When Blade Runner premiered in 1982, it wasn’t an instant hit. Critics were divided, audiences were confused, and the film’s box office performance was underwhelming. Yet over time, Ridley Scott’s adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? transformed into one of the most influential science fiction films ever made. Today, it stands as a cornerstone of cinematic history, shaping the cyberpunk genre and redefining the way we imagine the future.

With its rain-soaked streets, neon-lit skyscrapers, and morally complex story, Blade Runner is far more than a simple sci-fi detective tale. It’s a meditation on identity, humanity, and the blurred line between artificial and real life.

Setting the Stage – Los Angeles, 2019

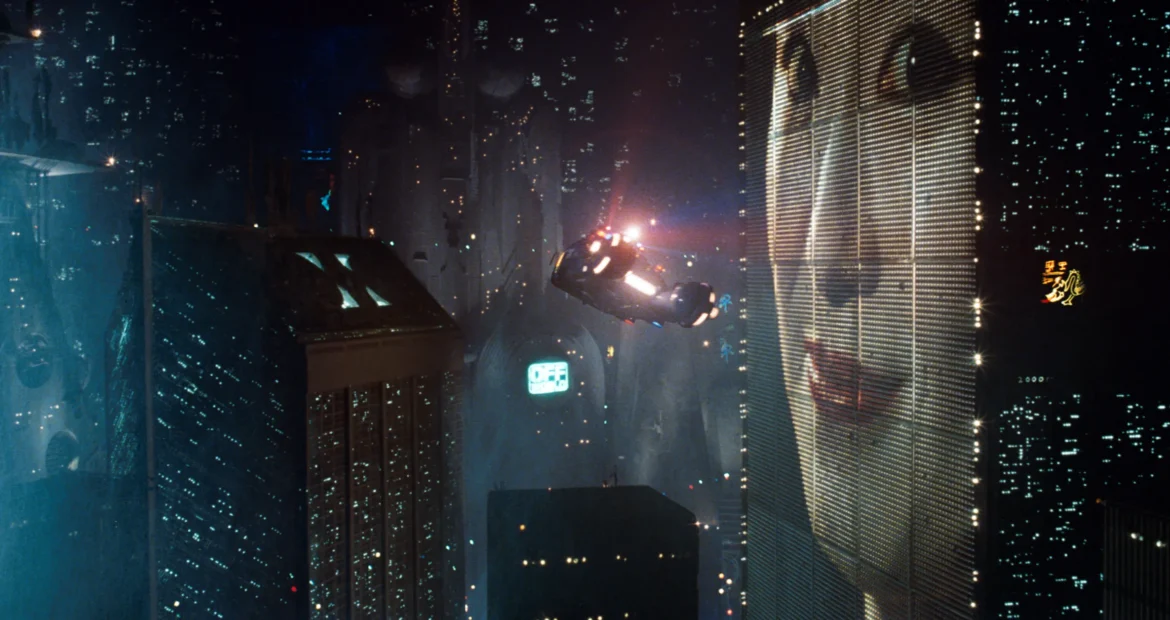

Blade Runner takes place in a dystopian Los Angeles in the year 2019—a sprawling, decayed metropolis lit by endless advertisements and plagued by perpetual rain. The city is a melting pot of cultures, dominated by Asian street markets, giant corporate towers, and omnipresent consumerism. Environmental collapse has forced many humans to emigrate to off-world colonies, leaving behind a grim, overpopulated Earth.

In this future, the Tyrell Corporation manufactures bioengineered humans known as replicants. These replicants are physically superior to humans but emotionally underdeveloped. They are used for dangerous or undesirable work in off-world colonies and are forbidden on Earth. When rogue replicants return, they are hunted down and “retired” by special police officers known as Blade Runners.

The Story – A Noir Detective in a Sci-Fi World

Harrison Ford plays Rick Deckard, a former Blade Runner reluctantly pulled out of retirement to hunt down a group of escaped Nexus-6 replicants. Led by the charismatic but deadly Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), these replicants have returned to Earth in search of a way to extend their artificially short four-year lifespans.

Deckard’s investigation takes him deep into the underbelly of the city, from smoky nightclubs to abandoned buildings. Along the way, he meets Rachael (Sean Young), a Tyrell Corporation employee who is unaware she is a replicant. Rachael’s implanted memories make her believe she is human, blurring the line between reality and fabrication.

As Deckard tracks the replicants one by one, he begins to question his own role in their destruction. These replicants are not simple machines—they display fear, love, and a desperate will to survive. The hunter becomes morally entangled with his prey, and the film builds toward a confrontation that is as emotional as it is philosophical.

Themes and Questions

Blade Runner operates on multiple thematic levels, which is one reason it has inspired decades of discussion.

What Does It Mean to Be Human?

The central question of the film is whether humanity is defined by biology or by behavior. The replicants, though artificial, display more emotional depth than many of the humans in the story. They form bonds, show empathy, and long for life. In contrast, most humans in the film are cold, detached, and morally compromised.

Deckard himself becomes a mirror for the audience—questioning whether his job is just, and possibly even questioning his own nature. The film never definitively answers whether Deckard is human or a replicant, leaving that ambiguity for viewers to debate.

Memory and Identity

Rachael’s realization that her memories are artificial raises profound questions about identity. If our experiences and emotions are shaped by memories, does it matter if those memories are “real” or manufactured? This idea cuts to the core of what makes someone who they are.

Mortality and the Value of Life

Roy Batty’s quest to extend his life mirrors the human fear of death. His final moments, in which he chooses to save Deckard rather than kill him, reveal a deep capacity for empathy. The now-famous “Tears in Rain” monologue, largely improvised by Rutger Hauer, crystallizes the film’s meditation on mortality.

Visual Style – A Masterpiece of World-Building

Ridley Scott’s vision of Los Angeles in 2019 is perhaps the most influential aspect of Blade Runner. The film’s production design, by Lawrence G. Paull and Syd Mead, blends elements of film noir, industrial decay, and futuristic technology into a seamless, lived-in world.

The streets are drenched in rain, choked with smog, and illuminated by garish neon lights. Advertising blimps float overhead, broadcasting cheerful propaganda to contrast the grim reality below. The Tyrell Corporation’s headquarters rise like modern pyramids above the city, symbolizing power and control.

Scott pioneered a layered visual style that made the world feel inhabited and functional, not just a backdrop. This level of detail inspired countless other films, TV shows, and video games—from The Matrix to Cyberpunk 2077.

Music – The Sound of a Future Dream

The electronic score by Vangelis is an essential part of Blade Runner’s atmosphere. Combining synthesizers with jazz and orchestral elements, the music feels both futuristic and melancholic. It perfectly mirrors the film’s blend of high-tech wonder and deep emotional resonance.

Vangelis’ themes range from the haunting love motif for Deckard and Rachael to the swelling, almost sacred sounds accompanying the cityscape shots. The music has since become iconic, influencing electronic music for decades.

Reception – From Cult Film to Classic

Upon release, Blade Runner received mixed reviews. Some critics found it slow and overly stylized, while others praised its visual artistry. The theatrical cut also included a studio-mandated voiceover narration by Ford and a more optimistic ending—choices that Scott later regretted.

Over the years, the film’s reputation grew, fueled by the release of alternate cuts. The Director’s Cut in 1992 removed the voiceover and ambiguous ending, while the Final Cut in 2007 restored Scott’s preferred vision with enhanced effects and sound. These versions helped solidify Blade Runner as a masterpiece of science fiction cinema.

Influence and Legacy

Blade Runner’s influence can be seen in nearly every corner of the cyberpunk genre and beyond. Its depiction of a dystopian, multicultural megacity became the template for future visions of urban life. Its philosophical questions about artificial intelligence resonate even more strongly today, as real-world AI becomes increasingly sophisticated.

The film’s combination of noir storytelling, philosophical depth, and visual innovation paved the way for other cerebral science fiction films, such as Ghost in the Shell, Dark City, and Ex Machina.

The story also continued in Blade Runner 2049 (2017), directed by Denis Villeneuve. While set decades later, the sequel maintained the original’s thoughtful tone and visual beauty, deepening the exploration of identity and memory.

The Final Scene – Tears in Rain

Perhaps the most enduring moment in Blade Runner is Roy Batty’s death scene. After a tense chase through a derelict building, Batty saves Deckard from falling to his death. Sitting in the rain, he delivers his famous monologue:

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe… All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.”

In this moment, Batty transcends the role of antagonist. He becomes a tragic figure who has seen wonders, loved life, and accepts his mortality with grace. His act of mercy toward Deckard suggests that the capacity for humanity lies not in one’s origin, but in one’s choices.

Conclusion – A Timeless Reflection on Humanity

Blade Runner endures because it is more than a science fiction detective story—it is a meditation on what it means to be alive. It presents a future that feels disturbingly real, yet filled with moments of profound beauty.

By merging the aesthetics of film noir with cutting-edge science fiction, Ridley Scott created a timeless world that continues to captivate and inspire. Its themes of identity, morality, and mortality remain as relevant in our age of AI as they were in 1982.

In the end, Blade Runner asks us to look at the world—and ourselves—with fresh eyes. Are we defined by our biology, our memories, or our actions? Do we value life because it is fleeting? And in a world where artificial beings can feel love and sorrow, what truly separates the human from the machine?

Perhaps, as the rain falls and the neon lights flicker, the line between the two was never as clear as we thought.