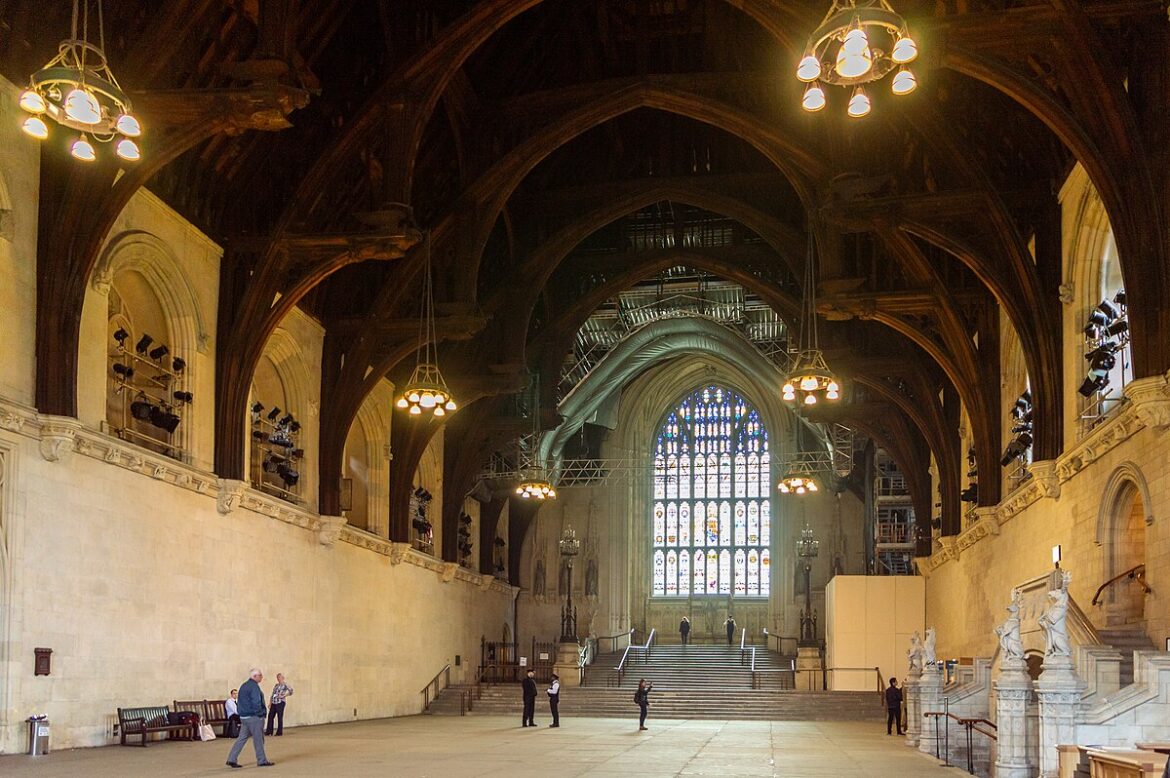

Westminster Hall, standing proudly at the heart of the Palace of Westminster in London, is one of the most remarkable and enduring architectural achievements of medieval England. As the oldest surviving part of the complex, its history spans over 900 years, making it not only an architectural marvel but also a place of immense political, judicial, and ceremonial importance. From its foundation in the late 11th century to its continuing role in state occasions today, Westminster Hall embodies the evolving story of the English nation.

Origins and Early Construction

Westminster Hall was built in 1097 under the orders of King William II, commonly known as William Rufus, the son of William the Conqueror. His intention was to create a hall that would eclipse any similar structure in Europe, a statement of royal authority and prestige. At the time of its completion, it was the largest hall in England, measuring an impressive 73 by 20 meters (240 by 67 feet). Its sheer size astonished contemporaries and underscored the power of the Norman monarchy.

The hall’s primary function in its early years was as a royal audience chamber, where the king could hold court and entertain his nobles. Banquets, feasts, and important assemblies were hosted within its walls. It formed the ceremonial and administrative heart of the Norman royal palace at Westminster, which would later evolve into the seat of Parliament.

Architectural Significance

The original hall constructed by William Rufus featured thick stone walls, massive windows, and a simple roof supported by two rows of pillars running down its length. While impressive in size, this early roof design divided the space and lacked the grandeur that later defined the building.

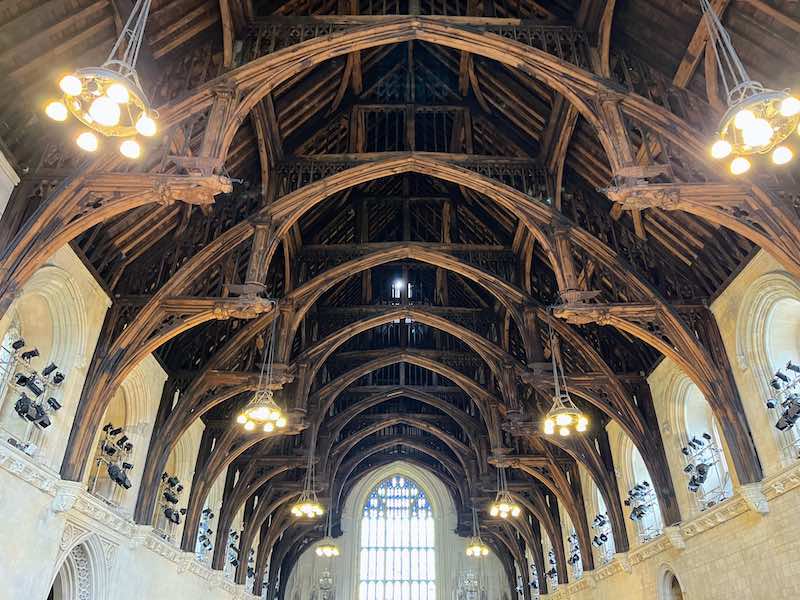

A major transformation occurred under King Richard II in the late 14th century. In 1393, Richard ordered the reconstruction of the roof to replace the earlier Norman pillars with a spectacular open timber roof. Designed by Hugh Herland, the royal carpenter, this new hammer-beam roof remains one of the finest achievements of medieval carpentry in the world.

The hammer-beam structure allowed the roof to span the full width of the hall without the need for central supports. The effect was both practical and symbolic: it created an unobstructed interior space that could accommodate thousands of people, while also demonstrating the wealth and technical sophistication of the English crown. The wooden beams, richly carved with angels and other motifs, added a spiritual and decorative quality to the hall, reinforcing the link between monarchy and divine sanction.

This roof remains one of the defining features of Westminster Hall, admired both for its engineering ingenuity and its aesthetic grandeur.

Judicial Functions

From the medieval period until the 19th century, Westminster Hall served as the centre of the English judicial system. Several of the most important courts in the kingdom convened within its walls, including the Court of King’s Bench, the Court of Chancery, and the Court of Common Pleas.

Here, great legal cases were argued and decisions handed down that shaped the course of English common law. The hall was a place where monarchs and subjects alike might find themselves facing judgment. The legal function of Westminster Hall gave it an aura of solemnity, as justice was dispensed in view of the public, reinforcing both the majesty and accountability of the crown.

Perhaps the most dramatic judicial episodes in Westminster Hall were the great state trials. The hall witnessed the trial of Sir Thomas More in 1535, who refused to acknowledge Henry VIII as the supreme head of the Church of England. More’s eloquence and martyrdom elevated the trial into a moment of enduring significance.

The hall was also the setting for the trial of Guy Fawkes and his fellow conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, where they were convicted of attempting to blow up the Houses of Parliament. In the 17th century, it hosted one of the most extraordinary trials in English history: that of King Charles I in 1649. Charged with treason against his own people, Charles was tried in Westminster Hall before being executed outside the Banqueting House at Whitehall. This trial marked a profound constitutional turning point, underscoring the notion that a monarch could be held accountable by Parliament and the people.

Ceremonial Role

While it functioned as a court of law, Westminster Hall was also deeply tied to royal and state ceremony. It hosted magnificent coronation banquets for English monarchs from the Middle Ages until the 19th century. These events were lavish affairs, involving pageantry, music, and ritual that asserted the legitimacy of the monarch’s rule.

The hall was also used for lying-in-state ceremonies, a tradition that continues today. The coffins of monarchs, consorts, and significant figures are placed in Westminster Hall to allow the public to pay their respects. Notable recent examples include Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in 2002 and Queen Elizabeth II in 2022. In such moments, Westminster Hall serves as a bridge between the monarchy and the people, a space where national grief and unity can be expressed.

Additionally, Westminster Hall has been the stage for historic addresses by visiting dignitaries. Figures such as Nelson Mandela, Pope Benedict XVI, and Barack Obama have all spoken there, underscoring its continuing role as a symbol of democratic values and international diplomacy.

The Hall and Parliament

As Parliament grew in importance from the 13th century onward, Westminster Hall became increasingly associated with the governance of the realm. It was adjacent to the chambers where the House of Commons and the House of Lords met, and the great hall often acted as an antechamber for political life.

The proximity of law courts, parliamentary sessions, and royal ceremonies within the palace complex meant that Westminster Hall was a focal point of English political culture. It symbolised the interconnectedness of monarchy, law, and legislature. Even after the law courts moved out in the 19th century to the Royal Courts of Justice on the Strand, the hall retained its symbolic association with parliamentary sovereignty.

Survival Through Fire and War

The Palace of Westminster has suffered catastrophic fires over the centuries, most notably in 1512 and 1834. Both times, much of the complex was destroyed or damaged. Remarkably, Westminster Hall survived these disasters almost unscathed, a testament to both its robust construction and its importance in the national consciousness.

During the Blitz of World War II, the hall again narrowly escaped destruction. Bombs fell on the surrounding Palace of Westminster, destroying the House of Commons chamber in 1941, but Westminster Hall was spared. Its preservation during these moments of crisis reinforced its role as a guardian of continuity and tradition amidst upheaval.

Restoration and Preservation

Over the centuries, Westminster Hall has required careful restoration and conservation to maintain its structural integrity. The hammer-beam roof in particular has demanded attention, given its age and exposure to environmental factors. Victorian restorers undertook significant work to preserve the hall, and modern conservation techniques continue to safeguard its timber and stonework.

Efforts to maintain Westminster Hall are not simply about architecture—they are about preserving a living monument to the nation’s identity. The hall remains accessible to the public, both as part of the parliamentary estate and as a heritage site, allowing visitors to walk in the footsteps of kings, queens, judges, and reformers.

Symbolism and Legacy

What makes Westminster Hall so significant is not just its architectural magnificence, but its layered history. It has been at once a royal palace, a court of law, a ceremonial stage, and a parliamentary space. Few buildings encapsulate so vividly the story of England’s transition from absolute monarchy to constitutional democracy.

Its hammer-beam roof speaks of medieval ambition and craftsmanship. Its trials and legal proceedings speak of justice and accountability. Its ceremonial functions link it to monarchy and nation. And its survival through fire and war speaks of resilience.

Westminster Hall endures as a place where the past and present converge. When dignitaries speak there, they do so under the same roof where kings were judged, martyrs condemned, and constitutions shaped. It is both a physical space and a symbolic heart of British political culture.

Conclusion

Westminster Hall is more than a medieval relic: it is a living monument to English history and identity. Constructed by William Rufus to impress and dominate, transformed by Richard II into a masterpiece of carpentry, and preserved through centuries of turmoil, it remains a site where the nation gathers in times of celebration, crisis, and reflection.

Its role in the administration of law and justice, in the coronation and funeral of monarchs, and in the speeches of world leaders ensures that Westminster Hall remains a space where history is not only remembered but continually made. For over nine centuries, it has stood as a witness to the evolving story of the British state—and it continues to inspire awe in all who walk beneath its great roof.