Introduction

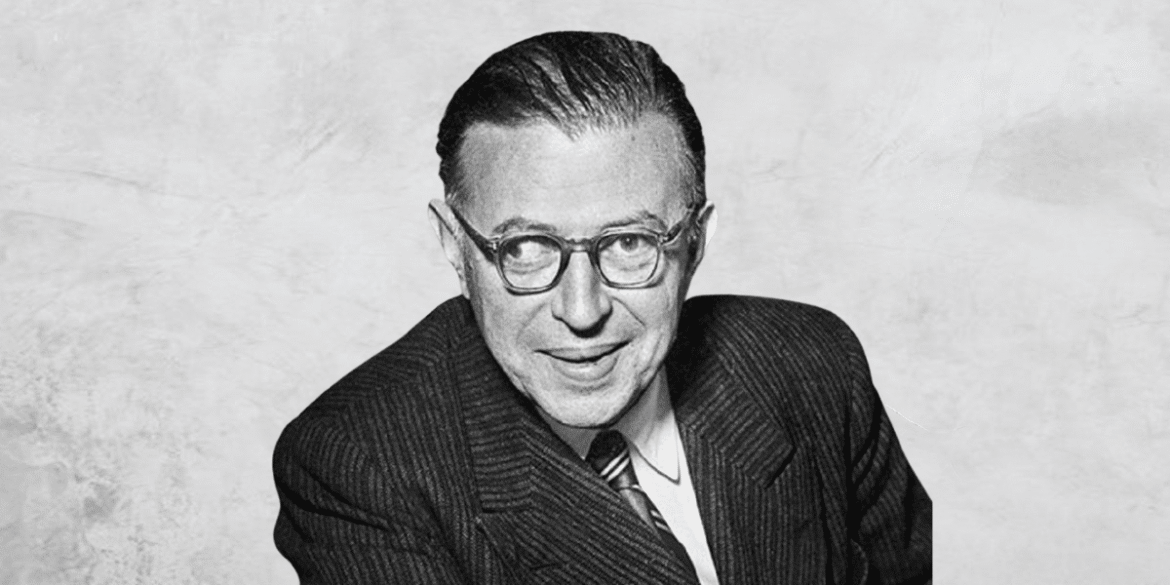

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, political activist, and literary critic, best known as the leading figure of existentialism and one of the most influential intellectuals of the 20th century. Sartre’s philosophy centered on human freedom, individual responsibility, and the absurdity of existence. His works—spanning dense philosophical treatises to gripping plays and novels—convey the message that humans are condemned to be free, and must shape their own lives without relying on divine or predetermined meaning.

Sartre’s contributions to philosophy, literature, and political thought marked a turning point in modern humanism. He brought philosophy out of the academic halls and into the streets, engaging with social issues, Marxism, war, colonialism, and personal authenticity.

Early Life and Education

Jean-Paul Sartre was born on June 21, 1905, in Paris. His father died when he was an infant, and he was raised by his mother and maternal grandfather, Charles Schweitzer. A precocious and curious child, Sartre was deeply influenced by literature and philosophy from an early age. He studied at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure, where he met lifelong companion Simone de Beauvoir and was exposed to the works of philosophers such as Hegel, Kant, and Husserl.

Sartre later studied phenomenology in Germany under Edmund Husserl and was deeply influenced by Martin Heidegger, whose work Being and Time helped shape Sartre’s existential outlook. Sartre’s interest in phenomenology—the study of consciousness and experience—would serve as the foundation for his own philosophical explorations.

Existentialism: Freedom and Responsibility

Sartre’s version of existentialism can be summarized by his famous dictum: “Existence precedes essence.” This means that humans are not born with a predefined purpose or nature (essence); instead, they come into existence first and then create their essence through actions and choices.

In his magnum opus, Being and Nothingness (1943), Sartre explores key existential concepts:

- Being-for-itself (être-pour-soi): The conscious human being who defines themselves through freedom.

- Being-in-itself (être-en-soi): The inanimate objects of the world that simply exist without consciousness.

- Nothingness (néant): The capacity of consciousness to negate, to separate itself from what is and imagine what is not.

Humans, according to Sartre, are condemned to be free. There is no God or higher authority to dictate our actions, and thus we bear the full weight of responsibility for our choices. This absolute freedom can be a source of anxiety—what Sartre calls anguish—but it is also the condition of human dignity.

Sartre believed that most people fall into bad faith (mauvaise foi), a form of self-deception in which they deny their own freedom and responsibility by adopting social roles or external identities. For example, a waiter who convinces himself that he is nothing more than a waiter is in bad faith, because he is more than that role—he is a free consciousness capable of choosing something else.

Literary Contributions

Sartre’s existential philosophy is not confined to abstract treatises. He also conveyed his ideas through novels, short stories, and plays that dramatize existential themes.

Nausea (1938)

This novel, often regarded as the first major work of existentialist literature, tells the story of Antoine Roquentin, a man who becomes acutely aware of the absurdity and contingency of existence. He experiences profound existential vertigo—nausea—as he realizes the sheer fact that things exist without reason. The novel exemplifies Sartre’s belief that reality has no inherent meaning and that meaning must be created.

No Exit (1944)

This one-act play introduces the famous line “Hell is other people.” It portrays three characters trapped in a room for eternity, forced to confront their past actions and the way they are perceived by others. The play explores the tension between self-identity and how one is viewed by others, as well as themes of guilt, bad faith, and inescapable freedom.

The Roads to Freedom Trilogy

This unfinished series of novels (The Age of Reason, The Reprieve, Troubled Sleep) traces the lives of several characters before and during World War II, examining how they respond to political crisis, war, and the burden of freedom. It is a literary extension of his existential ideas set against the backdrop of real historical events.

Political Engagement and Marxism

Sartre believed that philosophy should be practical and engaged with the real world. After World War II, he became increasingly involved in political causes, aligning himself with Marxism though never fully joining the Communist Party.

Sartre saw Marxism as a necessary framework for understanding historical and economic structures, but he also criticized its determinism. In Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960), he attempted to reconcile existentialism with Marxism, arguing for a synthesis of individual agency and structural analysis.

He was a vocal critic of colonialism, supporting Algerian independence and opposing French imperialism. During the Vietnam War, he condemned American intervention and served as a symbolic president of the Russell Tribunal, which investigated American war crimes.

Throughout the Cold War, Sartre maintained a controversial position, defending Soviet policies at times but also criticizing Stalinism and authoritarianism. His political activism led to tensions with other intellectuals, but it also secured his place as a figure deeply committed to justice and human dignity.

Relationship with Simone de Beauvoir

Sartre’s life and philosophy were closely intertwined with Simone de Beauvoir, a fellow philosopher and feminist. Though they never married or lived together, they maintained a lifelong intellectual and romantic partnership.

De Beauvoir’s work The Second Sex (1949) was heavily influenced by Sartre’s existentialism, but also expanded it to include gender and the condition of women. Their collaboration demonstrated the potential for existential thought to address concrete social inequalities.

Both Sartre and de Beauvoir lived out their philosophy, embracing freedom, authenticity, and unconventional relationships. Their partnership remains one of the most famous intellectual alliances of the 20th century.

Sartre and the Nobel Prize

In 1964, Jean-Paul Sartre was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, but he refused it. He believed that a writer should not become an institution and that accepting the prize would compromise his independence. Sartre had long rejected formal honors and awards, consistent with his existential belief in individual authenticity.

Legacy and Influence

Jean-Paul Sartre left a vast intellectual legacy that continues to resonate:

- Philosophy: He helped popularize existentialism, influencing thinkers in existential psychology, theology, ethics, and political theory.

- Literature: His novels and plays are considered classics of 20th-century literature and remain widely read.

- Politics: He helped shape postwar political discourse, especially in France, inspiring generations of activists, students, and public intellectuals.

- Existentialism in Culture: Sartre’s ideas permeated existentialist art, cinema, and culture, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, influencing works like Albert Camus’s The Stranger and later postmodern thinkers.

Despite criticism that his work can be abstract, overly bleak, or politically naïve, Sartre’s unwavering commitment to human freedom and moral responsibility makes his thought enduringly relevant.

Conclusion

Jean-Paul Sartre was a philosopher of radical freedom. He challenged humanity to face a universe devoid of inherent meaning and to courageously create values through action, choice, and authenticity. His existentialism urged individuals to reject excuses and live with integrity, even in a world marked by absurdity, anxiety, and injustice.

Sartre not only theorized about human existence—he lived his philosophy. Through his writing, teaching, and activism, he exemplified the engaged intellectual who saw no divide between thought and action. His legacy continues to inspire those who seek to understand what it means to be human in a free but uncertain world.