An Exploration of Surrealism, Spirituality, and Revolutionary Vision

Salvador Dalí’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951) is one of the most iconic and evocative religious paintings of the 20th century. Despite being created by a man best known for his surrealist work and eccentric personality, this painting is a powerful, almost classical representation of Christ’s crucifixion — yet one that defies traditional perspectives and expectations. The work stands as a unique convergence of Dalí’s surrealism, scientific interest, and newfound religious sentiment. Its historical, artistic, and spiritual significance make it a rich subject for analysis and discussion.

The Painting: A Description

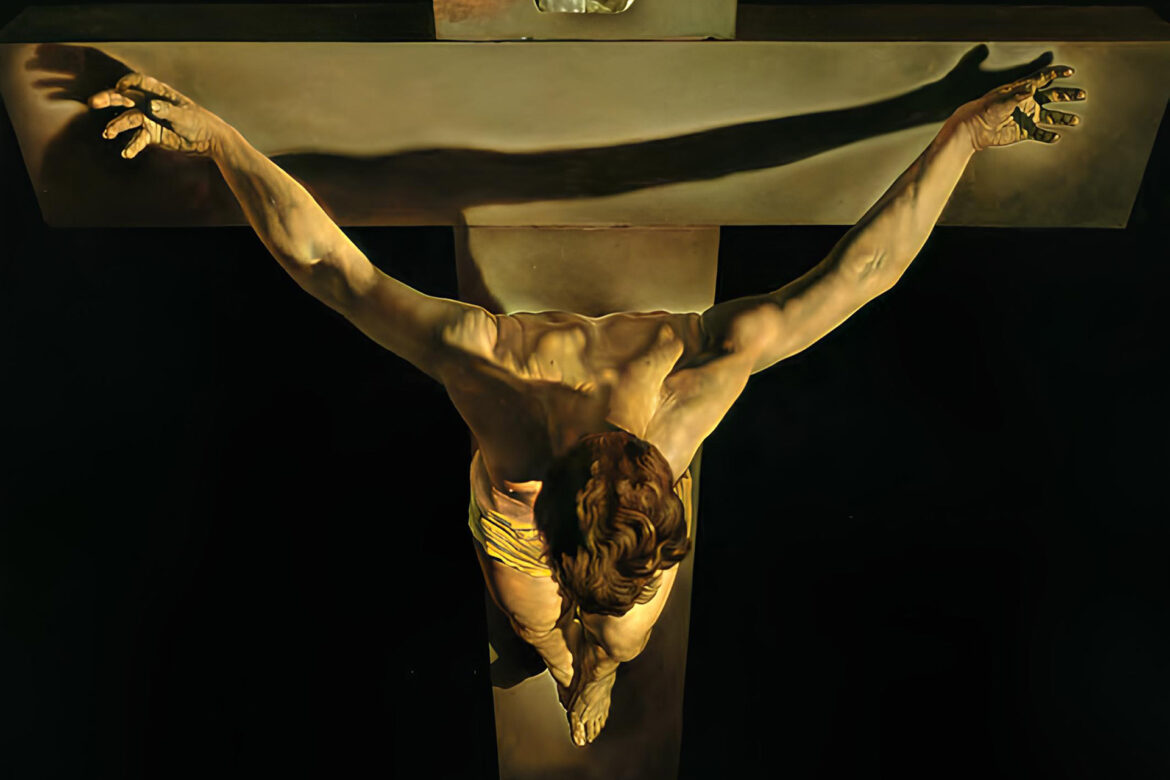

Christ of Saint John of the Cross depicts Jesus Christ on the cross, viewed from an unusual and dramatic aerial perspective. The cross floats in a dark, clouded sky above a tranquil body of water, likely referencing the Bay of Port Lligat in Catalonia, where Dalí lived. Below, two fishermen go about their work near a boat, oblivious to the divine presence above them. Christ’s body is elongated and idealized, hanging in a graceful pose with no crown of thorns, no blood, and no nails visibly piercing his hands or feet. The scene is infused with serenity rather than suffering, with Christ portrayed as a transcendent and divine figure rather than a tortured human.

Dalí’s composition is based on a 16th-century sketch by the Spanish mystic Saint John of the Cross, who claimed to have seen the image in a vision. The sketch, though small and simple, showed Christ from above, looking down at the cross — an unusual vantage point that inspired Dalí to reimagine the crucifixion with dramatic force and modern technique.

Artistic Techniques and Composition

Dalí employed meticulous realism in this painting, a style he referred to as “nuclear mysticism,” combining classical techniques with a surrealist vision shaped by developments in modern physics. He believed that atomic theory and quantum mechanics revealed new layers of divine order in the universe, which could be explored through art. In Christ of Saint John of the Cross, Dalí drew upon the principles of geometry and symmetry. The triangle formed by Christ’s arms and the circle implied by his head and halo invoke classical harmony, and also reference Christian symbolism: the triangle representing the Holy Trinity and the circle symbolizing eternity.

The perspective is perhaps the most striking element of the painting. By placing the viewer above and slightly behind Christ, Dalí inverts the traditional depiction of the crucifixion, which usually places the viewer on the ground, looking up at Christ. This “God’s eye view” invites contemplation not only of Christ’s divinity but of the cosmic scale of sacrifice. Christ is suspended between heaven and earth — a bridge between the spiritual and the mundane.

Departure from Traditional Religious Imagery

Although Dalí had long been associated with surrealism and avant-garde movements that often critiqued or even mocked religion, this painting marks a departure into a more spiritual and reverent realm. Dalí had returned to the Catholic faith in the 1940s, partly due to the trauma and chaos of World War II, and this renewed faith is evident in Christ of Saint John of the Cross.

Yet Dalí’s interpretation remains unconventional. There is a conspicuous absence of the traditional instruments of Christ’s passion — no nails, no crown of thorns, no visible wounds. Dalí explained that he had a dream in which he saw Christ in this form, and was convinced that the depiction of Christ without physical pain or blood would be more spiritually powerful and aesthetically uplifting. This decision sparked controversy among critics and religious observers alike, but for Dalí, it was a way to emphasize Christ’s divine nature over his human suffering.

Controversy and Public Reaction

Upon its unveiling in 1951, the painting was met with controversy. The Glasgow Museums purchased it for £8,200 — a significant sum at the time — under the directorship of Tom Honeyman. The acquisition was criticized by many who believed the museum should not be spending public funds on modern art, especially from a figure as polarizing as Dalí. Some artists and critics denounced it as kitsch or overly sentimental. However, over time, the painting became one of the most beloved and visited artworks in the museum’s collection.

In fact, Christ of Saint John of the Cross has since become emblematic of the city of Glasgow’s commitment to cultural richness and openness to diverse artistic expressions. It is regularly cited as one of the most popular paintings in the United Kingdom, drawing both religious pilgrims and lovers of modern art.

Dalí’s Personal Symbolism

Dalí was a complex character whose work often incorporated elements of his personal mythology, obsessions, and psychological interests. While Christ of Saint John of the Cross appears at first glance to be a relatively straightforward religious image, it contains elements that are deeply personal to Dalí. The landscape below the crucifixion is based on Port Lligat, the village where Dalí spent much of his life and created many of his greatest works. By placing Christ above his familiar world, Dalí seems to be fusing the divine and the personal, suggesting that spiritual truth is not distant but embedded within one’s own experience of the world.

Furthermore, Dalí’s fascination with the intersection of science and religion is crucial to understanding this painting. He was deeply interested in the atomic age and believed that modern science could lead humanity closer to understanding the divine. This painting was part of a broader movement within Dalí’s later career to reconcile the mystical and the material — to use the tools of realism and scientific thinking to express spiritual truths.

Legacy and Influence

Christ of Saint John of the Cross holds a unique place in the history of art. It represents a moment when a leading modernist artist turned toward classical beauty and religious tradition, but did so with a distinctly modern lens. Dalí’s work influenced not only other painters but also filmmakers, writers, and philosophers interested in the connections between mysticism, art, and science.

The painting continues to spark dialogue among theologians, art historians, and cultural critics. It challenges viewers to reconsider their assumptions about suffering, beauty, divinity, and artistic expression. It also serves as a reminder that even the most avant-garde artists are capable of creating works that speak to eternal human concerns — love, sacrifice, redemption, and the search for meaning.

In sum, Salvador Dalí’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross is much more than a religious painting; it is a philosophical statement, an artistic experiment, and a spiritual vision. By marrying surrealist technique with classical inspiration and mystical insight, Dalí created a masterpiece that transcends time and genre, offering a haunting and transcendent view of the divine.