The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century stands as one of the most transformative innovations in human history. It revolutionized the way knowledge was disseminated, reshaped societies, and laid the foundation for the modern information age. Before Gutenberg’s press, the production of books and written materials was a laborious, expensive process, limited to monasteries, scribes, and the elite. With the printing press, mass communication became possible, paving the way for major cultural, religious, and intellectual shifts, including the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution.

Historical Context: Europe Before the Printing Press

Before the advent of the printing press, books were produced by hand-copying texts onto parchment or vellum, a slow and costly method that meant books were rare and typically only available in monasteries, universities, or the libraries of the wealthy. Literacy rates were low, and most people relied on oral traditions or public readings for information. The control of knowledge and education rested largely in the hands of the Church, which preserved and transmitted religious texts.

The rise of towns, trade, universities, and the spread of humanism in the 14th and 15th centuries created a growing demand for books. However, the traditional manuscript-copying method could not meet this increasing appetite for learning. Innovations in paper production and ink formulation had already laid some groundwork for change, but a breakthrough was needed in the realm of text reproduction.

The Life of Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gutenberg was born around 1400 in Mainz, Germany. He came from a wealthy merchant family and was well-educated, trained in metalworking, and skilled in engraving. His background in metallurgy, combined with his exposure to various mechanical technologies, provided the technical knowledge and experience he would later apply to his printing press.

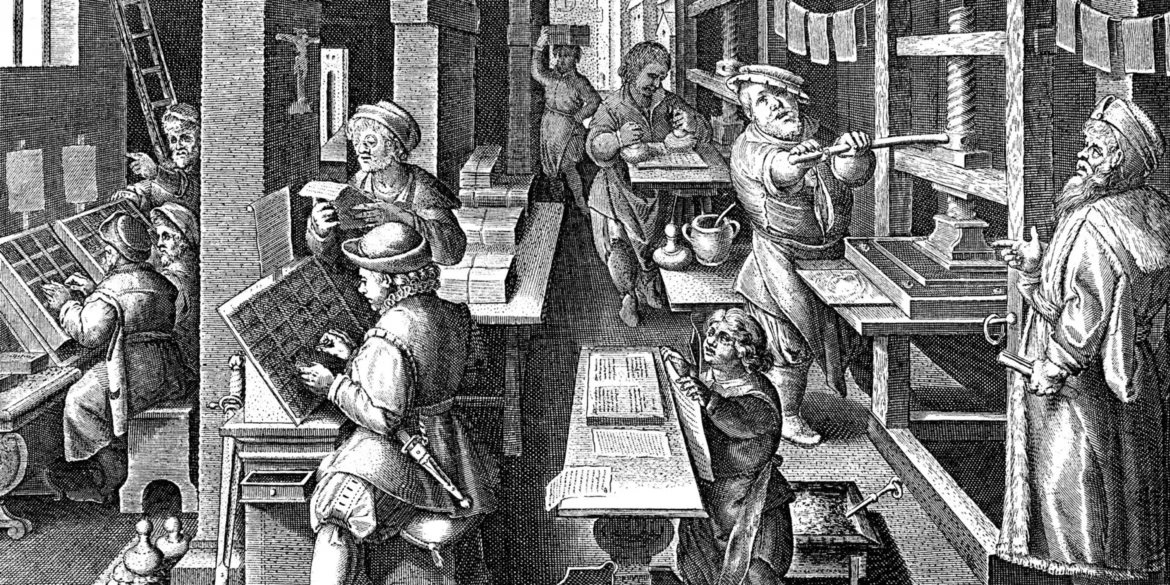

Gutenberg’s genius lay not only in his technical skill but also in his ability to synthesize existing technologies into a coherent and effective system. He combined movable type, oil-based ink, and a modified wine press to create a mechanized printing system capable of producing texts quickly, cheaply, and in large quantities.

The Invention of the Printing Press

Gutenberg’s most significant innovation was the development of movable metal type. While movable type had been used earlier in China and Korea using wood and ceramic, Gutenberg’s metal type was more durable and precise. He cast individual letters (type) from a lead-based alloy that was both hard enough to withstand repeated use and soft enough to be cast in molds. This allowed for the mass production of type and the consistent reproduction of text.

Gutenberg also developed a special oil-based ink that adhered well to the metal type and the paper. He adapted a screw press—commonly used in wine and olive oil production—for use in printing. This press enabled even pressure to be applied to paper laid on the inked type, resulting in clear, uniform impressions.

Together, these innovations formed a cohesive system that could produce hundreds of pages in the time it would take a scribe to write a few. Around 1450, Gutenberg began printing, and by 1455, he had completed his most famous work: the Gutenberg Bible.

The Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible, also known as the 42-line Bible, was the first major book printed using movable type in the West. It is widely regarded as a masterpiece of design and craftsmanship. Gutenberg printed approximately 180 copies, of which about 49 survive today in various conditions.

The Bibles were printed in Latin, in a format that closely resembled handwritten manuscripts to make them more acceptable to traditionalists. Many copies were hand-illuminated by artists after printing, blending the old and the new. The success of the Gutenberg Bible demonstrated that the printing press could meet the high standards of medieval book production and helped gain acceptance for the new technology.

Economic and Social Impact

The economic implications of Gutenberg’s press were profound. The cost of producing books dropped dramatically, making books more affordable and accessible to a broader segment of the population. This accessibility led to a rapid increase in literacy rates across Europe.

Book production skyrocketed. By 1500, only 50 years after Gutenberg’s Bible, it is estimated that over 20 million books had been printed. By 1600, the number had grown to over 200 million. This explosion of printed material facilitated the spread of knowledge, ideas, and information at an unprecedented scale.

The printing press also stimulated new industries and trades, such as paper-making, bookbinding, and the selling of books and pamphlets. Printing centers sprang up across Europe, in cities such as Venice, Paris, and Nuremberg. The press also gave rise to the first publishers and authors who could now reach a mass audience.

Intellectual and Cultural Revolution

The most profound impact of the printing press was intellectual. The press broke the monopoly of the Church and aristocracy on education and information. The spread of books contributed to the Renaissance, as classical texts and new humanist ideas circulated widely. Scholars could now access and debate ideas more freely and build upon each other’s work.

The press also played a critical role in the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, nailed to a church door in 1517, would likely have remained a local protest without the printing press. Instead, they were reproduced and spread across Europe, igniting a movement that challenged the authority of the Catholic Church and led to the creation of Protestant denominations.

Scientific knowledge also flourished. The printing press enabled the rapid dissemination of scientific discoveries and ideas, fostering collaboration across national and disciplinary lines. The Scientific Revolution owed much to the printed word, which made it possible to verify, replicate, and challenge scientific claims.

Challenges and Controversies

Despite its revolutionary nature, the printing press was not without its critics. Authorities, particularly religious institutions, feared the spread of heretical or subversive ideas. In response, censorship and licensing systems were developed to control what could be printed.

There were also concerns about information overload. As more texts became available, some thinkers worried that people would be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of material, unable to discern quality from falsehood—a concern that echoes today in the digital age.

Legacy and Modern Parallels

The printing press is often likened to the internet in terms of its impact on society. Both enabled the mass dissemination of information and transformed how people learn, communicate, and interact with the world. Gutenberg’s press laid the groundwork for the modern knowledge-based society and democratized learning.

Today, the printing press is seen as a turning point in history, marking the end of the medieval era and the beginning of the modern age. It is one of the key developments that enabled the Enlightenment, the rise of modern democracies, and the global expansion of education and literacy.

Conclusion

Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press was not merely a technological achievement—it was a catalyst for profound cultural and societal change. By making books more accessible, it opened the door to mass literacy, education, and the free exchange of ideas. It undermined the monopolies of religious and political elites over knowledge and empowered individuals to think, learn, and challenge.

The ripple effects of Gutenberg’s press continue to this day. Every time we open a book, read a newspaper, or browse an online article, we are beneficiaries of the printing revolution that began over 500 years ago in Mainz, Germany. Gutenberg’s legacy is that of a true visionary whose invention helped shape the modern world.