complexity of gene regulation, alternative splicing, and protein interactions.

The HGP also revealed that:

- Less than 2% of the human genome codes directly for proteins.

- Large portions of the genome consist of regulatory elements, repetitive sequences, and non-coding RNA.

- Humans share a significant proportion of their DNA with other organisms, underscoring the evolutionary continuity of life.

Beyond these insights, the project provided a foundational reference genome that continues to guide research into disease mechanisms, human evolution, and biological diversity.

Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (ELSI)

Recognizing the profound societal implications of genomic knowledge, the Human Genome Project was the first large scientific initiative to formally allocate a portion of its budget—approximately 3–5%—to the study of ethical, legal, and social issues.

Key concerns included:

- Genetic privacy: Who should have access to an individual’s genetic information?

- Discrimination: The potential misuse of genetic data by employers or insurers.

- Informed consent: Ensuring individuals understand the implications of genetic testing.

- Psychological impact: How knowledge of genetic risk might affect individuals and families.

These discussions contributed to the development of policies and legislation, such as genetic non-discrimination laws in several countries. The ELSI program also set a precedent for integrating ethics into large-scale scientific research.

Impact on Medicine and Healthcare

Perhaps the most significant long-term impact of the Human Genome Project has been on medicine. By providing a detailed map of human genetic variation, the HGP paved the way for:

- Precision medicine: Tailoring medical treatment to an individual’s genetic profile.

- Pharmacogenomics: Understanding how genetic differences influence drug response.

- Improved diagnostics: Identifying genetic mutations associated with inherited and complex diseases.

- Gene-based therapies: Developing treatments that target underlying genetic causes.

While the full promise of genomic medicine is still being realized, the HGP transformed the way diseases are studied and treated, shifting focus from symptoms to molecular mechanisms.

Broader Scientific and Economic Impact

Beyond healthcare, the Human Genome Project had wide-ranging effects on science and the global economy. It stimulated growth in biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries, created new career paths in genomics and data science, and contributed to the rapid decline in DNA sequencing costs—from billions of dollars per genome to a few hundred today.

The project also influenced research culture, promoting large-scale collaboration, data sharing, and interdisciplinary approaches. These principles have since been adopted in other fields, from neuroscience to climate science.

Limitations and Continuing Work

Although the HGP was declared complete in 2003, this did not mean the human genome was fully understood. Early reference genomes contained gaps and were not fully representative of global genetic diversity. Subsequent initiatives, such as the HapMap Project, the 1000 Genomes Project, and more recent pan-genome efforts, have sought to address these limitations.

Understanding gene regulation, epigenetics, and gene–environment interactions remains an ongoing challenge, underscoring that the HGP was a beginning rather than an endpoint.

Conclusion

The Human Genome Project was a landmark achievement that transformed biology into a data-intensive, genome-centered science. Through international collaboration, technological innovation, and a commitment to ethical reflection, it delivered a comprehensive blueprint of human DNA and reshaped our understanding of life itself.

Its legacy is evident in modern medicine, biotechnology, and scientific research, influencing how we diagnose disease, develop treatments, and explore human origins. While many challenges remain in fully interpreting and applying genomic information, the Human Genome Project stands as a testament to what can be achieved when scientific ambition is matched by cooperation, foresight, and responsibility.