Stoicism is an ancient Greco-Roman philosophy founded in the early 3rd century BCE that remains remarkably relevant in modern times. Far more than an abstract set of theories, Stoicism is a practical philosophy aimed at achieving a tranquil, virtuous, and resilient life. It teaches that the path to happiness lies in accepting the moment as it presents itself, using reason to understand the world, and aligning one’s will with nature.

Historical Origins of Stoicism

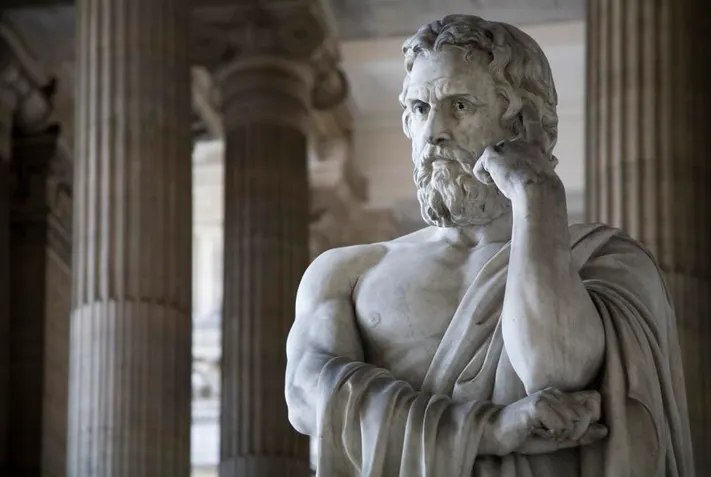

Stoicism originated in Athens around 300 BCE. Its founder, Zeno of Citium, was a Phoenician merchant who turned to philosophy after a shipwreck left him penniless. Zeno studied under various philosophical schools, including the Cynics, before founding his own school in the Stoa Poikile (Painted Porch), a colonnade in the Athenian Agora—hence the name Stoicism.

The early Stoics, including Cleanthes and Chrysippus, developed a rigorous philosophical system that covered logic, physics, and ethics. However, it was in Rome that Stoicism truly flourished, adapted by figures such as Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius.

Core Tenets of Stoic Philosophy

Stoicism is built on a few core ideas that intertwine to create a comprehensive guide to life.

1. Living in Accordance with Nature

The Stoics believed that the universe is rationally ordered and governed by logos—a divine, rational principle. To live virtuously, one must live in accordance with this natural order. Human beings, as rational creatures, fulfill their nature by exercising reason and understanding their place in the cosmos.

2. The Dichotomy of Control

One of the most famous Stoic ideas is the dichotomy of control: some things are within our power, and others are not. According to Epictetus, our thoughts, choices, and actions are within our control; external events, the actions of others, and outcomes are not. True freedom comes from focusing only on what we can control and accepting the rest with equanimity.

3. Virtue as the Highest Good

Unlike hedonistic philosophies that seek pleasure as the goal of life, Stoicism teaches that virtue is the only true good. Virtue consists of four cardinal qualities: wisdom, justice, courage, and temperance. A virtuous life is a fulfilled and flourishing life, regardless of external circumstances.

4. Control of Passions (Pathē)

The Stoics distinguished between rational emotions and pathological passions (pathē), such as excessive anger, fear, or desire. These passions arise from false judgments and ignorance. The Stoic sage aims to eliminate these destructive emotions by replacing them with rational understanding and appropriate emotional responses.

5. Practical Wisdom and Daily Practice

Stoicism is not merely theoretical. It involves daily practices such as reflection, journaling, mindfulness, and self-examination. The Stoic strives to maintain ataraxia (tranquility) and apatheia (freedom from destructive emotions), not through detachment, but through deep understanding and disciplined thought.

Major Stoic Philosophers

Zeno of Citium (c. 334–262 BCE)

Zeno laid the foundations of Stoic philosophy. Though none of his writings survive, his teachings were preserved and expanded by his students. He emphasized the unity of philosophy, asserting that logic, physics, and ethics are interconnected.

Chrysippus (c. 280–206 BCE)

Often considered the second founder of Stoicism, Chrysippus developed the logical and ethical systems of Stoicism. He wrote over 700 works and systematized Stoic doctrines. His contributions helped solidify Stoicism as a coherent philosophical school.

Seneca the Younger (c. 4 BCE–65 CE)

A Roman statesman, playwright, and advisor to Emperor Nero, Seneca brought Stoicism into the heart of political life. His writings, especially the Letters to Lucilius, offer practical advice on dealing with anger, wealth, grief, and adversity. He emphasized the importance of time and the cultivation of inner peace.

“We suffer more often in imagination than in reality.” — Seneca

Epictetus (c. 55–135 CE)

Born a slave in Hierapolis, Epictetus rose to become one of the most influential Stoic teachers. His teachings were compiled by his student Arrian in the Discourses and Enchiridion (Manual). Epictetus focused on personal responsibility, self-discipline, and the development of moral character.

“It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters.” — Epictetus

Marcus Aurelius (121–180 CE)

As Roman Emperor, Marcus Aurelius faced immense pressure and hardship. His private philosophical journal, Meditations, is a timeless classic of Stoic thought. It reflects a man striving to live virtuously amidst war, illness, and political challenges.

“You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.” — Marcus Aurelius

Stoic Ethics and Moral Philosophy

Stoicism teaches that moral virtue is sufficient for happiness. External goods—health, wealth, status—are considered indifferents. While they can be preferred indifferents (things we naturally desire), they do not contribute to our true good, which is virtue.

This view contrasts with Aristotle’s idea that external goods are necessary for flourishing. For Stoics, a poor, sick, or even dying person can still be perfectly happy—if they possess virtue and rational insight.

Logic and Physics in Stoicism

Stoics believed that logic was essential for correct reasoning, and they developed propositional logic centuries before it was rediscovered in modern times. Logic enabled the Stoic to distinguish between true and false impressions.

Their physics was deeply intertwined with theology. The Stoics were pantheists: they believed that God and Nature were identical, and that the universe is a living, rational organism. Everything happens according to divine reason or logos. Fate is the unfolding of this rational order.

The Stoic View of Fate and Providence

Stoics believed in determinism: everything happens for a reason, governed by cause and effect. However, this does not negate human freedom. Freedom lies in our response to fate. We may not control events, but we can control how we interpret and respond to them—thus aligning ourselves with the logos.

This leads to the famous Stoic attitude of amor fati—the love of one’s fate. Instead of resisting what happens, the Stoic learns to embrace it as part of the natural order.

Stoicism and the Emotions

Stoicism does not advocate for emotional suppression but for emotional transformation. Destructive emotions arise from false beliefs; for example, we grieve because we falsely believe something essential has been lost. By correcting our judgments, we can eliminate these harmful emotions.

The Stoics allowed for positive emotions based on truth—such as joy in virtue, affection for friends, or serenity in understanding.

Daily Practices in Stoicism

Stoicism is a discipline that encourages:

- Morning reflection: Preparing the mind for challenges ahead.

- Evening journaling: Reviewing actions and thoughts with honesty.

- Negative visualization (premeditatio malorum): Imagining potential misfortunes to reduce fear and increase gratitude.

- Voluntary discomfort: Practicing hardship to cultivate resilience.

- Mindfulness of the present moment: Letting go of anxiety about the past or future.

These practices help develop eudaimonia—a flourishing life grounded in virtue and peace.

Stoicism in the Modern World

The 21st century has seen a resurgence of interest in Stoicism, especially among entrepreneurs, athletes, soldiers, and individuals seeking mental clarity. Books like Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is the Way and The Daily Stoic have brought Stoic ideas to a new audience.

Modern therapies like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) are rooted in Stoic principles. The emphasis on changing one’s thinking to change one’s emotions traces back to Epictetus.

In a world marked by uncertainty, rapid change, and emotional overwhelm, Stoicism offers timeless tools: focus on what you can control, act virtuously, and accept life as it comes.

Conclusion

Stoicism is not a detached, cold doctrine but a profound guide for living a resilient, meaningful life. It challenges us to cultivate virtue, master our minds, and accept fate with grace. Its core message—that happiness lies not in what happens, but in how we respond—is as powerful today as it was in the ancient world.

From the colonnades of Athens to the courts of Rome, and now into the digital age, Stoicism endures as a philosophy of action, integrity, and inner freedom. In the words of Marcus Aurelius: “Waste no more time arguing what a good man should be. Be one.”