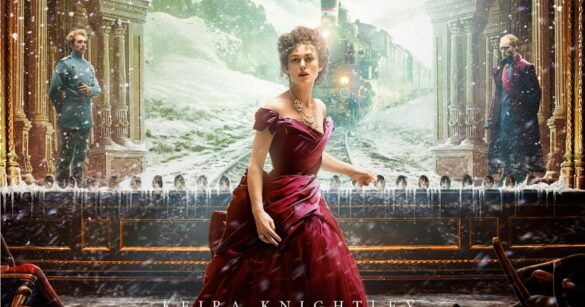

Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina (2012) is a visually daring and emotionally rich adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s timeless 1877 novel. Starring Keira Knightley as Anna and Jude Law as her husband, Alexei Karenin, the film reimagines one of literature’s greatest tragedies within a world that is both theatrical and surreal. Unlike traditional adaptations, Wright boldly stages much of the action as if it were taking place within a theatre — with moving sets, curtains, and shifting backdrops — a metaphor for the artificiality, performance, and repression of Russian high society in the late 19th century.

The film, which also stars Aaron Taylor-Johnson as Count Vronsky, Matthew Macfadyen as Oblonsky, and Domhnall Gleeson as Levin, brings Tolstoy’s complex moral and emotional landscape to life in a way that feels both grand and intimate. It is a film about love — not merely romantic love, but the different forms it can take: passionate, moral, spiritual, and destructive.

Plot Overview

Set in Imperial Russia during the 1870s, the story opens with a scandal. Prince Stepan Oblonsky (Matthew Macfadyen) has been caught in an affair with his children’s governess, shattering his marriage to Dolly (Kelly Macdonald). To help mediate, Oblonsky’s sister Anna (Keira Knightley), the wife of high-ranking government official Alexei Karenin (Jude Law), travels from St. Petersburg to Moscow.

On the train journey, Anna meets Countess Vronskaya and her charming son, Count Alexei Vronsky (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). When they arrive in Moscow, Anna also meets Kitty (Alicia Vikander), a young woman in love with Vronsky. But when Vronsky becomes captivated by Anna, Kitty’s romantic hopes are crushed, setting off a chain of heartbreaks and moral entanglements.

Anna initially resists her attraction to Vronsky, but their chemistry proves irresistible. Despite being married and a mother, she embarks on an affair that shocks the aristocracy. While Vronsky offers her freedom and passion, society condemns her. Karenin, though humiliated, maintains his composure and refuses to divorce her outright, fearing scandal.

As their love affair deepens, Anna becomes increasingly isolated — rejected by polite society, estranged from her son, and tormented by jealousy and insecurity. Meanwhile, in a parallel story, the idealistic landowner Konstantin Levin (Domhnall Gleeson) struggles with his love for Kitty and his quest for moral and spiritual purpose. His grounded, authentic life in the countryside contrasts sharply with the artificial glamour and decay of aristocratic St. Petersburg.

The story culminates in tragedy. Consumed by despair, paranoia, and alienation, Anna takes her own life by throwing herself under a train — the same train that symbolized her fateful meeting with Vronsky. The film closes with Levin finding peace and meaning through simplicity, love, and honest labor — the moral counterpoint to Anna’s tragic passion.

Character Analysis

Anna Karenina

Keira Knightley delivers one of her finest performances as Anna. Her portrayal is at once regal, fragile, and emotionally raw. Anna is a woman caught between duty and desire, between societal expectation and the yearning for personal happiness.

At the beginning, she appears as the perfect wife and mother — elegant, admired, and respected. But beneath that composure lies restlessness and a hunger for real emotion. Her affair with Vronsky becomes both her liberation and her undoing. She experiences true passion but also loses her place in society, her child, and ultimately, her sense of self.

Wright’s Anna is not simply a victim of social hypocrisy; she is also a woman consumed by her own inner turmoil. As her relationship with Vronsky deteriorates, her love transforms into obsession and paranoia. Her final act — stepping in front of the train — is depicted not only as a moment of despair but also as an act of defiance against the rigid moral world that destroyed her.

Alexei Karenin

Jude Law’s portrayal of Karenin is restrained and deeply sympathetic. Traditionally depicted as cold and bureaucratic, Wright’s Karenin is instead a man of principle and quiet suffering. He loves Anna, even when she betrays him, and endures humiliation with dignity.

Karenin’s struggle is moral rather than emotional. He cannot comprehend the irrationality of passion, and his faith binds him to duty over feeling. His forgiveness of Anna after her near-death childbirth scene is one of the most moving moments in the film — a portrait of spiritual grace amid social cruelty.

Count Vronsky

Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s Vronsky embodies charm, vanity, and impulsiveness. Initially drawn to Anna’s beauty and sophistication, he mistakes desire for love. Though his affection is genuine, his immaturity and social privilege prevent him from understanding the depth of Anna’s sacrifice.

As their affair becomes increasingly suffocating, Vronsky’s passion wanes, and Anna’s insecurities grow. The imbalance between them mirrors the imbalance between male and female power in their world — a system that allows him to recover his reputation, while she is destroyed.

Konstantin Levin and Kitty

Levin’s story, often considered Tolstoy’s philosophical counterpart to Anna’s, represents an alternative path — a life rooted in honesty, nature, and moral clarity. Domhnall Gleeson’s gentle performance captures Levin’s introspective struggle between faith and doubt.

Kitty’s (Alicia Vikander) journey from naive romanticism to mature love parallels Anna’s, but with a happier resolution. Through their union, the film offers a glimpse of redemption — love that is patient, kind, and enduring, unlike the consuming fire of Anna’s passion.

Themes

Love and Desire

At the heart of Anna Karenina lies a meditation on love in all its forms: romantic, marital, spiritual, and destructive. Anna’s affair with Vronsky represents passion unfettered by morality or reason, a love that burns too brightly to last. Levin’s love for Kitty, by contrast, is grounded in truth and patience — love as commitment and moral harmony.

The film juxtaposes these two paths, suggesting that while passion can liberate, it can also consume. Love, in Tolstoy’s vision, is meaningful only when aligned with integrity and self-knowledge.

Society and Hypocrisy

Joe Wright’s decision to frame the film within a theatre serves as a powerful metaphor for society as performance. The aristocrats of St. Petersburg move like actors across a stage, their lives dictated by rules and appearances. The constant shifting of backdrops and props underscores how artificial and fragile their world is.

Anna’s tragedy is that she breaks the script. Her affair is not scandalous because it is immoral, but because it disrupts the social performance. The same society that tolerates male infidelity condemns female passion. The film exposes this hypocrisy — a world where image outweighs truth, and conformity is prized over authenticity.

Freedom and Confinement

Throughout the film, Anna struggles for freedom — freedom to love, to live honestly, to be herself. Yet every step toward liberation brings greater confinement. Her home, once elegant, becomes a cage; her relationship, once intoxicating, turns suffocating.

Wright visualizes this through constant framing: Anna is often enclosed by doorways, mirrors, or the theatre’s proscenium arch. Even her final moment — standing before the oncoming train — is framed as both an escape and an imprisonment, a release from the social machinery that has crushed her.

Faith, Morality, and Redemption

Levin’s storyline provides a moral and philosophical counterpoint to Anna’s descent. His struggle to reconcile reason and faith reflects Tolstoy’s own spiritual crisis. By the film’s end, Levin finds peace through simple virtues — love, family, and connection to the land — while Anna, alienated from both society and God, finds only destruction.

Coppola’s earlier films explored similar themes of isolation, but Anna Karenina treats them on a grand, cosmic scale. The film asks whether human beings can find meaning in a world governed by social conventions and moral ambiguity.

Visual and Aesthetic Style

Joe Wright’s Anna Karenina is as much an experiment in visual storytelling as it is a literary adaptation. The film’s theatrical conceit — conceived by production designer Sarah Greenwood — allows scenes to flow seamlessly from ballroom to bedroom to countryside, with backdrops sliding and walls dissolving like stage sets.

This constant motion mirrors the emotional turbulence of the characters and the fluidity of their moral boundaries. The lavish costumes, designed by Jacqueline Durran, blend historical accuracy with stylized elegance — the shimmering gowns and military uniforms reflecting the spectacle and constraint of high society.

Cinematographer Seamus McGarvey employs warm, painterly lighting for scenes of passion and icy blue tones for moments of repression. The contrast between the glittering interiors and the open landscapes of Levin’s world reinforces the film’s thematic duality — artifice versus authenticity, passion versus peace.

Dario Marianelli’s sweeping score, infused with Russian waltzes and melancholy strings, accentuates the rhythm of the film’s movement — from the fevered dances of love to the stillness of despair.

Symbolism

The film is rich in symbolic imagery. The train, appearing at key moments, represents both fate and destruction — the unstoppable force of desire and the inevitability of tragedy. The theatre stands for the social performance of aristocratic life, while mirrors symbolize self-awareness and vanity, reflecting Anna’s fractured identity.

Even costumes serve symbolic purpose: Anna’s black gowns in the latter half of the film foreshadow her psychological decline, while her early pastel dresses evoke innocence and vitality.

Conclusion

Anna Karenina (2012) is a cinematic masterpiece that transforms Tolstoy’s epic into an operatic meditation on love, morality, and the masks society forces us to wear. Joe Wright’s decision to stage the film as a living theatre transforms a 19th-century tragedy into a timeless reflection on performance, repression, and authenticity.

Keira Knightley’s mesmerizing performance captures the complexity of Anna’s character — a woman who dares to seek happiness in a world that forbids it. Jude Law’s compassionate Karenin and Domhnall Gleeson’s idealistic Levin add emotional depth and moral contrast.

Ultimately, the film reminds us that love, while beautiful, can also be ruinous when pursued without balance or understanding. Anna’s downfall is not simply the result of passion, but of a society that denies women the right to choose between duty and desire.

As the curtain falls on her tragedy, what remains is a haunting vision of beauty, sorrow, and truth — a reminder that behind every glittering façade lies the fragile, beating heart of humanity.