Introduction

The Highland Boundary Fault (HBF) is one of the most significant geological features in Scotland, marking a major division between the Highlands and the Lowlands. Stretching diagonally across the country from Arran in the southwest to Stonehaven in the northeast, this fault line represents a fundamental boundary between two vastly different geological terrains. The Highlands, dominated by ancient, hard metamorphic and igneous rocks, contrast sharply with the softer sedimentary rocks of the Lowlands. The fault line not only shaped Scotland’s natural landscape but also influenced human settlement, agriculture, and historical development.

Geological Formation and Structure

The Highland Boundary Fault is a product of tectonic forces dating back hundreds of millions of years. During the late Precambrian and early Paleozoic eras (over 500 million years ago), Scotland was part of a much larger landmass. The fault was formed during the Caledonian orogeny, a mountain-building event caused by the collision of ancient continents Laurentia, Baltica, and Avalonia. This collision compressed and deformed the crust, uplifting the rugged Highlands while leaving the Lowlands relatively undisturbed.

The fault is a complex structure comprising several fracture zones, with evidence of both thrust and strike-slip faulting. Over time, differential erosion of the rock types on either side of the fault has accentuated the divide, with the resistant metamorphic and igneous rocks of the Highlands forming steep, mountainous terrain and the softer, more easily eroded sedimentary rocks of the Lowlands creating gentler landscapes.

Geographic Extent

The Highland Boundary Fault runs in a southwest-northeast direction, cutting across Scotland and defining the transition between two contrasting geological regions. Key locations along the fault include:

- Arran – The island of Arran provides one of the most striking examples of the fault, with a dramatic contrast between the rugged northern Highlands and the softer Lowland terrain to the south.

- Loch Lomond – The boundary runs through this iconic loch, with the steep hills of the Highlands rising to the north and the gentler slopes of the Lowlands extending southwards.

- Aberfoyle – This town sits directly on the fault line and has long been a site of geological study, providing clear evidence of rock formations associated with the fault.

- Dunkeld – The fault passes through Dunkeld and Birnam, where the landscape transitions sharply from the mountainous north to the rolling farmland of the south.

- Stonehaven – At the easternmost extent, the fault reaches the North Sea near Stonehaven, where it is visible in the coastal cliffs.

Impact on Landscape and Environment

The Highland Boundary Fault has played a crucial role in shaping Scotland’s topography. The stark contrast between the Highlands and Lowlands is largely attributable to the fault and the different types of rock on either side. The Highlands, composed mainly of hard metamorphic rocks such as schist and gneiss, have been more resistant to erosion, resulting in rugged mountains, deep glens, and dramatic lochs. In contrast, the Lowlands consist of softer sedimentary rocks like sandstone and limestone, which have been more easily eroded over time, creating rolling hills and fertile valleys.

The fault line has also influenced the course of rivers and lochs. Many of Scotland’s major lochs, including Loch Lomond, follow the fault line, forming elongated basins that were further shaped by glacial activity during the Ice Ages. The movement of ice sheets carved out deep valleys along the fault, contributing to the dramatic scenery seen today.

Influence on Human Settlement and Development

The geological divide created by the Highland Boundary Fault has had significant implications for human history and settlement patterns in Scotland. The fertile, low-lying lands to the south of the fault were more suitable for agriculture, leading to the development of early farming communities and later towns and cities such as Glasgow, Stirling, and Perth. In contrast, the rugged terrain of the Highlands made large-scale farming difficult, leading to a reliance on subsistence agriculture, livestock herding, and fishing.

The fault line also played a role in Scotland’s historical conflicts. The natural boundary created by the Highlands and Lowlands contributed to cultural and political divisions. The Highland clans, with their distinct Gaelic culture, were often at odds with the more Anglicized Lowland populations. This division played a role in events such as the Wars of Scottish Independence, the Jacobite uprisings, and the eventual decline of the Highland way of life following the Highland Clearances in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Economic and Industrial Impact

The presence of the Highland Boundary Fault has had an impact on Scotland’s economic history. The differing rock types on either side of the fault have led to various natural resources being exploited. The Highlands have long been known for their deposits of valuable minerals, including gold, lead, and copper, though mining operations have remained relatively small-scale. The Lowlands, in contrast, have abundant coal and limestone deposits, which played a crucial role in Scotland’s industrial revolution.

Glasgow and other Lowland cities benefited from the proximity of coal and iron ore deposits, fueling the rise of heavy industries such as shipbuilding, steel production, and engineering. Meanwhile, the Highlands remained largely rural, with industries focused on agriculture, forestry, and whisky production.

Seismic Activity and Modern Geological Studies

Though the Highland Boundary Fault is no longer tectonically active in the same way it was during its formation, it still experiences minor seismic activity. Scotland is not known for major earthquakes, but small tremors occasionally occur along the fault line, typically measuring below magnitude 4.0 on the Richter scale. These quakes are not usually strong enough to cause damage but serve as a reminder of the region’s geological history.

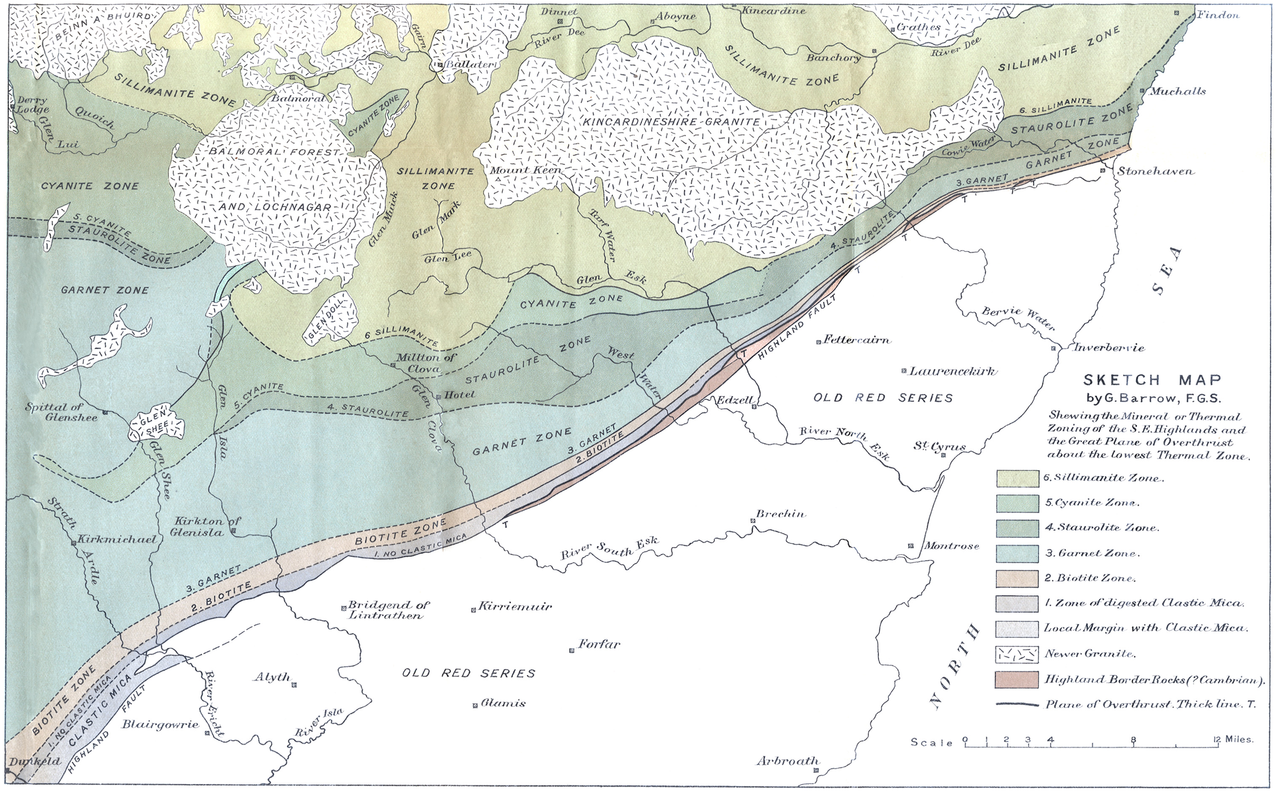

Modern geologists continue to study the Highland Boundary Fault to understand Scotland’s geological past. Advances in technology, such as satellite imaging and seismic monitoring, have allowed for more detailed mapping of the fault’s structure and movement. These studies help scientists better understand not only Scotland’s geological evolution but also broader tectonic processes that have shaped the British Isles.

Tourism and Educational Significance

The Highland Boundary Fault is an important feature for geotourism and education. Visitors to Scotland can explore various locations along the fault to witness the dramatic changes in landscape firsthand. Places like Loch Lomond and The Trossachs National Park, the Isle of Arran, and the Stonehaven coastline offer excellent opportunities for geology enthusiasts to observe rock formations and learn about the fault’s impact on the region.

Educational institutions and museums, such as the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and the Loch Lomond and The Trossachs visitor centers, provide resources for those interested in Scotland’s geological history. Additionally, guided geological tours in areas like Aberfoyle offer in-depth insights into the fault’s formation and significance.

Conclusion

The Highland Boundary Fault is much more than just a geological feature—it is a defining element of Scotland’s natural and cultural identity. From its role in shaping the rugged landscapes of the Highlands and the fertile plains of the Lowlands to its influence on historical conflicts and economic development, the fault line has left an indelible mark on Scotland’s past and present. As scientific research continues, our understanding of this remarkable geological boundary will only deepen, offering new insights into the dynamic forces that have shaped Scotland for millions of years.