Twice each year, the Earth performs a subtle yet profound movement that marks the turning point of the seasons: the solstice. Derived from the Latin words sol (sun) and sistere (to stand still), the solstice represents the moment the sun appears to pause in its journey across the sky before reversing direction. This celestial event has been observed and revered by cultures around the world for thousands of years, signifying more than just the change of seasons — it marks a time of reflection, renewal, celebration, and awe.

What Is the Solstice?

Astronomically, a solstice occurs when the Earth’s axial tilt is at its maximum inclination toward or away from the Sun. There are two solstices each year:

- The Summer Solstice, occurring around June 20–21 in the Northern Hemisphere and December 21–22 in the Southern Hemisphere.

- The Winter Solstice, occurring around December 21–22 in the Northern Hemisphere and June 20–21 in the Southern Hemisphere.

During the Summer Solstice, the hemisphere tilted toward the Sun experiences the longest day and shortest night of the year. Conversely, during the Winter Solstice, that same hemisphere experiences the shortest day and longest night.

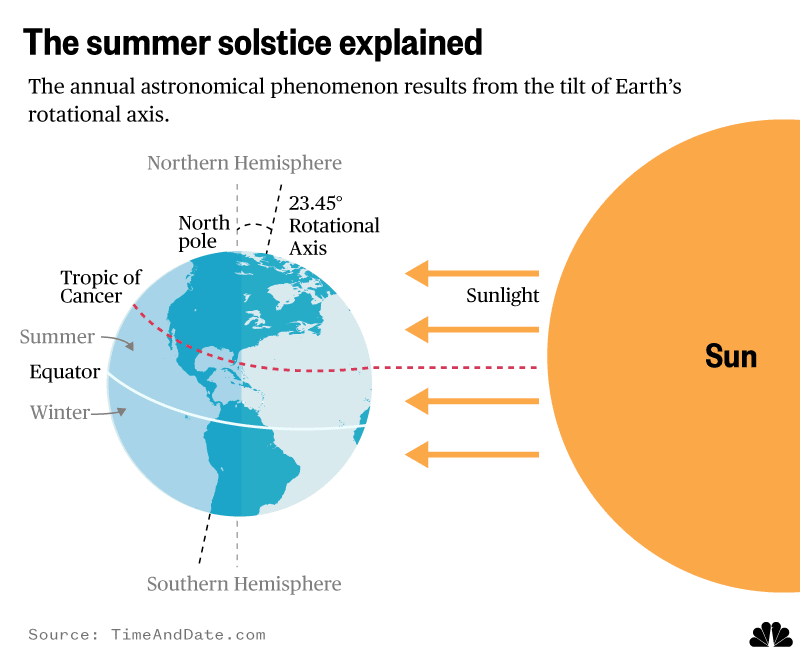

These solstices mark the extremes of daylight variation and are a direct result of Earth’s 23.5° axial tilt. Without this tilt, we would have no seasons — and thus, no solstices.

The Solstice in Ancient Civilizations

Long before telescopes and scientific explanations, ancient people tracked the solstices using natural landmarks, stone structures, and religious rituals. These events often held significant spiritual and agricultural meanings.

Stonehenge (England)

Perhaps the most famous solstice-aligned monument is Stonehenge, the prehistoric stone circle in Wiltshire, England. Archaeological evidence suggests that the site was carefully designed to align with the movements of the sun. On the Summer Solstice, the sun rises directly over the Heel Stone when viewed from the center of the circle, drawing thousands of visitors each year to celebrate the event.

Newgrange (Ireland)

In Ireland, the Newgrange passage tomb, built over 5,000 years ago, is aligned with the Winter Solstice. Each year, around December 21st, the rising sun shines through a small opening above the entrance and illuminates the interior chamber for about 17 minutes — a feat of ancient engineering that emphasizes the significance of light’s return during the darkest part of the year.

Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians aligned several temples with the sun, and the Summer Solstice was particularly important. The rising of the Nile River — crucial for agriculture — was closely tied to the Summer Solstice and the heliacal rising of the star Sirius. This event also marked the beginning of the Egyptian New Year.

Mayan and Aztec Civilizations

Mesoamerican cultures such as the Maya and Aztecs constructed pyramids and observatories that marked solstices and equinoxes. For example, the El Castillo pyramid at Chichén Itzá casts a shadow that creates the illusion of a serpent descending the steps during the solstices and equinoxes — a dramatic spectacle with spiritual and astronomical importance.

Solstice Festivals and Traditions

Solstices are celebrated in various forms around the globe, both ancient and modern. Many cultures have rituals, festivals, or holidays tied to these events.

Midsummer (Scandinavia)

In Northern Europe, particularly Sweden, Finland, and Norway, the Summer Solstice is celebrated as Midsummer. People gather around bonfires or decorate maypoles with flowers and greenery. It’s a time of joy, light, fertility, and sometimes mischief, rooted in ancient pagan customs.

Inti Raymi (Inca Festival of the Sun)

In Peru, the Inca civilization honored Inti, the sun god, during the Winter Solstice of the Southern Hemisphere. The Inti Raymi festival, still celebrated today in Cusco, involves parades, dancing, colorful costumes, and a reenactment of ancient ceremonies.

Dongzhi Festival (China)

The Dongzhi Festival in China marks the Winter Solstice and dates back thousands of years. It celebrates the increase of positive energy (yang) as the days begin to lengthen. Families traditionally gather to eat tangyuan (glutinous rice balls) symbolizing unity and prosperity.

Yule (Pagan Europe)

The Winter Solstice also coincides with Yule, an ancient Germanic and Norse festival that honored the rebirth of the sun. Many of our modern Christmas traditions — such as decorating trees, lighting candles, and the burning of the Yule log — have roots in these pagan solstice celebrations.

Solstices and Spiritual Symbolism

Beyond astronomy and cultural festivities, the solstices hold deep spiritual significance. They represent the eternal cycle of light and darkness, life and death, growth and rest. Many spiritual traditions view the solstices as opportunities for inner transformation.

The Summer Solstice

Symbolically, the Summer Solstice is a celebration of abundance, light, and growth. The sun, at its peak, represents clarity, enlightenment, and creative energy. Spiritually, it’s a time to manifest intentions, express gratitude, and embrace the fullness of life.

Some view it as a metaphorical “zenith” of the human soul — a period when we shine our brightest. Yet, as the day begins to shorten after the solstice, it also teaches us that even peak moments are transient. This duality brings about reflection and a grounding sense of humility.

The Winter Solstice

The Winter Solstice, conversely, is a time of introspection, stillness, and renewal. It marks the rebirth of the sun, and with it, the hope of new beginnings. It symbolizes emerging from darkness — literally and metaphorically.

Spiritual practices during this time often involve quiet meditation, candlelight ceremonies, and personal reflection. Many people set intentions for the coming year, much like the resolutions made around New Year’s Day. It’s a time to release the old and welcome the new.

Scientific Impact and Relevance

Though steeped in myth and culture, solstices are fundamentally scientific events with real-world implications. For example:

- Climate and Agriculture: Solstices mark key points in seasonal cycles, influencing agriculture, planting, and harvesting schedules.

- Biological Rhythms: Many animals and plants use the amount of daylight to regulate behavior like hibernation, migration, and reproduction.

- Modern Calendars: Our modern calendar systems are heavily influenced by solar events, including solstices and equinoxes, to keep time and organize society.

In some regions, energy usage patterns and human behavior are also influenced by daylight duration. The psychological effects of light — especially relevant around the Winter Solstice when Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is more prevalent — remind us that celestial movements still impact our daily lives.

Conclusion

The solstice is far more than an astronomical anomaly or an ancient relic of human superstition. It is a timeless phenomenon that continues to connect us — physically, culturally, and spiritually — to the rhythms of the cosmos.

As the Earth leans ever so slightly toward or away from the Sun, it invites us to do the same: to pause, reflect, and realign. Whether basking in the long daylight of the Summer Solstice or lighting a candle in the darkest night of winter, we participate in an ancient, shared ritual that transcends time and geography.

In this cosmic dance of light and shadow, the solstice reminds us of one essential truth: everything is in motion, yet there are moments — however brief — when we are meant to simply stand still, honor the present, and await the turning of the wheel once more.