Zen Buddhism is a school of Mahāyāna Buddhism that emphasizes direct, experiential realization of one’s true nature through meditation, intuition, and mindfulness in everyday life. Rooted in the Chinese tradition of Chan Buddhism, which in turn was influenced by Indian Mahāyāna thought and Daoist philosophy, Zen blossomed in Japan and later spread to the West, where it has become synonymous with a minimalist, contemplative approach to spirituality.

What sets Zen apart from other forms of Buddhism is its reliance on personal insight over doctrinal study, its stark and disciplined aesthetic, and its rigorous yet poetic methods for awakening. Zen teaches that enlightenment is not a distant goal, but a truth that can be realized in the present moment—right here, right now.

Historical Origins

Zen originated in China as Chan Buddhism during the 6th century CE, a fusion of Indian Mahāyāna teachings—especially those emphasizing meditation—and Chinese Daoist sensibilities. The legendary figure often credited as the first patriarch of Chan is Bodhidharma, an Indian monk who is said to have arrived in China and taught a form of Buddhism focused on seated meditation (zazen) and insight into the nature of mind.

The term “Chan” (禪) comes from the Sanskrit word “dhyāna”, meaning meditation. When Chan Buddhism spread to Japan around the 12th century, it became known as Zen, retaining its core emphasis on meditation while adapting to Japanese cultural forms.

Zen flourished in Japan under the Rinzai and Sōtō schools. The Rinzai school emphasized koan practice—short, paradoxical sayings or questions meant to provoke insight—while Sōtō emphasized shikantaza, or “just sitting,” a form of silent, objectless meditation.

Core Tenets of Zen Buddhism

Zen Buddhism is rooted in Mahāyāna principles, but it expresses them through a stripped-down, experiential lens. It avoids metaphysical speculation and instead turns attention to what is directly observable and lived.

1. Direct Experience Over Scripture

One of the foundational sayings of Zen is:

“A special transmission outside the scriptures,

Not founded upon words and letters,

By pointing directly to one’s mind,

It lets one see into one’s true nature and attain Buddhahood.”

Zen does not reject scriptures entirely but sees them as secondary to direct realization. Enlightenment cannot be grasped intellectually; it must be lived.

2. The Nature of Mind

Zen teaches that Buddha-nature is inherent in all beings. Enlightenment (satori) is not something attained from outside but realized by turning inward and seeing things as they truly are—free from distortion, grasping, and conceptual overlays.

3. Non-Dualism

Like other Mahāyāna schools, Zen emphasizes non-duality. Distinctions such as subject and object, self and other, or sacred and profane are seen as mental constructs. In Zen, the absolute and relative coexist in every moment.

4. Everyday Mind is the Way

Zen finds truth in everyday experience. Enlightenment is not confined to monastic life or mystical states but is present in chopping wood, carrying water, making tea, or sweeping the floor. Ordinary activities become extraordinary when performed with full attention and presence.

Zen Practice

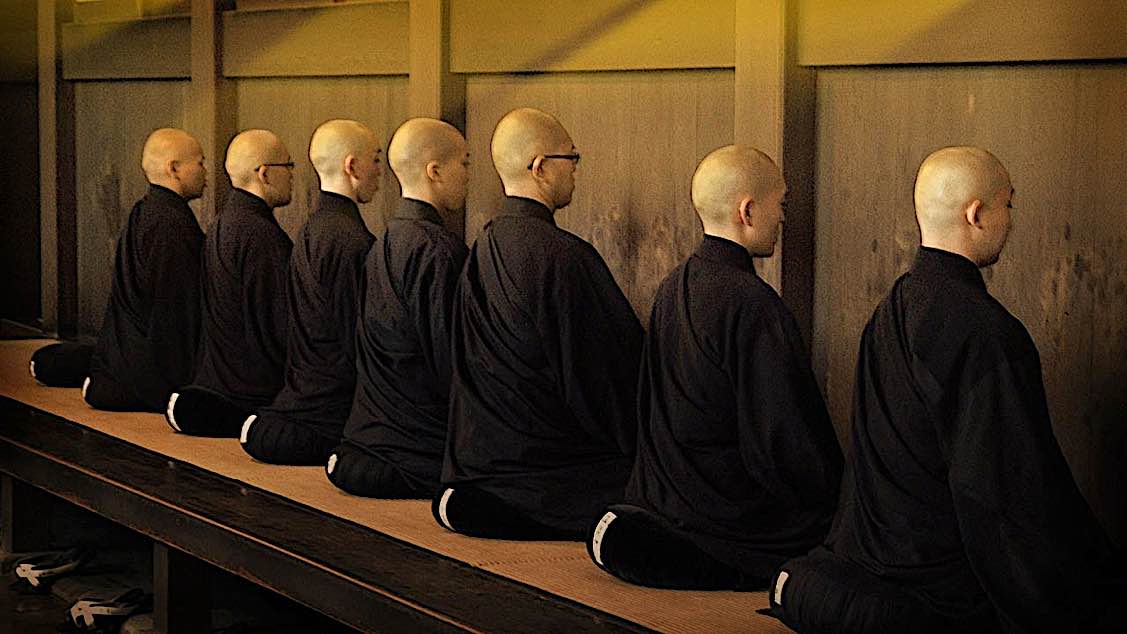

Zazen (Seated Meditation)

The cornerstone of Zen is zazen, or seated meditation. In zazen, the practitioner sits in a stable posture, often the full or half lotus, with eyes open and awareness resting on the breath, posture, or simply the act of being.

Two main approaches to zazen exist:

- Shikantaza (Just Sitting) – Practiced in Sōtō Zen, this involves sitting with no specific object of meditation, allowing thoughts to rise and fall without attachment.

- Koan Practice – Used in Rinzai Zen, this involves meditating on a koan—a paradoxical statement or question that defies logical thinking, such as: “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

The goal is not to arrive at an answer but to break through conceptual thinking and experience a moment of awakening or kenshō (“seeing into one’s nature”).

Mindfulness in Action

Zen is not confined to the meditation cushion. Walking, eating, cleaning, and working are all opportunities to practice mindfulness. Samu, or work practice, is an essential part of Zen training, reflecting the belief that awakening can occur in any activity when done with full awareness.

Teacher-Student Relationship

Zen relies on the transmission of insight from teacher to student, often through dialogue, example, and shared silence rather than formal instruction. The teacher may use unconventional methods—shouting, silence, sudden blows—to jolt the student out of habitual thinking.

Koans: The Art of Paradox

Koans are a unique and defining feature of Zen practice. These short, enigmatic dialogues or questions are designed to disrupt logical reasoning and provoke a sudden shift in perception.

Examples include:

- Joshu’s Mu: A monk asked, “Does a dog have Buddha-nature?” Joshu answered, “Mu” (meaning “no” or “not”).

- What was your original face before your parents were born?

These challenges cannot be solved rationally. Instead, they lead the student to exhaust conceptual thought and leap into a direct, non-conceptual realization of truth.

Zen Aesthetics and Culture

Zen has had a profound influence on Japanese culture and the arts, cultivating a refined, minimalist aesthetic rooted in simplicity, impermanence, and naturalness.

1. Wabi-Sabi

Zen aesthetics embrace wabi-sabi, the beauty of imperfection, asymmetry, and transience. A cracked tea bowl or weathered stone may be valued more than something pristine.

2. The Tea Ceremony (Chanoyu)

The Japanese tea ceremony reflects Zen principles: mindfulness, simplicity, attention to detail, and harmony with nature. Every movement is performed with grace and presence.

3. Zen Arts

Zen inspired various forms of artistic expression, including:

- Sumi-e (ink painting)

- Karesansui (rock gardens)

- Haiku (minimalist poetry capturing fleeting moments)

- Calligraphy, which expresses the artist’s mind in a single stroke

These arts are not merely aesthetic but spiritual disciplines—forms of meditation in motion.

Zen in the Modern World

Zen Buddhism found its way to the West in the 20th century through writers, scholars, and teachers such as D.T. Suzuki, Shunryu Suzuki, Philip Kapleau, and Thich Nhat Hanh. It has attracted artists, philosophers, psychologists, and seekers looking for a grounded, non-dogmatic approach to spirituality.

Today, Zen centers exist across North America, Europe, and Australia, often emphasizing lay practice and integrating with modern life.

Zen has also deeply influenced:

- Psychology – Especially in areas like mindfulness-based therapy.

- Philosophy – Zen’s rejection of dualism and language parallels certain strands of existentialism and post-structuralism.

- Business and Leadership – Zen’s focus on presence and clarity is seen in some approaches to mindful leadership and design thinking.

Challenges and Critiques

While Zen offers profound insights, it is not without challenges:

- Cultural Adaptation: Zen’s emphasis on form and ritual can seem rigid or obscure to Western practitioners.

- Power Dynamics: Like many spiritual traditions, some Zen communities have faced issues of authority abuse and misconduct.

- Anti-Intellectualism: Zen’s distrust of scholarly learning, while valuable in some respects, can also discourage critical inquiry.

Nonetheless, when practiced with integrity and sincerity, Zen remains a powerful tool for transformation.

Conclusion

Zen Buddhism offers a radical, beautiful, and uncompromising approach to spiritual life. It strips away metaphysical speculation, theological complexity, and even words themselves to ask a simple yet profound question: “Who are you, really, right now?”

In a world that often pulls us away from the present moment, Zen calls us back to simplicity, silence, and the wonder of being alive. Whether one seeks formal enlightenment or simply a clearer, calmer mind, Zen provides a path that is as elegant as it is challenging—a path walked with open eyes, an open heart, and empty hands.