Introduction

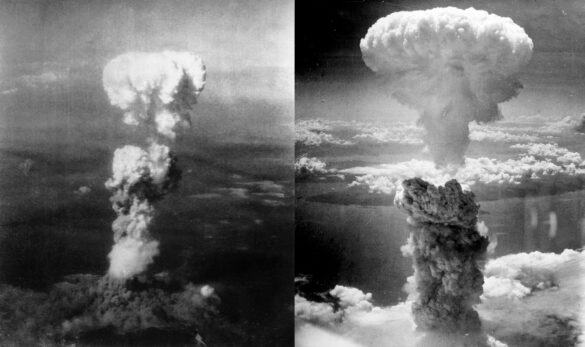

In August 1945, two atomic bombs were dropped by the United States on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, marking the first and only time nuclear weapons have been used in warfare. These bombings not only brought an abrupt end to World War II, but also ushered in a new era—one defined by nuclear weapons, Cold War tensions, and global anxieties over the terrifying power of science turned toward destruction.

The events of August 6 and 9, 1945, were a turning point in human history. They were the culmination of years of scientific research, military strategy, political calculation, and ethical debate. The bombings resulted in the deaths of over 200,000 people, most of them civilians, and left deep scars—physical, psychological, and moral—that endure to this day.

The Road to the Bomb: The Manhattan Project

The atomic bomb was the product of the Manhattan Project, a top-secret U.S. research and development effort during World War II. Initiated in 1939 and formally organized in 1942, the project involved some of the greatest scientific minds of the time, including J. Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, Niels Bohr, and others. The fear that Nazi Germany was also working on nuclear weapons accelerated the urgency of the project.

With sites in Los Alamos (New Mexico), Oak Ridge (Tennessee), and Hanford (Washington), the Manhattan Project eventually employed over 130,000 people and cost nearly $2 billion USD at the time (equivalent to tens of billions today). Its scientific breakthrough came with the successful test of the first atomic bomb, code-named Trinity, on July 16, 1945, in the New Mexico desert. The sheer force of the explosion stunned even the scientists who created it.

Context: The End of World War II in Sight

By the summer of 1945, Nazi Germany had already surrendered in May. However, the Pacific War continued as Japan refused to unconditionally surrender. Fierce battles such as Iwo Jima and Okinawa demonstrated the ferocity with which Japanese forces would fight, often to the death, and raised concerns about the massive loss of life a full-scale invasion of the Japanese mainland would cause—some estimates ran as high as 1 million Allied casualties.

At the Potsdam Conference (July 17–August 2, 1945), the Allied leaders—Harry S. Truman, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin—issued the Potsdam Declaration, calling for Japan’s unconditional surrender. Japan rejected the ultimatum.

President Truman, now fully informed of the bomb’s capabilities, made the controversial decision to use the new weapon to force Japan’s hand and, arguably, to also demonstrate U.S. power to the Soviet Union.

Hiroshima: August 6, 1945

At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, the U.S. B-29 bomber Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets, dropped the atomic bomb code-named “Little Boy” over the city of Hiroshima. The bomb, which used uranium-235, exploded with a force equivalent to 15,000 tons of TNT.

Within seconds, a fireball several million degrees Celsius incinerated everything within a radius of about one mile. A blast wave flattened buildings, and a radiation surge spread outward. An estimated 70,000–80,000 people were killed instantly, with tens of thousands more dying from burns, radiation sickness, and injuries in the following weeks and months.

The city was virtually annihilated. Hospitals were destroyed, doctors killed, and survivors—many of them severely burned—were left with little aid. Eyewitnesses described haunting scenes of people with charred skin hanging from their limbs, wandering through a hellscape of fire, smoke, and ash.

Nagasaki: August 9, 1945

Three days later, on August 9, 1945, the U.S. dropped a second atomic bomb—this one code-named “Fat Man”—on the city of Nagasaki. Originally, the target had been Kokura, but cloud cover and visibility issues caused the pilot to divert to the secondary target.

The Nagasaki bomb used plutonium-239 and exploded with a force of approximately 21,000 tons of TNT. The geography of Nagasaki’s valleys and hills slightly limited the destruction compared to Hiroshima, but the bomb still caused immense devastation.

Around 40,000 people died instantly, with the total death toll reaching over 70,000 by the end of 1945 due to injuries and radiation-related illnesses. Buildings, homes, and infrastructure were flattened; thousands of survivors suffered lifelong disabilities and trauma.

Japan’s Surrender

Following the second bombing and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan on August 8, Emperor Hirohito intervened and declared his intention to surrender. On August 15, 1945, Japan announced its surrender via radio broadcast—an unprecedented act, as the Emperor had never before addressed the nation directly.

On September 2, 1945, Japanese officials signed the Instrument of Surrender aboard the U.S. battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay, officially ending World War II.

Immediate Aftermath and Human Toll

The human cost of the bombings was staggering:

- Total deaths by the end of 1945 from both cities are estimated at 200,000+, mostly civilians.

- Many survivors, known as hibakusha, suffered lifelong physical and psychological trauma.

- Cancer rates and birth defects increased sharply among survivors.

- Social stigma in Japan made it difficult for hibakusha to marry or find employment.

- Cities were rebuilt slowly, and monuments now stand in remembrance of the victims.

Ethical and Political Controversy

The atomic bombings have long been the subject of intense moral, historical, and political debate:

- Justification: Supporters argue the bombings were necessary to end the war swiftly and save more lives than a land invasion would have cost.

- Criticism: Opponents believe Japan was already on the brink of surrender, and the bombings were excessive, targeting civilians and introducing nuclear warfare into the world.

Some historians suggest that the bombings were also a geopolitical message to the Soviet Union, signaling the emergence of U.S. dominance in the post-war world. This interpretation suggests that Cold War dynamics were already influencing strategic decisions.

Legacy and Lessons

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki forever changed the trajectory of human history. They:

- Marked the beginning of the nuclear age.

- Prompted a global arms race during the Cold War.

- Sparked movements for nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation.

- Led to the creation of treaties such as the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and organizations like the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

In Japan, both cities have become symbols of peace and advocates for a world free of nuclear weapons. Hiroshima holds an annual Peace Memorial Ceremony, and the Peace Memorial Park and Atomic Bomb Dome are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Conclusion

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were acts of unimaginable devastation that reshaped the modern world. While they effectively ended World War II, they also opened a terrifying chapter in human capability for destruction. The ethical dilemmas, the suffering of survivors, and the shadow of nuclear warfare continue to provoke debate and reflection today.

These events remind humanity of the fine line between scientific progress and catastrophic misuse, and they challenge future generations to seek peace, diplomacy, and understanding in an increasingly complex world.