The invention of writing marks one of the most transformative events in human history. It is the bridge between prehistory and recorded history, enabling the transmission of knowledge across generations, the administration of complex societies, and the flowering of literature, science, and philosophy. Writing was not invented in a single moment or place, but rather emerged independently in various regions of the world, each adapting the system to suit local languages, needs, and cultures. This essay explores the origins, evolution, and significance of writing, tracing its journey from primitive pictographs to the complex scripts that shape modern communication.

Precursor to Writing: Symbols and Proto-writing

Before true writing systems were developed, early humans used various forms of symbolic representation. These symbols, found in cave paintings, carvings, and early artifacts, date back tens of thousands of years. For example, the cave art at Lascaux in France and Chauvet in southern Europe includes not just images of animals but also abstract signs that may have conveyed information or held spiritual meaning.

Around 8000 BCE, as agriculture emerged and human societies became more sedentary, the need for record-keeping grew. In Mesopotamia, early Neolithic peoples used clay tokens to represent goods such as grain, livestock, or oil. These tokens were used in trade and accounting, often stored in sealed clay envelopes. Over time, people began impressing the shapes of the tokens onto the outside of the envelopes, leading to the idea of representing objects with marks on a flat surface—an early step toward writing.

The Birth of Writing in Mesopotamia

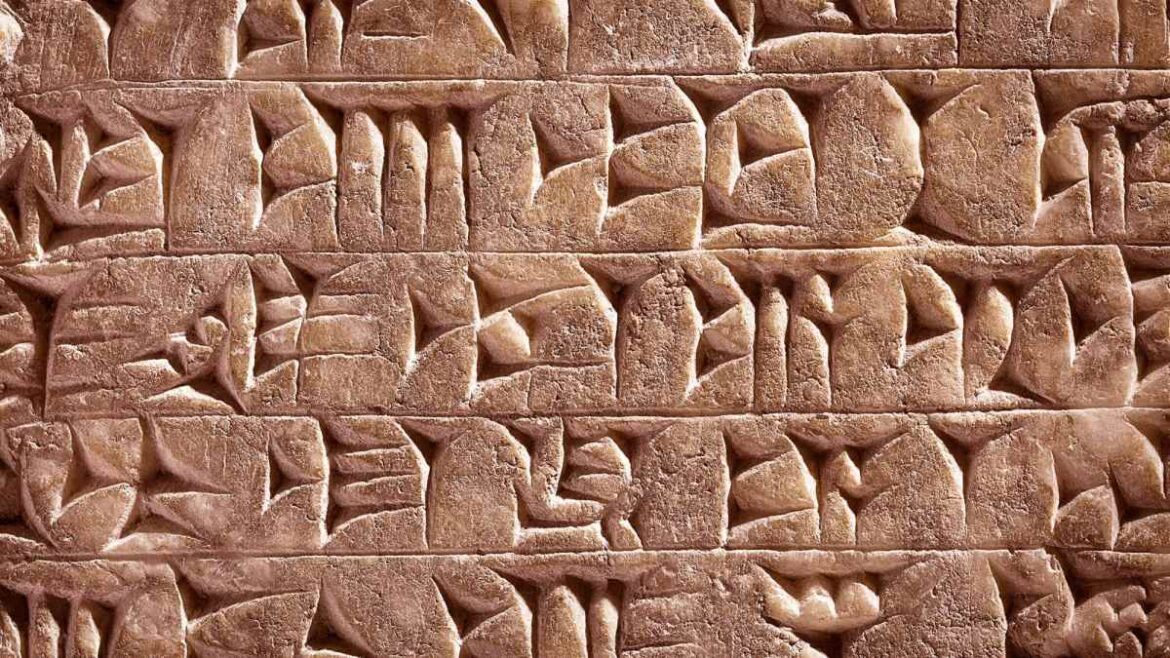

The first true writing system is generally credited to the Sumerians of ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq), who developed cuneiform around 3200 BCE. The word “cuneiform” comes from the Latin cuneus, meaning “wedge,” referring to the wedge-shaped marks made with a stylus on clay tablets. Initially, cuneiform was pictographic—symbols directly represented objects or concepts. For example, a drawing of a fish represented a fish.

Over time, these pictograms became more abstract and stylized, allowing scribes to represent sounds and grammatical elements, not just concrete objects. This transition from pictographs to phonetic writing (symbols representing syllables or sounds) marked a major innovation. With phonetic writing, it became possible to write any word or idea, even those not easily depicted visually.

The development of cuneiform was closely tied to the needs of temple economies and state administration. It allowed for the keeping of detailed records—lists of goods, land transactions, tax records, and legal codes. The Code of Ur-Nammu and later the Code of Hammurabi are among the earliest known examples of codified law.

Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Around the same time as cuneiform, a distinct writing system emerged in ancient Egypt—hieroglyphics. Appearing around 3100 BCE, Egyptian hieroglyphs combined logographic (word-based), syllabic, and alphabetic elements. Like cuneiform, the earliest uses of hieroglyphs were administrative and ceremonial, recording the deeds of kings, religious rituals, and temple offerings.

Unlike cuneiform, which was written on clay, hieroglyphs were carved into stone or written on papyrus. Papyrus, made from the papyrus plant, offered a more portable medium and helped promote writing’s use in various aspects of Egyptian life, including literature, science, and correspondence.

Writing in the Indus Valley

The Indus Valley Civilization, which flourished around 2600–1900 BCE in present-day Pakistan and northwest India, also developed a script, often referred to as the Indus script. Hundreds of short inscriptions have been found on seals, tablets, and pottery. Despite extensive study, the Indus script remains undeciphered, and it is unclear whether it was a full writing system or a form of proto-writing. Nonetheless, its existence attests to the importance of symbolic communication in early urban societies.

Chinese Characters and Early Writing in East Asia

In China, the earliest known form of writing appeared during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE) in the form of oracle bone script. These were inscriptions carved into animal bones or turtle shells used in divination rituals. The characters are recognizable ancestors of modern Chinese script and include both pictographic and ideographic elements.

Unlike the phonetic systems of the West, Chinese writing developed into a logographic system, where each character represents a word or morpheme. This system, although highly complex, proved extremely durable. Chinese characters remain in use today, with significant continuity stretching back over three thousand years.

The Alphabet: A Revolutionary Innovation

Perhaps the most revolutionary step in the history of writing was the development of the alphabet. The earliest known alphabetic script was the Proto-Sinaitic script, which emerged around 1800 BCE in the Sinai Peninsula. This system evolved from Egyptian hieroglyphs and used symbols to represent consonantal sounds, drastically reducing the number of symbols needed to write a language.

The Phoenicians, a seafaring people based in present-day Lebanon, refined this idea into a true alphabet around 1050 BCE. Their script consisted of 22 consonantal letters and could be used to write multiple languages. The Phoenician alphabet spread widely through trade and cultural exchange, influencing the Greek alphabet, which added vowels.

From the Greek alphabet came Latin, Cyrillic, and other scripts. The Latin alphabet, in particular, became the foundation of writing in much of Europe and the Americas. The simplicity and adaptability of alphabetic writing made literacy more accessible and greatly expanded the use of writing in everyday life.

The Role of Writing in Civilization

The invention of writing had profound implications for human society. It allowed for the accumulation and transmission of knowledge, making it possible for later generations to build upon the discoveries and experiences of the past. Writing enabled the creation of complex legal codes, religious texts, historical records, literature, and scientific works.

In ancient societies, scribes held prestigious positions, as literacy was limited to a small elite. Written records helped rulers maintain control over vast territories and populations. Empires like those of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China relied on written communication for administration, taxation, and law enforcement.

Religions also flourished with writing. Sacred texts like the Hebrew Bible, the Vedas, the Quran, and the Buddhist sutras preserved spiritual teachings and traditions, allowing them to spread across regions and centuries.

Writing and the Modern World

With the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, writing entered a new era. Books became more widely available, literacy spread, and the modern world took shape. The Renaissance, Reformation, and Enlightenment were all powered by the written word.

Today, writing is ubiquitous—from handwritten notes and printed books to digital messages and programming code. It remains one of the most powerful tools of human expression, learning, and communication.

Technological advancements, particularly the advent of computers and the internet, have transformed writing again. Text can now be produced, edited, shared, and accessed instantly across the globe. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are even generating new forms of written content.

Conclusion

The invention of writing is not just a technological breakthrough; it is a cornerstone of civilization. From ancient pictographs to modern digital texts, writing has enabled humanity to document its thoughts, preserve its culture, and shape its future. It is the thread that connects past to present, allowing us to understand history, express identity, and envision new possibilities. As we continue to evolve in the digital age, writing remains as vital as ever—proof of humanity’s enduring need to communicate, to remember, and to create.