The transatlantic slave trade was one of the darkest chapters in human history, spanning over four centuries and involving the forced enslavement of millions of Africans. Enslaved individuals were shipped across the Atlantic Ocean under appalling conditions and sold into brutal labor in the Americas. The abolition of this trade was not merely a legislative act but the result of decades of resistance, advocacy, economic change, and moral awakening. It marked a critical shift in global consciousness and laid the groundwork for the broader abolition of slavery itself.

Origins of the Slave Trade

The slave trade began in the 15th century with Portuguese exploration along the African coast. Over time, other European powers — including Britain, Spain, France, the Netherlands, and Denmark — became heavily involved. The transatlantic slave trade formed a part of the so-called “triangular trade”: European goods were traded for enslaved Africans, who were then transported to the Americas to work on plantations, particularly growing sugar, cotton, coffee, and tobacco. The goods produced by slave labor were shipped back to Europe, creating a cycle of exploitation and profit.

At its peak in the 18th century, the trade saw the forced transportation of approximately 12 million Africans, though some estimates place the total number even higher. Mortality rates on the Middle Passage — the harrowing journey across the Atlantic — were high due to overcrowding, disease, malnutrition, and abuse. Entire families were destroyed, societies disrupted, and generations lost to bondage.

Moral Awakening and Early Opposition

Despite the widespread acceptance of slavery by governments and elites, there were early voices of dissent. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Quakers (the Religious Society of Friends) emerged as some of the first organized opponents of slavery. Their religious conviction that all human beings were equal in the eyes of God made the practice of slavery fundamentally abhorrent.

In Britain, a powerful anti-slavery movement began to gather momentum in the late 18th century. Among the most influential figures was Thomas Clarkson, who dedicated his life to collecting evidence about the brutal realities of the slave trade. His tireless efforts included interviews with former enslaved people, sea captains, and ship doctors.

The most famous abolitionist in British history, William Wilberforce, took up the cause in Parliament. A devout Christian and a Member of Parliament, Wilberforce became the face of legislative campaigns against the trade, introducing bills and mobilizing public support.

Public Campaigns and Advocacy

The abolitionist movement used innovative methods to change public opinion. Campaigners organized petitions, boycotts of slave-produced sugar, and public lectures. One of the most iconic symbols of the movement was a medallion crafted by Josiah Wedgwood with the image of a kneeling enslaved man and the words: “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?”

Print culture played a vital role. Autobiographical narratives, such as Olaudah Equiano’s The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, gave a voice to the formerly enslaved and provided firsthand accounts of the cruelty of the slave trade. These works humanized the enslaved in a way that statistics and general descriptions could not.

Women, though often excluded from formal politics, played a vital role in grassroots campaigns. They organized societies, hosted meetings, and influenced household consumption, thereby helping to create an anti-slavery culture at home.

Legislative Victory: The 1807 Act

After years of persistent effort, the British Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act in 1807, which made it illegal to engage in the slave trade throughout the British Empire. This was a monumental victory for the abolitionist movement, though it did not abolish slavery itself — only the trade in enslaved persons.

The 1807 Act allowed the Royal Navy to intercept slave ships and free those on board. The West Africa Squadron, a naval unit established by Britain, patrolled the Atlantic and captured hundreds of slave ships, liberating thousands of Africans. However, enforcement was difficult, and illegal trading continued under false flags and bribery.

International Abolition

Britain’s decision in 1807 had international implications. British diplomats began pressuring other nations to end their involvement in the trade. Treaties were signed with countries like Portugal, Spain, and Brazil to limit or end their slave trading activities. The United States also passed legislation in 1808, banning the importation of enslaved persons.

However, some countries continued the trade for decades. Brazil and Cuba, in particular, remained major players in the illegal slave trade well into the mid-19th century. It was not until 1867 that Brazil officially outlawed the slave trade, although slavery itself would continue there until 1888.

Abolition of Slavery vs. the Slave Trade

It is crucial to distinguish between the abolition of the slave trade and the abolition of slavery itself. While the former dealt with the capture, sale, and transport of enslaved Africans, the latter addressed the institution of slavery and the condition of those already enslaved.

In Britain, slavery within its colonies continued after 1807. It was only with the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 that slavery was officially abolished in most of the British Empire. Even then, enslaved people were subjected to a so-called “apprenticeship” period, a thinly veiled continuation of forced labor, until full emancipation came in 1838.

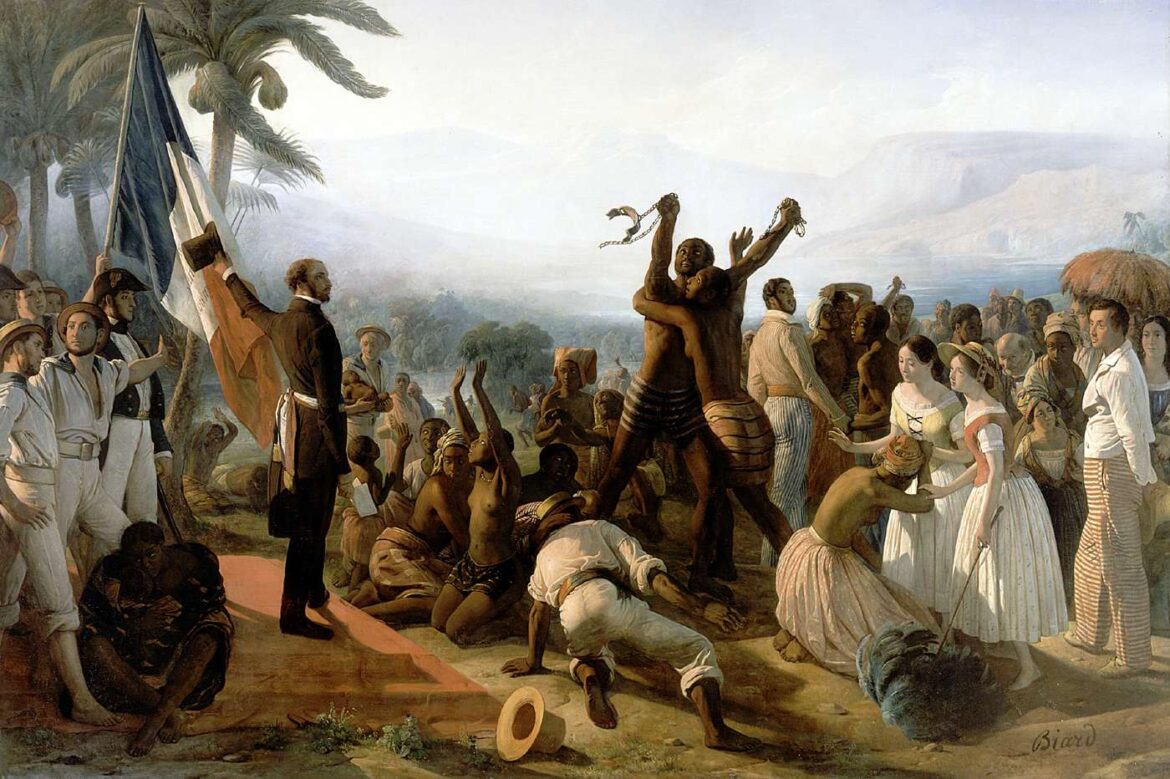

In the United States, slavery was abolished with the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1865, following the end of the Civil War. In France, slavery was abolished in 1794, reinstated by Napoleon in 1802, and finally abolished again in 1848. Brazil, the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery, did so in 1888.

The Role of African Resistance

Often overlooked in Western narratives is the active resistance of African people themselves. Africans resisted capture, revolted aboard slave ships, and led rebellions in the colonies. One of the most famous examples is the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), in which enslaved people in the French colony of Saint-Domingue rose up and eventually defeated the French, establishing the first Black republic and abolishing slavery.

This revolution sent shockwaves throughout the colonial world and demonstrated that enslaved people were not passive victims but agents of their own liberation.

Economic and Political Factors

While moral and humanitarian arguments were crucial, economic and political changes also influenced the abolition of the slave trade. The Industrial Revolution shifted the British economy away from reliance on slave-produced commodities. Factory owners preferred a free labor market where workers could be hired and dismissed, rather than a plantation economy based on bondage.

Moreover, slave rebellions and resistance increased the cost of maintaining slavery. The constant threat of insurrection and the need for military intervention made the system increasingly untenable.

Geopolitical interests also played a part. By outlawing the trade and pushing others to do the same, Britain sought to undermine its colonial rivals, especially Spain and Portugal, who still profited from the trade.

Legacy and Continuing Impact

The abolition of the slave trade was a watershed moment, but it did not erase the deep scars left by centuries of exploitation. The effects of slavery are still evident today in persistent racial inequalities, economic disparities, and social injustices across the globe.

In recent years, there has been a growing movement to re-examine history, remove statues of slave traders, and demand reparations for descendants of the enslaved. Museums, governments, and educational institutions have begun to confront their roles in perpetuating or profiting from slavery.

Understanding the history of the abolition movement is crucial not just for recognizing a moral triumph, but also for appreciating the enduring consequences of slavery and the ongoing struggle for racial justice.

Conclusion

The abolition of the slave trade was a long and complex process driven by a combination of moral, social, political, and economic forces. It was shaped by the bravery of enslaved people who resisted oppression, the commitment of abolitionists who challenged the status quo, and the gradual realization by global powers that such a system was incompatible with modern ideals of freedom and justice.

Though the trade has been abolished for more than two centuries, its echoes continue to resonate in contemporary society. Remembering this history is essential—not only to honor those who suffered and resisted but also to ensure that such atrocities are never repeated.