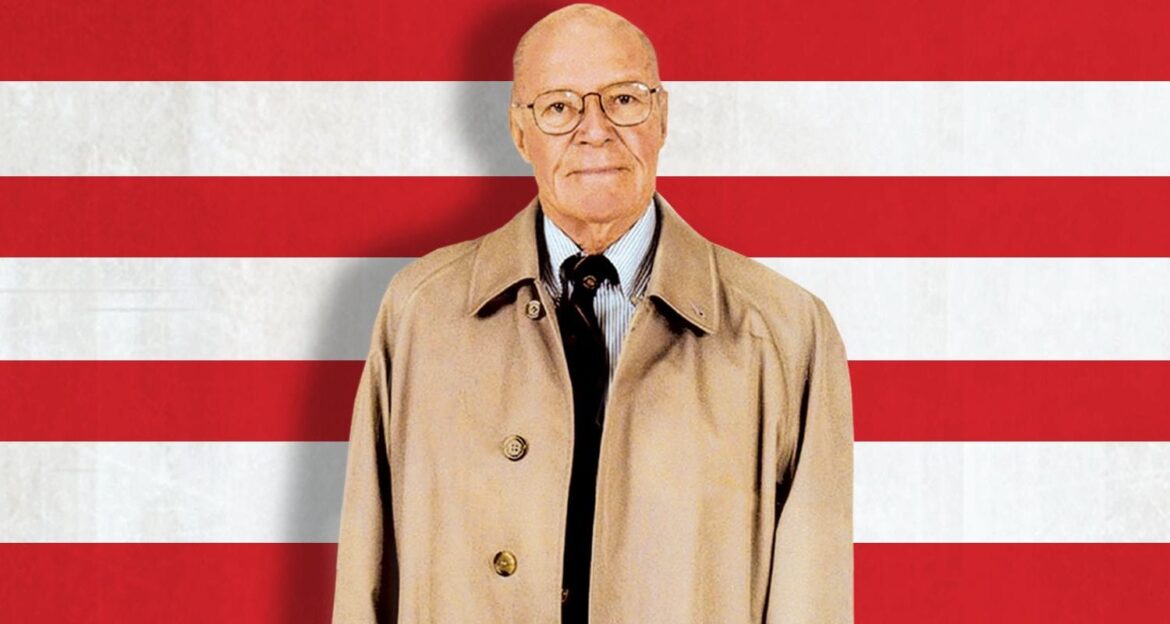

Few documentaries capture the complex interplay between war, politics, and human psychology as profoundly as The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (2003). Directed by the legendary filmmaker Errol Morris, this Academy Award-winning documentary provides an intimate portrait of Robert S. McNamara, the former U.S. Secretary of Defense under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, and his reflections on some of the most turbulent periods of the 20th century. The film blends historical footage, interviews, and Morris’s distinctive cinematic techniques to explore the moral and strategic complexities of modern warfare, making it not only a biography but a meditation on the human condition during times of conflict.

Robert McNamara: From Numbers to Decisions

Robert S. McNamara was a man defined by his intellect and his relentless pursuit of data-driven solutions. Before entering government service, he was a successful executive at the Ford Motor Company, where he revolutionized management through statistical analysis and efficiency studies. This quantitative mindset would later shape his tenure as Secretary of Defense, earning him both admiration and criticism. McNamara’s story, as told in The Fog of War, is emblematic of the tension between rationality and morality, between cold logic and human consequences.

The documentary takes viewers through key moments of McNamara’s career, from the strategic planning of World War II bombing campaigns to the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the controversial escalation of the Vietnam War. Through these experiences, McNamara reflects on the lessons he learned, offering insights that resonate far beyond military history. His frank self-examination and willingness to confront uncomfortable truths make the film a rare example of historical introspection.

The Eleven Lessons

The film is structured around eleven lessons that McNamara shares from his life and career. Each lesson serves as a philosophical and ethical lens through which viewers can understand the complexities of leadership, decision-making, and warfare.

1. Empathize with Your Enemy – McNamara begins with the idea that understanding one’s adversary is crucial. He recounts the Cuban Missile Crisis, highlighting how empathy and seeing the world from the Soviet perspective helped avoid nuclear catastrophe. This lesson underscores the necessity of perspective in conflict resolution, reminding us that misperception and misunderstanding often escalate tensions unnecessarily.

2. Rationality Will Not Save Us – Despite his reliance on data and analysis, McNamara acknowledges that rationality alone cannot prevent disasters. Human behavior, politics, and chance introduce uncertainty that cannot always be quantified. This lesson challenges the assumption that intelligence and planning are sufficient safeguards against war’s chaos.

3. There’s Something Beyond Oneself – Leadership demands recognition that decisions have consequences beyond personal ambition or ideology. McNamara’s reflections reveal the weight of responsibility carried by those in positions of power and the ethical imperative to consider the lives affected by policy decisions.

4. Maximize Efficiency – McNamara’s background in management informs this lesson, but he tempers it with caution. Efficiency in bureaucracies and military operations can be dangerous if divorced from moral consideration. He reflects on the firebombing of Japanese cities during World War II, acknowledging that technological precision did not mitigate the human cost.

5. Proportionality Should Be a Guiding Principle – This lesson addresses the ethics of military action. McNamara grapples with the idea that the use of force must be proportionate to the threat or objective, a principle often violated in modern warfare. The Vietnam War, in particular, exemplified how excessive force and misjudged strategies lead to prolonged suffering.

6. Get the Data – McNamara emphasizes the importance of gathering information before making decisions, a principle he applied throughout his career. Yet he also warns of the limitations of data—statistics cannot capture the full human and moral dimension of war.

7. Belief and Seeing Are Often Both Wrong – Human perception is fallible, and leaders must remain humble in the face of uncertainty. McNamara recounts instances where policymakers acted on flawed assumptions, illustrating how cognitive biases and misjudgments can have catastrophic consequences.

8. Be Prepared to Reexamine Your Reasoning – Flexibility and humility are essential in leadership. McNamara stresses that clinging to preconceived notions, especially during crises, can worsen outcomes. His own acknowledgment of mistakes in Vietnam exemplifies the need for continuous reassessment of strategy.

9. In Order to Do Good, You May Have to Do Bad – This is perhaps the most morally challenging lesson. Leaders sometimes make decisions that cause harm to achieve a greater objective. McNamara reflects on the difficult moral calculus involved in wartime decision-making, confronting the tension between ethical principles and strategic imperatives.

10. Never Say Never – McNamara observes that history is unpredictable and that rigid thinking can be dangerous. Adaptability and open-mindedness are critical in navigating complex situations, especially in international relations.

11. You Can’t Change Human Nature – Finally, McNamara acknowledges the enduring presence of human flaws—greed, fear, ambition, and prejudice—that influence decisions and outcomes. Despite technological advances and strategic innovations, the fundamental challenges of human behavior remain.

Cinematic Approach and Impact

Errol Morris’s directorial style significantly enhances the documentary’s impact. Using his signature “Interrotron” technique, Morris captures McNamara’s reflections with an intimacy and intensity that conventional interviews cannot achieve. The technique allows McNamara to look directly into the camera while speaking, creating a sense of direct communication with the audience. This enhances the emotional weight of his confessions and reflections, making the lessons feel personal and immediate.

The film’s use of archival footage, photographs, and declassified documents immerses viewers in the historical context of McNamara’s career. From the devastation of Tokyo and Hiroshima to tense standoffs with the Soviet Union, the visuals reinforce the gravity of the decisions McNamara discusses. The juxtaposition of visual evidence with reflective commentary creates a layered understanding of history—one that acknowledges both strategy and human suffering.

Ethics, Accountability, and the Human Cost

A central theme of The Fog of War is accountability. McNamara does not shy away from his role in controversial military actions, most notably the escalation of the Vietnam War. His candid admissions about mistakes, misjudgments, and unintended consequences serve as a meditation on the responsibilities of leadership. The film challenges viewers to consider the ethical dimensions of decision-making, especially when the stakes involve human life on a massive scale.

The documentary also confronts the tension between efficiency, strategy, and morality. McNamara’s reliance on statistical models and management principles illustrates the potential dangers of detaching analysis from ethical considerations. The Fog of War encourages reflection on how societies and leaders can balance pragmatism with humanity, reminding us that the consequences of decisions extend far beyond the immediate objectives.

Lessons for Today

While the film focuses on historical events, its lessons are timeless. In an era marked by geopolitical tensions, nuclear proliferation, and complex global challenges, McNamara’s insights remain profoundly relevant. Leaders, policymakers, and citizens alike can draw lessons about empathy, humility, adaptability, and the moral dimensions of decision-making. Moreover, the documentary serves as a reminder of the human cost of conflict and the importance of learning from history to prevent repeating past mistakes.

Conclusion

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara is more than a documentary—it is a profound exploration of human nature, leadership, and the ethical complexities of war. Through Errol Morris’s masterful direction and McNamara’s candid reflections, the film invites viewers to grapple with difficult questions about morality, strategy, and accountability. Each of the eleven lessons offers insight not only into historical events but also into timeless truths about human behavior and the responsibilities that come with power.

Ultimately, the documentary challenges us to reflect on our own perspectives, decisions, and assumptions. It reminds us that history is shaped by both human ambition and human error, and that understanding the past is essential to navigating the future. By combining historical analysis, personal reflection, and cinematic artistry, The Fog of War stands as a landmark achievement in documentary filmmaking and a vital resource for anyone seeking to understand the intricate, often painful realities of war and leadership.

Through its exploration of McNamara’s life and lessons, the film underscores a sobering truth: that war is never merely a matter of strategy or statistics, but a profoundly human enterprise, fraught with moral dilemmas, unforeseen consequences, and the enduring need for empathy, humility, and reflection.