When The Killing Fields premiered in 1984, it struck audiences with the force of both a historical revelation and a deeply personal human tragedy. Directed by Roland Joffé and written by Bruce Robinson, the film is a haunting depiction of friendship, survival, and moral duty set against one of the most horrifying genocides of the 20th century—the Cambodian Killing Fields. Based on the true story of New York Times journalist Sydney Schanberg and his Cambodian colleague and friend Dith Pran, the film takes viewers from the chaos of war reporting to the unimaginable horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime.

More than a war movie, The Killing Fields is a meditation on conscience, loyalty, and the power—and limits—of journalism in the face of atrocity. It explores the question of what it means to bear witness: to see horror unfold, to report it truthfully, and to live with the knowledge that words and images may never be enough to stop it.

The Setting: Cambodia in Turmoil

The story begins in 1973, as the Vietnam War spills over into neighboring Cambodia. The United States is secretly bombing parts of the country in an effort to disrupt North Vietnamese supply routes, but the bombing has destabilized Cambodia’s fragile government and fueled the rise of the Khmer Rouge, a radical communist movement led by Pol Pot.

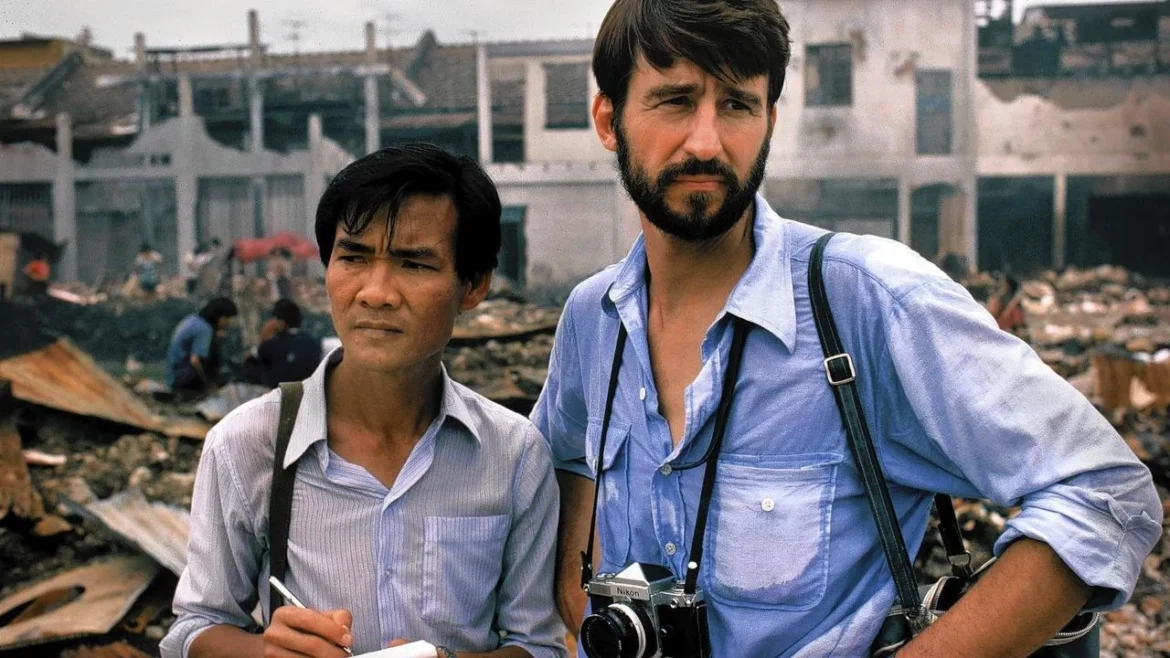

Into this chaos come the foreign correspondents—reporters and photographers seeking to document the unfolding crisis. Among them is Sydney Schanberg (played by Sam Waterston), a driven and ambitious journalist for The New York Times. His local translator and guide, Dith Pran (played by Haing S. Ngor), is invaluable—smart, resourceful, and courageous. Together, they form a partnership that transcends professional boundaries, evolving into a deep friendship built on trust and mutual respect.

The first half of the film focuses on their work as war correspondents: dodging bullets, navigating military checkpoints, and racing against deadlines to get the truth out to the world. Joffé captures the energy and danger of journalism in a war zone with gripping realism. The streets are filled with fear and uncertainty, and the journalists must balance their duty to report with their own instinct for survival.

But as the Khmer Rouge draws closer to Phnom Penh, the tone of the film shifts from adrenaline-fueled urgency to suffocating dread. When the regime finally seizes power in 1975, the journalists are evacuated—but Dith Pran, as a Cambodian, is forced to stay behind. What follows is one of the most harrowing depictions of human suffering ever committed to film.

Friendship and Guilt

The relationship between Schanberg and Pran lies at the heart of The Killing Fields. Their bond represents not only friendship but also the uneasy alliance between Western journalists and their local collaborators—men and women who risked everything to help the press tell the world what was happening.

Schanberg, portrayed with emotional restraint by Sam Waterston, is a man driven by ideals yet haunted by guilt. He believes in the power of journalism to reveal truth and hold the powerful accountable. But when Pran is trapped in Cambodia, Schanberg’s idealism collapses into self-reproach. He cannot forgive himself for escaping while his friend remains behind, suffering because of their shared work.

The scenes of Schanberg’s life back in New York are suffused with emptiness. The bustling newsroom, the awards ceremonies, and the polite conversations feel hollow in contrast to the agony of not knowing whether Pran is alive. Waterston’s performance captures this torment perfectly—his pride as a journalist warring with his shame as a man who left his friend behind.

Pran’s story, meanwhile, unfolds in parallel—and it is here that The Killing Fields becomes something far greater than a journalistic drama.

Haing S. Ngor: A Performance Beyond Acting

Haing S. Ngor’s portrayal of Dith Pran is extraordinary not only for its emotional depth but also for the fact that Ngor himself was a survivor of the Khmer Rouge. A doctor before the war, he had lived through the terror of Pol Pot’s regime, enduring imprisonment, torture, and the loss of his wife before escaping to Thailand. He had never acted before, yet his performance is one of the most authentic and moving in cinema history.

Through Ngor’s eyes, the audience experiences the horror of the “Year Zero” that Pol Pot declared upon taking power—the systematic dismantling of Cambodia’s society. The Khmer Rouge emptied the cities, abolishing money, education, religion, and family ties in a fanatical attempt to create a classless agrarian utopia. In reality, it became a nightmare of starvation, executions, and forced labor.

Pran, stripped of his identity and forced to conceal his past as a journalist, becomes a prisoner in his own country. The film shows his transformation from a proud professional to a silent survivor, enduring unspeakable suffering with quiet resilience. He witnesses the killing fields—vast burial sites where thousands are executed and buried in mass graves.

Joffé does not sensationalize this horror; instead, he presents it with stark, unflinching realism. The camera lingers on Pran’s face as he watches others die, his silence conveying more than any dialogue could. The sound of insects and the distant cries of the dying create an atmosphere of unbearable tension.

Ngor’s performance won him the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, making him the first Asian non-professional actor to win an Oscar. His acceptance of the award carried profound weight—he had not only portrayed a survivor but lived as one.

The Power and Limits of Journalism

At its core, The Killing Fields is also a film about journalism—its nobility, its arrogance, and its moral complexity. Schanberg and Pran risked their lives to bring the truth to light, but the film raises an uncomfortable question: what good does the truth do when the world refuses to act?

During one tense exchange early in the film, Schanberg argues with a military officer about the bombing of Cambodia. “We report the facts,” he says. But facts alone, as the film suggests, are powerless without empathy. The journalists expose atrocities, yet governments continue their destructive policies, and the killing goes on.

When Schanberg later receives a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting, the moment feels almost obscene. The applause and admiration of his peers only amplify his guilt. His words may have changed headlines, but they could not save his friend—or the millions who perished.

The film thus becomes an indictment not only of political leaders but also of a world numbed by information. It reminds us that bearing witness is not enough; compassion and action must follow.

The Cinematic Craft

Visually, The Killing Fields is stunning. Cinematographer Chris Menges captures both the lush beauty of Cambodia’s landscape and the brutality of its destruction. The golden light of the rice fields contrasts sharply with the darkness of the labor camps, symbolizing the loss of innocence and the descent into barbarism.

The sound design is equally powerful—especially the haunting use of silence in the second half of the film. When the noise of war fades, it’s replaced by an eerie stillness, broken only by the sounds of the jungle and human suffering.

And then there is Mike Oldfield’s score—a blend of haunting melodies and electronic rhythms that perfectly underscores the film’s emotional journey. His theme for Dith Pran’s escape sequence, with its pulsating intensity, elevates the scene from mere suspense to transcendence. It is as if the music itself is praying for deliverance.

Themes of Humanity and Survival

Ultimately, The Killing Fields is a story about endurance and the will to live. Dith Pran’s survival is not heroic in the traditional sense—it is an act of quiet defiance against the machinery of death. His courage lies not in grand gestures but in persistence: in continuing to walk, to breathe, to remember.

The film also explores the resilience of friendship. Though separated by continents and ideology, Schanberg and Pran remain connected through their shared humanity. When they are finally reunited in the film’s climax—a scene wordlessly underscored by John Lennon’s “Imagine”—the emotion is overwhelming. It’s not triumph we feel, but relief, sorrow, and the weight of everything lost.

The reunion is brief and understated, yet it carries the full gravity of the film’s moral vision. In that embrace, there is forgiveness—not only between two friends, but between witness and survivor, between guilt and grace.

Legacy and Reflection

Four decades after its release, The Killing Fields remains one of the most powerful war films ever made—not because of its violence, but because of its humanity. It transcends the genre of war cinema to become something much deeper: a meditation on moral responsibility, friendship, and the cost of truth.

It also serves as a historical document, preserving the memory of a genocide that the world was too slow to acknowledge. Between 1975 and 1979, nearly two million Cambodians—about a quarter of the population—died under the Khmer Rouge. The Killing Fields ensures that their suffering is not forgotten.

In an era of instant news and desensitization to tragedy, the film’s message is more relevant than ever. It reminds us that behind every headline are real human lives—and that telling their stories is both a privilege and a burden.

Conclusion: Bearing Witness

The Killing Fields is not an easy film to watch, nor should it be. It confronts the viewer with the darkest aspects of humanity while offering glimpses of compassion and redemption. It challenges us to look, to remember, and to care.

In the end, the film’s greatest achievement is that it humanizes history. Through the friendship of Sydney Schanberg and Dith Pran, it transforms political tragedy into personal truth. And in doing so, it reaffirms the power of storytelling—not to erase suffering, but to ensure that those who suffered are never silenced.

As Dith Pran walks out of the Cambodian jungle into freedom, the film closes not with celebration but with a quiet plea for understanding. The killing fields are not just a place—they are a warning. And the duty to remember them belongs to us all.