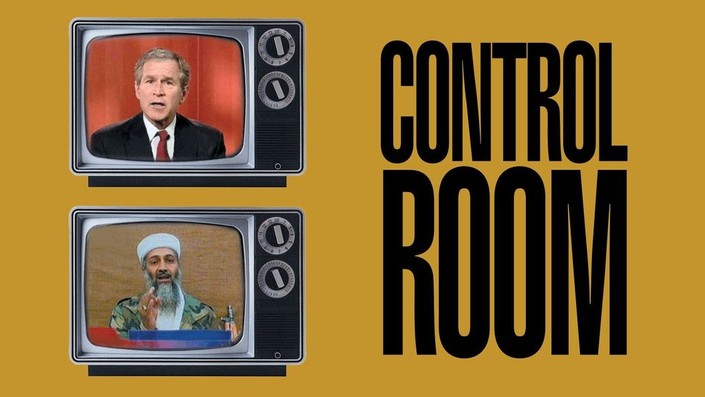

When we think of war, we often picture soldiers, explosions, and front-line combat. But in the modern age, every war is also fought through images, words, and the framing of truth itself. Few documentaries have captured this reality as sharply and provocatively as Control Room (2004), directed by Jehane Noujaim.

Set during the early stages of the Iraq War in 2003, Control Room offers a behind-the-scenes look at the Arabic news network Al Jazeera and its interactions with U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), located at Qatar’s Al Udeid Air Base. The film does not simply chronicle military events; it exposes the media war — the competition between Western and Arab perspectives to define what the conflict means and who controls its narrative.

Through intimate interviews, candid conversations, and raw footage, Control Room examines how news is filtered, framed, and contested. It reveals that in war, truth is not absolute — it’s a construct shaped by bias, power, and perspective.

A Different Kind of Battlefield

The documentary begins in the months leading up to the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. American and coalition forces have set up a media hub at CENTCOM, where hundreds of international journalists are based. Among them are correspondents from Al Jazeera, a network already known for airing controversial footage and for being accused by the U.S. government of “anti-American bias.”

From the start, the film places us in the middle of a clash of ideologies. On one side are U.S. military officials and Western journalists who see the invasion as a mission to liberate Iraq and bring democracy. On the other are Arab journalists who see the war as an act of aggression and imperialism.

Jehane Noujaim doesn’t take sides. Instead, she observes the tension as it unfolds. Her camera captures the daily operations at Al Jazeera’s newsroom, where producers and reporters scramble to verify information amidst the chaos of war. It also follows American military spokespersons as they attempt to control the message coming out of Iraq — to shape what the world sees and hears.

The result is a fascinating portrait of how media and military power intersect, and how both sides — often unknowingly — become participants in the propaganda machine.

Al Jazeera: Challenging the Western Lens

One of the film’s most compelling achievements is its humanization of Al Jazeera’s journalists. In 2003, the network was still widely misunderstood in the West. Many Americans, influenced by official rhetoric, associated it with terrorist sympathies or sensationalist reporting.

But Control Room reveals a far more nuanced reality. Al Jazeera’s staff members are professional, intelligent, and deeply committed to their work. They are also frustrated — not because they oppose the U.S. military per se, but because they feel that the Western media deliberately ignores or sanitizes the suffering of Iraqi civilians.

One of the most memorable figures in the documentary is Hassan Ibrahim, a British-educated Al Jazeera journalist who previously worked for the BBC. Ibrahim is articulate, witty, and deeply introspective. In one scene, he remarks, “We are accused of being pro-Saddam. We are accused of being anti-American. But we show both sides — the victims and the bombs. The problem is, the victims make people uncomfortable.”

That line encapsulates the heart of the film. Control Room argues that what we call “bias” often depends on where we stand. Western networks like CNN and Fox News emphasized the precision of American airstrikes and the heroism of soldiers. Al Jazeera, meanwhile, broadcasted the human toll — destroyed homes, weeping families, and civilian casualties. Both were reporting the truth, but from radically different angles.

The American Perspective: Loyalty and Doubt

The documentary also gives voice to the American side, particularly through Lieutenant Josh Rushing, a U.S. Marine Corps public affairs officer at CENTCOM. Initially, Rushing comes across as the embodiment of disciplined patriotism. He believes in his mission and in America’s role as a global force for good.

But as the film progresses, Rushing’s perspective begins to shift. Engaging in discussions with Al Jazeera journalists, he starts to question how the U.S. media presents the war — and whether Americans are truly getting the full story. His open-mindedness becomes one of the film’s moral anchors.

In one memorable exchange, Rushing admits that when Al Jazeera shows footage of Iraqi casualties, he feels anger at the network for portraying the U.S. negatively. But when he sees images of dead American soldiers, he feels sympathy — not outrage at the U.S. military. “That’s how empathy works,” he says, realizing the double standard that colors media on both sides.

This level of self-awareness is rare in war documentaries. It’s what gives Control Room its depth: it shows individuals struggling not only with external events but with their own evolving sense of truth and morality.

After the film’s release, Rushing’s honesty reportedly drew criticism from U.S. officials, and he later resigned from the military — a testament to how politically charged the documentary’s insights were at the time.

Truth in the Crossfire

Control Room was filmed at a time when the “information war” was just beginning to dominate global conflicts. The Iraq War was the first major war of the 24-hour news era, where every explosion, every speech, and every rumor could be broadcast in real time.

The film highlights how this immediacy can distort as much as it informs. When Al Jazeera aired footage of civilian deaths, U.S. officials accused it of fueling anti-American sentiment. When American networks aired footage of U.S. troops raising flags, Arab viewers accused them of glorifying occupation.

The truth, Control Room suggests, is somewhere in between — and perhaps impossible to pin down. In war, every image is political. Every omission is a choice.

The documentary’s most harrowing moment comes when an Al Jazeera journalist, Tareq Ayyoub, is killed in a U.S. airstrike on the network’s Baghdad bureau. His colleagues are devastated, convinced that the attack was intentional — an effort to silence their reporting. The Pentagon denies this, calling it a tragic mistake.

Regardless of intent, the incident underscores the film’s central message: that journalists are not passive observers of war. They are participants, vulnerable to the same dangers and moral complexities as soldiers.

Style and Substance: Jehane Noujaim’s Approach

Jehane Noujaim’s direction is subtle yet powerful. She never intrudes with narration or on-screen commentary. Instead, she builds tension through observation, allowing the audience to form their own conclusions. The film’s style is restrained but intimate, often capturing small gestures — a journalist lighting a cigarette, a soldier checking his watch, a quiet moment between interviews — that reveal the human cost of political conflict.

Noujaim’s approach mirrors the very idea she’s exploring: that truth is not imposed but discovered through perspective. By giving equal weight to both Al Jazeera and U.S. military voices, she turns Control Room into a dialogue rather than a debate. The viewer is invited to witness, not judge.

Media, Power, and the Question of Objectivity

At its core, Control Room asks one of the most pressing questions of our time: Can journalism ever be truly objective, especially in war?

Every network, whether Western or Arab, operates within political, cultural, and emotional frameworks that shape what it shows and what it leaves out. The film doesn’t accuse anyone of lying — instead, it reveals that bias is an inevitable consequence of perspective.

This makes Control Room timeless. Long after the Iraq War ended, its lessons continue to resonate in an era dominated by social media, disinformation, and competing narratives. The battle for truth, Noujaim shows, is no longer fought just with weapons, but with cameras, headlines, and algorithms.

Legacy and Reflection

Upon its release, Control Room was hailed as one of the most important documentaries of the early 21st century. It offered Western audiences a rare chance to see themselves through the eyes of the Arab world — not as liberators or villains, but as part of a complex global narrative shaped by competing truths.

In retrospect, the film feels prophetic. It anticipated the explosion of media polarization that would define the following decades. Watching it today, one cannot help but think of how digital echo chambers and partisan news outlets have only deepened the divisions it exposed.

Yet, despite its heavy subject matter, Control Room is not cynical. It is, in many ways, a film about hope — about the possibility of dialogue and understanding even amid war. Figures like Josh Rushing and Hassan Ibrahim remind us that empathy and curiosity can bridge seemingly unbridgeable divides.

Conclusion: The War We Still Fight

In the end, Control Room is not just a film about Iraq, or even about Al Jazeera. It’s about the war for truth that underlies every conflict — the struggle to define reality in a world where every story has two sides and every image has an agenda.

Jehane Noujaim’s documentary remains a powerful reminder that information itself is a weapon — one capable of liberating minds or deepening divisions. In showing both sides of the lens, she forces us to question our own assumptions about what we see, believe, and share.

For viewers seeking to understand not only the Iraq War but the nature of modern media itself, Control Room is essential. It challenges us to think critically, to listen across divides, and to recognize that even in the fog of war, there are still those trying — against all odds — to tell the truth.