Ancient philosophy represents the earliest formal attempts by human beings to understand the world, the self, and the nature of existence through reason and argument. Spanning from roughly 600 BCE to 500 CE, it is the bedrock upon which Western and Eastern intellectual traditions were built. It encompasses a diverse range of thinkers and schools, from the pre-Socratics in Greece to the sages of India and China. This period laid the groundwork for virtually every major branch of philosophy: metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, and logic.

The Birth of Western Philosophy: Ancient Greece

The Pre-Socratics

The first known Western philosophers emerged in Ionia, a coastal region of Asia Minor, around the 6th century BCE. Known as the pre-Socratics, these thinkers turned from mythological explanations to rational inquiry about nature and existence.

- Thales of Miletus (c. 624–546 BCE) is often considered the first philosopher. He proposed that water is the fundamental substance (or arche) underlying all things, initiating the search for a unifying principle in nature.

- Anaximander introduced the concept of the apeiron—the boundless or infinite—as the source of all things.

- Heraclitus emphasized change as the fundamental nature of reality, famously stating that “you cannot step into the same river twice.” His notion of logos (reason or order) influenced later Stoic thought.

- Parmenides, by contrast, argued that change is an illusion and that true reality is unchanging and eternal. His emphasis on reason over the senses challenged thinkers for centuries.

These philosophers were primarily concerned with cosmology (the origin and structure of the universe), and although their theories may seem primitive today, their shift toward rational explanation marked a turning point in human thought.

Socrates (c. 470–399 BCE)

Socrates represents a decisive shift from cosmological concerns to ethical and epistemological inquiry. He left no writings of his own; his philosophy is known primarily through the dialogues of his student, Plato.

Socrates’ hallmark was the Socratic method, a dialectical approach involving asking probing questions to expose contradictions in one’s beliefs and arrive at deeper understanding. His guiding principle was that “the unexamined life is not worth living.” Socrates sought definitions for concepts like justice, courage, and virtue, believing that moral knowledge leads to right action.

His commitment to philosophical inquiry ultimately led to his trial and execution on charges of impiety and corrupting the youth. Yet his legacy endures as a symbol of intellectual integrity and the pursuit of truth.

Plato (c. 427–347 BCE)

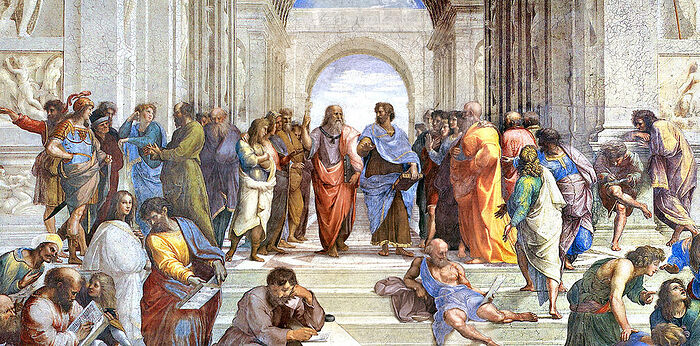

A student of Socrates and the founder of the Academy in Athens, Plato profoundly shaped Western thought. His writings, mostly dialogues, explore almost every area of philosophy.

Plato’s metaphysics is centered on the Theory of Forms: the belief that beyond the physical world lies a realm of perfect, unchanging Forms (or Ideas), of which objects in the material world are imperfect copies. For example, all beautiful things partake in the Form of Beauty.

In ethics and politics, Plato envisioned a just society governed by philosopher-kings, as outlined in his famous work, The Republic. He argued that justice is achieved when each class (rulers, auxiliaries, and producers) performs its proper role.

Plato’s influence is enduring, particularly his emphasis on reason and the search for eternal truths beyond sensory experience.

Aristotle (384–322 BCE)

A student of Plato and tutor to Alexander the Great, Aristotle took a more empirical and systematic approach than his teacher. He founded the Lyceum and wrote extensively on logic, ethics, politics, metaphysics, biology, and more.

Aristotle rejected Plato’s Theory of Forms, proposing instead that form exists within things themselves, not in a separate realm. He introduced the concept of substance and developed a system of logic (syllogistic logic) that remained dominant until the 19th century.

In ethics, Aristotle emphasized the concept of eudaimonia (flourishing or well-being), achieved by living a life of virtue in accordance with reason. His doctrine of the Golden Mean advocated moderation between extremes (e.g., courage as a mean between recklessness and cowardice).

Aristotle’s political philosophy, detailed in Politics, classified governments and emphasized the importance of the polis (city-state) as a natural and essential part of human life.

Hellenistic Philosophy

Following the conquests of Alexander the Great, Greek culture spread across the Mediterranean and Near East, giving rise to new philosophical schools that addressed how individuals should live in a rapidly changing and often chaotic world.

The Stoics

Founded by Zeno of Citium (c. 334–262 BCE), Stoicism taught that the path to happiness lies in living in accordance with nature and reason. The Stoics emphasized self-control, rationality, and acceptance of fate. They believed that external events are beyond our control, but we can control our responses.

Famous Stoics include Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius. Their writings continue to inspire those seeking resilience and inner peace.

Epicureanism

Epicurus (341–270 BCE) founded a school that taught that pleasure, understood as the absence of pain (ataraxia), is the highest good. However, he emphasized intellectual pleasures and friendship over indulgent hedonism. Epicureans also believed in atomism—the idea that all things are composed of atoms and void—drawing from Democritus.

Skepticism and Cynicism

- Pyrrho of Elis (c. 360–270 BCE) founded Skepticism, which argued that certainty is impossible and that suspending judgment (epoché) leads to tranquility.

- Diogenes of Sinope, a founder of Cynicism, advocated a life in accordance with nature and rejected social conventions and material possessions. He famously lived in a barrel and mocked the pretensions of society.

Roman Philosophy

Roman thinkers adopted and adapted Greek philosophy, often integrating it into the Roman ethical and political framework.

- Cicero (106–43 BCE) popularized Stoicism and Platonism for Roman audiences.

- Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius developed Stoic thought into a practical philosophy of life.

- Lucretius (c. 99–55 BCE), in his poem On the Nature of Things, articulated Epicurean philosophy and a naturalistic view of the universe.

Ancient Indian Philosophy

Parallel to Greek developments, India produced a rich and systematic philosophical tradition, often tied to religious thought.

- The Vedas (c. 1500 BCE) and Upanishads (c. 800–200 BCE) contain the earliest philosophical reflections, emphasizing concepts like Brahman (ultimate reality) and Atman (self).

- Buddhism, founded by Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha), rejected caste and ritualism, teaching the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path as a means to liberate oneself from suffering.

- Jainism, with figures like Mahavira, advocated nonviolence (ahimsa), asceticism, and the relativity of truth (anekantavada).

- The Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, and Vedanta schools developed sophisticated metaphysical and epistemological theories, rivaling their Western counterparts in depth and complexity.

Ancient Chinese Philosophy

Chinese philosophy, centered on ethics and social harmony, developed independently of the West and India.

- Confucius (551–479 BCE) emphasized moral virtue, familial piety (filial respect), and social roles. His teachings formed the basis of Confucianism.

- Laozi, attributed author of the Tao Te Ching, founded Daoism (Taoism), which emphasized living in harmony with the Dao (Way), spontaneity, and naturalness.

- Legalism, advocated by Han Feizi, promoted strict laws and centralized authority to maintain order.

- Mohism, founded by Mozi, emphasized universal love and meritocratic governance.

Legacy of Ancient Philosophy

Ancient philosophy, East and West, provided the vocabulary, methods, and conceptual frameworks that shaped civilizations. In the West, the legacy of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle dominated medieval scholasticism and inspired the Renaissance and Enlightenment. In the East, Confucian and Daoist principles influenced governance, culture, and personal conduct for millennia.

Even today, ancient philosophical teachings remain deeply relevant. Whether it’s the Stoic approach to emotional resilience, the Buddhist path to mindfulness, or the Socratic demand for self-examination, these ancient voices continue to guide and challenge us.